Directing or staging a scene is never an easy affair. You may either lack resources (actors, locations, gear, time), or you may be trying to find ways to improve it.

Either way, there are so many potential ways to fix or perfect ideas. Therefore, it is good to have a few easy to remember tools which you can refer to when your crew is pressing for instructions on how to move forward. Or when your producer requires you to nail down your choices so the budget can be finalised.

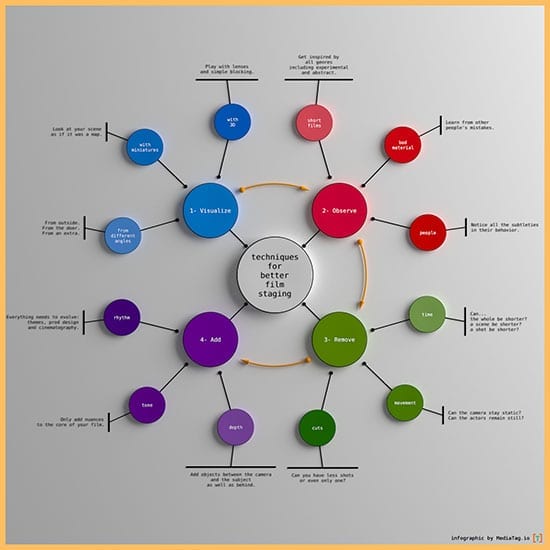

Here are 4 techniques I use regularly. Each comes with 3 different toolsets. They are meant to be used as different parts of the process, and therefore complete each other very well.

1. Visualize

Put different versions of your film in your head. Playing with those will help you find the best possible version.

Draw From Different Angles

You will surely storyboard your shoot, or at least some scenes. While you do that, try and draw scenes from angles you are almost sure not to use.

Some ideas:

- Maybe from the top, as a bird’s eye view.

- Or from the side, as if from outside the window.

- Or the door.

- Maybe from the over the shoulder of a secondary character.

Do any of those give you new ideas? Does shooting from outside the window or the door make you want to incorporate the sounds from the street? Is it lively, or is it dead silent?

Does it contrast with the interior you are currently shooting, or is it a similar atmosphere?

And that secondary character, is he or she having emotions that are not expected? Does that enrich the scene, or maybe give more depth to other characters?

Regardless what questions are raised by this process, they are always good questions. The point is to not settle on your first choice. Shuffle your ideas like you would shuffle a deck of cards. You can always come back to the first ones, and it only take a few minutes to see if this helps enriching them or not.

Storyboarding is not a rigid tool and should really be used for its full potential as a great brainstorming technique.

Use Miniature

Writing and storyboarding are the 2 main tools to prepare a scene. This will be enough in most cases, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be playful and try and find other ways to brainstorm.

Miniatures are often used for blockbusters, where teams are large and it is good to have everyone around a smaller version of the set. So it is a great communication tool.

Just like storyboarding, you can use it to research new options.

Don’t spend time building a precise version of your set or location, though. You can simply draw a map on a large sheet of paper and use sticky figures (or chess pieces, wine bottle corks, characters drawn on paper, there are many ways to keep this simple).

Then look at your characters from a high viewpoint. Do you see them taking a bit more life than they have before now? Make them play the scene and see if new ideas appear.

Previz In 3D

That might seem daunting, because 3d packages offer so much, but you will only be using a few functionalities. I personally use Houdini, which has a free version, but most will do just fine.

Just like you kept the miniature simple, only create very rough shapes. A lounge can be a cube. Maybe add another cube for the couch or table.

You should be able to find a library of characters so you can add your protagonist to the scene. But do not search for one that represents your character closely. Pick the ones that are low poly, as this will allow you to represent them loosely, just like you would with a storyboard.

And then simply add a camera and play with the framing, lenses, position of your characters.

- Do you find new angles?

- Do you spot problems with the location?

- Should it be bigger, smaller, or just different?

Again, this is about experimenting with ideas quickly and raising new questions.

2. Observe

Here are some ideas on observing:

Find Inspiration In Short Films

Feature films are a great inspiration, of course. But they can require time to watch. And it’s easy to find yourself distracted by a good film and lose track of what you were researching.

But other very enriching sources of inspiration are short films. They are often overlooked, but they are often original, and regularly push the boundaries of what has been done in other films.

Start with vimeo staff picks, and even dig into filmmakers you look up to and find all their early short films. You should also browse through the films they liked, as this is a great way to discover new filmmakers.

Bad Material

Watching great films is of course pleasurable, but it is sometimes easy to take for granted all the work that went into making them. On the other hand, when watching bad films, you may start realising how many mistakes can be easily made.

You may wonder why they edited two shots together that didn’t match. Or why that composition was so unbalanced. Or why that scene didn’t flow well. Many other questions will pop up.

Seeing those mistakes done should keep you alert, as you will take more precautions to ensure you don’t make them yourself.

People

Great filmmakers are first and foremost great observers. If you want to recreate human behavior, you need to have a deep understanding on what is natural, odd or completely artificial.

- Watch how they move.

- How they enter a space.

- Where they stop.

- How they gauge their surroundings.

- How they insert themselves into a conversation.

- How their face changes in subtle ways when they are contradicted.

- How they hide their emotions.

- Watch where their eyes go when they laugh.

