Ever wondered why certain movie scenes make you feel like an outsider peeking in?

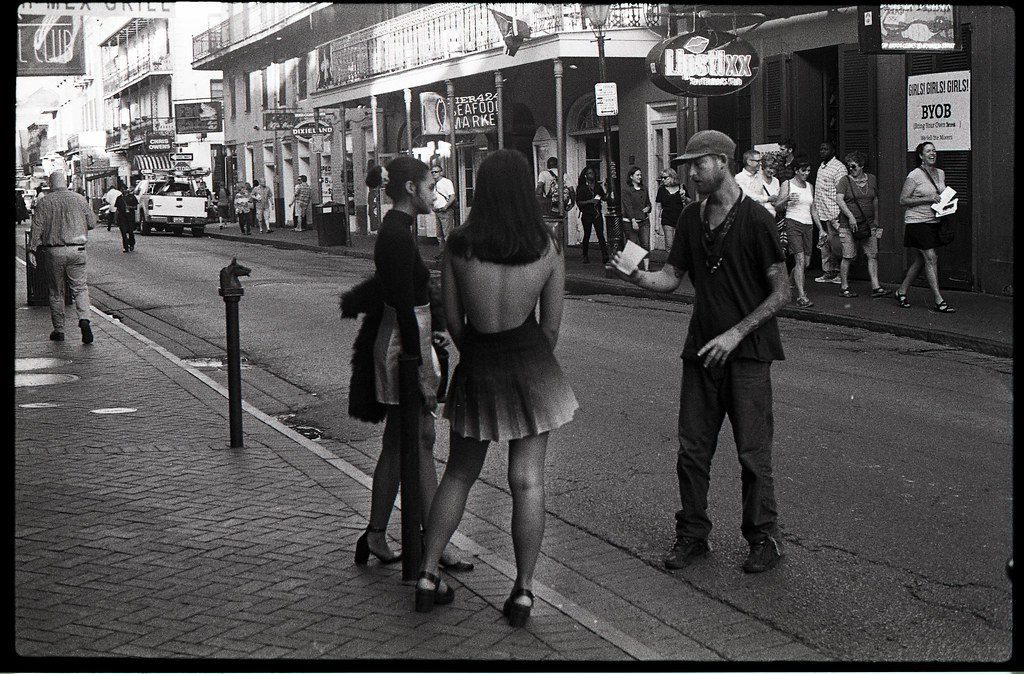

That’s often the male gaze at work, a concept that shapes how we see and are seen in visual culture.

We’ll unravel what the male gaze really means, and why it’s a critical concept in understanding media representation.

Stick with us as we dissect its influence on film, art, and beyond, and how it affects our everyday lives.

THE MALE GAZE

What Is The Male Gaze?

The concept of the “male gaze” was introduced by film theorist Laura Mulvey. It refers to the way visual arts and literature depict the world and women from a masculine point of view, presenting women as objects of male pleasure.

The theory critiques the objectification and representation of women in media and the predominance of a heterosexual, male viewpoint in film and photography.

What Is The Male Gaze?

The term “male gaze” originated with film theorist Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.

In it, she dissected the power dynamics inherent to the act of watching films, particularly through a lens that objectifies women.

Mulvey’s theory posits that mainstream cinema is structured around a masculine viewpoint, often rendering female characters as passive subjects to be viewed by the male characters and, by extension, the audience.

At its core, the male gaze arises from the imbalance of power between genders, influencing not only the portrayal of characters but also how audiences are encouraged to perceive them.

The male gaze has three distinct perspectives – that of the man behind the camera, the characters within the narrative, and the spectator in the theater or home.

Exploring the pervasive influence of this concept reveals how deeply embedded it is across cinematic history:

- Classical Hollywood cinema like Vertigo and Rear Window,

- Contemporary blockbusters and franchise films,

- Indie films seeking to subvert traditional narratives.

