Many of you are fans of the Longmire TV drama series starring the Australian actor Robert Taylor as Walt Longmire, the trusty, unflappable sheriff of Absaroka County, Wyoming.

Walt takes on drug dealers, killers, and ordinary folk in this modern crime series drama with a western twist.

The series ran for six seasons, first on A&E starting in 2012 and later on Netflix. In the early days, the cinematography on the show was first-rate with well-framed shots that helped the storytelling.

Then suddenly, the style changed from a single camera setup to the use of multiple cameras.

Shots were badly framed and it was commonplace to see disconnected arms and noses. The visual style soon became very distracting for the viewer.

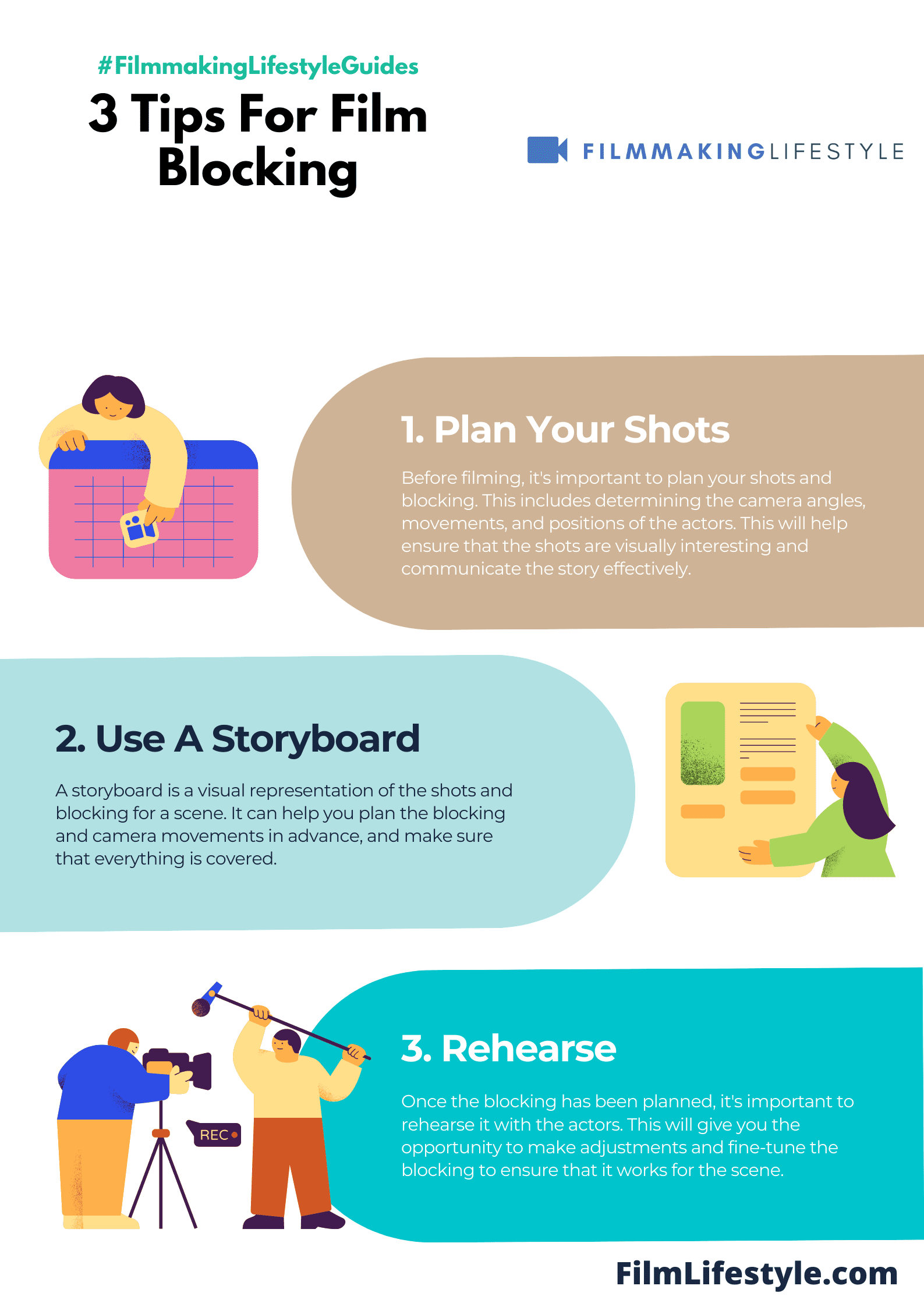

BLOCKING THE PLAN SEQUENCE

What Is Film Blocking?

Film blocking is the term that refers to the positioning of actors and props on a film set.

Film blocking is typically accomplished during pre-production, and it defines where each actor will be for every scene in the movie.

A director or cinematographer can use film blocking to create the desired effect, such as when an actor moves from one side of the screen to another.

Blocking

As a cinematographer, I have worked on numerous feature films over the years with first-time directors who had no idea how to do their blocking.

To help out, I would provide the director with blocking sketches of important scenes with actor and camera positions.

This was a time-saving mechanism because, without the sketches, we would often run late.

Blocking allows the director and continuity person to know what shots will be required in each scene and to prepare for them.

Without blocking, a film crew will often forget reverse angles and end up having to relight backgrounds to get all the pickup shots. Blocking saves time and is the key to an efficient shooting schedule.

French New Wave Changes

Back in the 1970s and 80s, the French wave-influenced large numbers of directors who swore by the “plan-séquence”: a long traveling shot of the actors moving around the set from the beginning to the end of the scene.

Long traveling shots can be great, but they take up a lot of shoot time. I have always found the plan-séquence to be very inefficient and often without interest.

Typically, they run on too long and have to be cut shorter in the editing suite.

Time is always a precious commodity on a film shoot and if a director can’t keep up with the production schedule, then the producer soon comes around calling for a meeting to discuss dropping this or that scene to save time.