People are full of subtleties. And audiences notice very quickly when characters do not behave naturally. Make sure that as a director you always have your actors’ back.

3. Remove

The best films are the ones that go straight to the point. They know what they are and what they are not. In order to achieve this, you need to remove everything that does not support your story. Here are 3 starting points.

Time

Some things to ask yourself?

- Can you make whole shorter?

- Can you make some scenes shorter?

- Can you make some shots shorter?

Actually, instead of simply asking those questions, impose this constraint on your film. If you had to make it twice shorter, what would you keep? What would be the first scene you would cut? What would be the second one? And the third?

Movement

Things to ask yourself about movement?

- Can you make the camera always static?

- Can you shoot from less angle?

- Can you suggest the monster instead of showing it?

- Can you replace a huge action sequence by off screen sound effects?

Each movement, whether it is from the camera, the cast or a vehicle, requires great care to be done convincingly. Ensure you will only have to work on the ones that are crucial to your story.

Cuts

Here’s what to consider when thinking about cuts:

- Can you do it in less shots?

- Can you merge shots in one?

- Can you do a dialogue scene in a master shot only instead of a series of singles?

Each shot is a setup, which requires specific lighting, composition work and many other small details. Merging shots may add logistical difficulties, but it can be a time saver too.

If you were to cut in all three axises, time, movement and cuts, you would end up with a photograph, a snapshot of your film.

Can you decide which one would be the best representation of your piece? You can think of it in terms of a poster, or an attention-grabbing Youtube thumbnail. But you can also think about it in terms of capturing the essence, the core of what you are trying to communicate.

It is, of course, unlikely that you will be able to share this snapshot with your audience, but this a great internal tool for you and your team. A point of reference people can go back to when they are not sure how to create a scene or frame a shot. If you are undecided between 2 shots and time is running out, this will help you make the right choice.

Or maybe you will end up with a single tracking shot, the kind that grabs the audience and keeps them hooked. Those shots also have the advantage of getting the cast and crew on their toes. But the disadvantage is that you have little margin for errors or corrections. In any case, preparation is key.

Simplify, until you can simplify no more. In order to do that, find what is the most important to your film.

It is similar to a very efficient exercise in writing, where you simplify a page into a paragraph, and a paragraph into a sentence.

Once you know what is important, you know where you spend your time and money in order to get the best possible material.

4. Add

Once you have figured out what is the bare minimum that can stay in your film, you can start expanding on it. The goal is not to add fluff, but substance. Do this with great care.

Depth

Enrich your frame. This is usually what is referred to as ‘cinematic’ look. This is not about having a filtered look. It is about composing in depth. You don’t want a character against a flat background. You want objects between the camera and your subject as well as behind it.

In most cases, the audience never notices those. It simply immerses them in your world.

In other cases, it can be used to make them feel like the protagonist does. A great example is Polanski Rosemary’s Baby, where the mother tries to hear two other characters in the adjacent room. She peaks at the door and we are just like her, we mostly see only the frame of the door, which makes us really emphasise with her.

Other very good ways to add depth is to direct the audience’s attention using negative space, shadows, depth of field, smoke or color contrast.

The tools are plentiful. Don’t use them all at once, but know them well enough to be able to use them when needed.

Tone

If you’ve thought about the snapshot your project could be summarised with in part 3 (above), this gives you your starting point for the tone.

Whether it is melancholic, sad, joyful, relentless, this will be the main one of your film. You now have to find all the subtle (or non-subtle, depending on the type of film you want to make) variations around it.

The best comedies have their dark moments, and the best horror films have comic reliefs.

But those variations always follow the same thread. The tone should never deviate from the baseline that you prepared the audience to expect from your film.

Rhythm

Music has rhythm and so should your staging. This is not something you can decide once in the edit room. Your options would then be very limited.

And just like a great song takes you on a journey, with its own internal evolution, so should your scenes.

Yet there are of course differences between those media. A song can repeat the chorus 3-4 times, and it will only get more exciting as we anticipate it. But a film that has similar scene twice will put the most caffeinated audience to sleep.

Evolution is key.

Rhythm does not have to only be variations of intensity in time. It can be subtle, like how a character changes his attitude. Decide what will change, and how those changes will unfold. Don’t always move the camera. Don’t only use close ups or only wide shots. Vary the emotion that you want to project.

Conclusion

Those were a series of tools I always use when creating new material. I apply them to the writing, preparation with cast and crew, the shoot and the post production. They are easy ways to simply challenge my own ideas, and ensure I have easy ways to look out for other solutions.

Gui Fradin is a visual effects artist (Avatar, Gravity) and filmmaker working on his first feature film, after his last short was BAFTA eligible. He also founded the creativity app for filmmakers MediaTag.io.

Matt Crawford

Related posts

4 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Great work! The camera may make the brightest of scenes appear to be it absolutely was taken during an eclipse.

Good point, cacuoc24! 🙂

Very good points. I have recently started using ShotPro to try some previsualization. It’s been very helpful, but I do think that in certain circumstances it can just bog down your workflow by adding in an extra (long) step. I prefer the Shot Designer app, though it isn’t the WYSIWYG mentality. If you can conceptualize in your head and then block from a top-down view, it is super helpful during the actual shoot.

Great comments, CS! Thanks for chiming in. Shot Designer app is awesome.

Cheers,

Matt