The prevalence of the male gaze highlights a need for greater diversity and inclusivity behind the camera.

It challenges us to reconsider the ways in which storytelling and visual presentation can evolve beyond established norms, enabling a broader spectrum of perspectives to emerge.

By acknowledging the historical context of the male gaze, we pave the way towards a more balanced and equitable cinematic landscape.

The Origins Of The Male Gaze

The concept of the male gaze was first articulated in the seminal essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema by Laura Mulvey in 1975.

It marked a pivotal moment in film theory and criticism, etching a permanent mark on how we analyze cinematic representation.

Mulvey’s essay emerged within the vibrant milieu of feminist theory and psychoanalytic critique, spotlighting the then-unspoken normativity of the male perspective in film narratives.

In identifying the male gaze, Mulvey dissected the power structures embedded in the visual language of cinema.

She contended that mainstream films are often tailored to a male spectator, with the camera’s eye aligning with a masculine point of view.

This dynamic relegated female characters to objects of visual pleasure rather than active participants in the storyline.

Considering the broader historical context:

- The studio system in Hollywood, which dominated the film industry from the 1920s to the 1960s, was predominantly male-led, with most directors, producers, and executives being men.

- These industry leaders shaped the portrayal of characters and stories, inadvertently creating and propagating a male-centric visual culture.

- The advent of feminist film theory in the 1970s, alongside other critical movements, began to challenge this orthodoxy, inspiring filmmakers and audiences to question and confront the traditional gaze.

As a result, the male gaze concept isn’t rooted solely in film but also in sociocultural and institutional practices of the time.

It became clear that to understand the male gaze, one must also examine its origins in societal norms and the historical context of the film industry.

The combined force of these elements has crafted a cinematic legacy that continues to influence the way stories are told and perceived on screen.

How Does The Male Gaze Affect Media Representation?

The male gaze influences media portrayal by often emphasizing a patriarchal perspective.

In mainstream cinema, this manifests through storylines, camera work, and character development that prioritize the male viewpoint.

- Films often feature male protagonists whose experiences and desires shape the narrative arc.

- Female characters are commonly framed through their relationships to male characters, often serving as a visual pleasure or supporting roles.

By centering male perspectives, the male gaze contributes to an unbalanced representation of gender in media.

Our understanding of male and female roles within society can be skewed by such portrayals, reinforcing traditional gender stereotypes.

The camera itself serves as a conduit for the male gaze, with cinematography and editing choices reflecting a masculine viewpoint.

Consider the lingering close-ups on women’s bodies in Transformers or the voyeuristic framing in Blue Velvet – these are classic displays of the male gaze in action.

- Visual strategies like point-of-view shots can subtly align the audience with a masculine perspective.

- Editing choices, such as cutting to a woman following a man’s gaze, further entrench the male gaze in viewing experiences.

The impact of the male gaze extends beyond film aesthetics to audience reception, shaping cultural expectations About beauty, behavior, and gender roles.

With the male gaze shaping the lens through which media is both created and consumed, it’s crucial for industry professionals and audiences to actively engage with and challenge these norms.

Conversations around the inclusion of diverse perspectives in media production are growing.

Our awareness and critique of the male gaze is a pivotal step in cultivating a more inclusive media landscape, where stories and characters resonate with a broader spectrum of experiences and identities.

The Male Gaze In Film

Cinema history is replete with examples of the male gaze shaping narratives and cinematic techniques.

In classic Hollywood, filmmakers such as Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks crafted films that often put women under the controlling eye of male characters – and by extension, the audience.

These directors employed stylistic choices that emphasized this perspective, effectively training viewers to see through a male lens.

Vertigo and The Big Sleep are quintessential films in which the male gaze is not just a visual strategy but a thematic undercurrent.

Not only do we find the lead female roles situated as objects of fascination and desire for the male protagonists, but these films also position the viewer to identify with the masculine experience.

They set the stage for understanding the dynamics of power between genders within the cinematic space.