It is a heartbreaking moment for any director to see their dream film come undone in this way.

As a director and cinematographer, my priority has always been coverage, that is getting all the shots I need to create a seamless edit.

A relatively simple scene might require some twenty-five shots and five different camera positions to cover all the angles. The sketches allow the camera and lighting crew to move quickly and logically from setup to setup.

A Well Thought Out Plan

With a well-thought-out plan, you can better control the dramatic tension by using all the tools at your disposition from wide shots to medium shots and close-ups in an orderly progression.

Blocking forces one to decide how a scene opens and closes, and helps everyone visualize how the final edit will come together.

The plan-séquence may be great for opening scenes but it should not be used too often.

Why?

Not all scenes are created equal in any given screenplay.

I firmly believe that most scripts have only three or four really important scenes – the lifeblood of the story – that will require special attention, while the rest of the script is composed of story filler and establishing shots.

These are scenes that really capture the imagination of the public and make for the success of the movie. Actors prep for these scenes before the production of a movie begins.

Directors need to reserve time for these scenes and hurry through the filler and establishing shots, shooting them as quickly as possible.

So if your actor steps out of a car and then enters a building, you don’t want to be doing a long crane shot of the location when all you really need is a five-second clip of the action.

People won’t remember the establishing shots in your movie, but they will remember the important scenes if they are done right. It is these scenes that will make or break your film for the viewing public.

Furthermore, directors who show that they are sensitive to the needs of their actors by prioritizing the important scenes in a film, obviously get better performances. There is less stress on the set when everyone is working towards a common goal.

The actors are calmer, knowing that time has been allocated to allow multiple takes and they will not be rushed through a scene.

It is this kind of clarity of vision that helps create great films from the chaos of the movie set.

The Twenty-minute Rule

Now a brief word about editing and pacing. A rule of thumb that was drummed into me as a young director is the twenty-minute rule.