Addressing The Male Gaze

- Awareness of the male gaze has spurred critical discussion,

- Movements towards equality in film have gained momentum.

With the growing recognition of the male gaze, there’s been a push to foster narratives that break away from this paradigm.

Films like Thelma & Louise and directors such as Agnès Varda and Jane Campion have presented stories where the female experience is neither mediated nor marginalized by male perceptions.

Their work signals an important shift towards a more balanced representation within the film industry.

The dialogue surrounding the male gaze has also opened up spaces for other perspectives – notably, the female gaze and the queer gaze.

These evolving viewpoints are central to driving forward a diverse and authentic portrayal of human experiences.

By scrutinizing the traditional gaze in this way, we’re not just redefining how stories are told, but who gets to tell them.

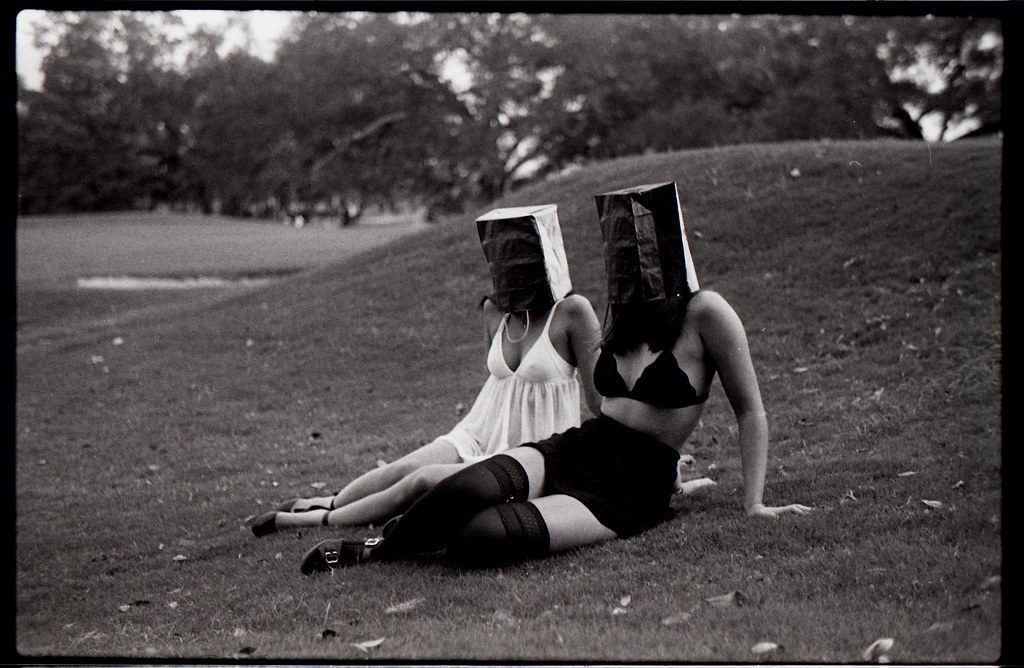

The Male Gaze In Art

When exploring the male gaze beyond the realm of film, it’s essential to acknowledge its prevalence in the wider sphere of visual arts.

From Renaissance paintings to contemporary installations, the representation of women has been informed by a predominantly male vision.

Artworks like Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus or Manet’s Olympia reveal how feminine subjects are often positioned as objects of desire for an assumed male spectator.

In modern and contemporary art, the male gaze continues to influence the depiction of female form.

Take Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Here the female figures are broken down into fragmented forms, their gaze averted, disenabling any reciprocal look upon the audience.

The fragmentation serves as a metaphor for the dissected, impartial view women are subjected to under the male gaze.

This gaze also intersects with other power dynamics including race, class, and colonialism.

Works of Western artists like Paul Gauguin exoticize and objectify the bodies of non-Western women, reinforcing the colonial gaze which goes hand in hand with the male gaze.

Consider his Tahitian series – the representation of indigenous women in these paintings speak volumes about the intersection of the exotic and erotic through the male gaze.

To critically examine these themes in art, several female artists have challenged traditional portrayals by reclaiming agency in their work.

Some notable examples include:

- Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills series – where she explores female tropes in media.

- Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece – a performance that confronts objectification by inviting the audience to cut away her clothing.

- Barbara Kruger’s collage art – which often features bold text challenging the cultural constructions of power, identity, and sexuality.

The conversation about the male gaze in art is evolving, as artists and critics alike call for broader representation and more nuanced, equitable views of gender.

By understanding these historical patterns and current dialogues, we expand the discourse and foster artistic expression that reflects a multifaceted human experience.

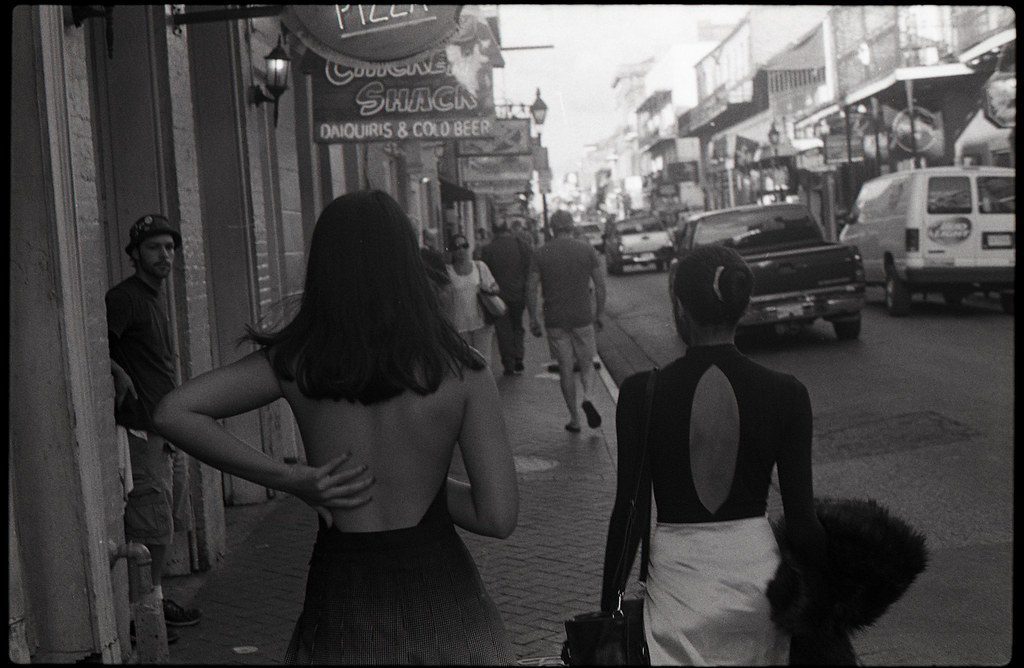

The Male Gaze In Everyday Life

Our exploration of the male gaze isn’t limited to the realms of film or visual arts, as this concept significantly permeates everyday life.

In contemporary society, the implications of the male gaze can be observed in various settings – from advertising campaigns to workplace interactions.

Advertisements often use imagery that mirrors the scopophilic pleasure found in mainstream cinema; women are frequently depicted in ways that cater to a male audience, reinforcing their objectification.

In the workspace, the male gaze surfaces through dress codes and professional expectations.

Women may feel compelled to present themselves in a manner that aligns with the male gaze, thereby affecting career progression and workplace culture.

also, social events such as weddings or nightclubs often highlight the male gaze, with expectations surrounding women’s attire and behavior showcasing the deep-seated nature of this perspective.

Addressing the male gaze in everyday life calls for a reflection upon our own behaviors and the societal norms we’ve grown accustomed to:

- Encourage inclusive dialogue that challenges stereotypical gender portrayals,

- Promote media literacy to foster awareness of the male gaze in advertising and entertainment,

- Support workplaces implementing dress code policies that prioritize comfort and equality over appearance.

It’s evident that the influence of the male gaze extends far beyond the silver screen.

It shapes social interactions and can even affect self-perception, as individuals internalize the viewer’s perspective.

To dismantle the ingrained patterns and assumptions wrought by the male gaze, we must consciously advocate for a shift toward more equitable and respectful portrayals of all genders in every facet of life.

What Is The Male Gaze – Wrap Up

We’ve seen how the male gaze has shaped our understanding of visual culture, from the silver screen to the canvas and beyond.

Recognizing its influence is the first step in moving towards a world where all genders are portrayed equitably.

It’s encouraging to witness the emergence of new narratives that challenge the status quo and embrace the female, queer, and other diverse gazes.

As we continue to push for change, we must also take personal responsibility in our daily lives to question and confront gender biases.

Together, we can foster a more inclusive society that values and represents the richness of human experience.

Let’s embrace this shift and support the creation of art and media that reflect the true diversity of our world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is The Male Gaze?

The male gaze is a concept in feminist theory that describes how visual culture tends to present women from a masculine and heterosexual perspective, emphasizing the objectification and patriarchal viewpoint in media and art.

How Does The Male Gaze Influence Media Portrayal?

The male gaze influences media portrayal by focusing on male perspectives in storytelling, cinematography, and character development, often reducing female characters to objects of visual pleasure or secondary roles.

Can You Give An Example Of The Male Gaze In Film?

An example of the male gaze in film includes classic Hollywood movies where the camera work and narrative often objectify female characters for the pleasure of the male viewer, such as the portrayal of female characters in Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

What Efforts Are Being Made To Address The Male Gaze In Media?

Efforts to address the male gaze include the production of films like “Thelma & Louise” and the work of directors like Agnès Varda and Jane Campion, who create narratives that offer alternative perspectives and challenge traditional male-centered viewpoints.

What Are Other Perspectives That Challenge The Male Gaze?

Other perspectives that challenge the male gaze include the female gaze and the queer gaze, both of which aim to depict experiences and identities in film and art from viewpoints that have traditionally been marginalized.

How Does The Male Gaze Extend Beyond Film And Into Everyday Life?

The male gaze extends into everyday life through advertising campaigns, workplace dynamics, and social events, influencing how gender roles and behaviors are perceived and dictating societal norms and expectations.

How Can We Challenge The Male Gaze In Society?

Challenging the male gaze in society involves promoting media literacy, fostering inclusive dialogues, supporting diverse representation in media and arts, and implementing supportive workplace policies to encourage equitable treatment across all genders.

Ready to learn about more Film History & Film Movements?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

9 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

The male gaze is a term used in film theory to describe the way in which male characters are typically depicted in films. The male gaze is often used to explore the ways in which male characters are viewed and interpreted by the filmmakers.

Thanks, Greg.

The male gaze is a term used in film theory to describe the way in which male characters are typically depicted in films. The male gaze typically involves the male characters looking at and objectifying female characters, often in a sexual way.

Thanks for this, Penelope.

I found this post to be incredibly insightful and thought-provoking. The concept of the male gaze has always fascinated me, and it’s interesting to learn about its historical importance and how it continues to shape our culture today. As a woman, it’s frustrating to see how women are often objectified and sexualized in media, and I believe that understanding the male gaze is crucial in challenging these attitudes and creating more inclusive and equitable representation.

Thanks for taking the time

I really appreciated this post about the male gaze, as it’s something I’ve been trying to understand better in my own analysis of media. The examples provided were helpful in illustrating how the male gaze can be perpetuated, even in seemingly innocuous situations like sitcoms. It’s important to be aware of this phenomenon and to work towards challenging it in order to create more inclusive and equitable media.

Thanks

Appreciate the comment