I had just finished the first cut on a very personal project of mine, a feature movie shot in Eastern Europe, and was screening it with the distributor on an old Steenbeck editing table in Montreal.

The distributor soon became bored and felt the pacing of the film was progressing too slowly.

He was going to release the picture in several cinemas in Montreal and Toronto and wanted me to cut two scenes in the first reel (twenty minutes).

I objected because, without those scenes, there would have been nothing to justify the character’s actions in the scenes that followed.

It seemed to me to be a highly subjective call and no one else expressed a similar opinion in the screening room.

Would cutting three minutes out of the first reel really increase viewer interest in the movie? I was not convinced and refused to make the cuts.

I learned later that distributors often use this kind of complaint as a way of deflecting blame when a film fails at the box office.

The director and producer are to blame, not the distributor who screws up the cinema release. In my case, the distributor used the complaint against me to avoid paying the full amount for the rights to the film.

The lesson to be learned here is that the film industry is full of complete idiots and you should never trust a comment from someone you don’t know well.

Yes, distributors, producers, and even script readers are often incompetent, that’s a fact. Think for a moment about Harvey Weinstein, the successful Miramax producer, and convicted sex offender.

If Harvey told you to cut several scenes in your movie, would you believe it? No, of course, you wouldn’t.

You would definitely consult a trusted industry professional to get their opinion and then make up your mind. Success in the film industry is not a guarantee of competence.

I remain a strong believer in the twenty-minute rule even after the incident described above. In television drama today, you no longer have twenty minutes to hook the audience.

It is more like five or ten minutes at the most. The rule remains useful when reading scripts. If you still don’t know where a story is going after reading fifty pages, you know the script is dead on arrival and will never go anywhere.

The same rule applies in novels. The story has to hook the reader within the first twenty pages. In the film industry, directors do tend to fall in love with their favorite scenes in a movie.

It’s often because the scene in question required enormous effort to film and was beautifully done, but it doesn’t mean that the scene should be awarded five minutes of screen time. If it isn’t working, then it might be better to simply cut the scene from the picture or reduce its length.

Another trap that a lot of filmmakers fall into is “cool shot” mania. In a scripted, narrative film, technological prowess will not save your film.

It might save a dull corporate video from rejection, but it won’t advance the storytelling on a feature-length drama show. Just about anybody with a camera these days has the capacity to shoot in 4K and the technological advances are amazing.

The corner store filmmaker has a drone, a gimbal stabilizer, a slider, LUTs, marvelous editing software, color correction, and noise reduction that would have seemed impossible several years ago.

The problem may be that there is too much technology available today and most people don’t know how to use it effectively.

Shallow Depth-of-field

Today, we have the shallow depth-of-field fad where everything is shot at F/1.2. Eyes may be in focus, but noses are not. In the old days, shallow depth-of-field was a tool to direct focus to a face or a detail in the image.

I remember as a cameraman struggling to get sufficient depth of field for a two-shot of actors sitting side by side in a car. We pushed this to the limit using the depth-of-field tables in my copy of American Cinematographer.

We changed lenses going for wider angles, boosted the light source, or stopped down underexposing the film so that our image would be sharp on both faces simultaneously.

Today, no one worries anymore about trying to keep both faces in focus and you’ll often see entire scenes where one of the characters is out of focus. These are stylistic changes but they do show a lack of sensitivity to film storytelling.

Remember Alec Guiness in the role of George Smiley in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (the 1979 version) where he sits in a beat-up car with Jim Prideaux, the broken MI6 agent, played by Ian Bannen, two damaged souls in a John le Carré film.

The two characters sit side by side in sharp focus in that car, at peace with the world or in an angry confrontation.

The two-shot can be a great cinematic tool when it is done right. There is nothing natural in a two-shot when one of the characters facing the camera is out of focus for most of the scene. Of course, today, many directors like to use out-of-focus shots as transition scenes which are very effective.

Cinema Fads

Another annoying cinema fad is the shaky cam that has been used for years to give a documentary feel to the cinematography.

It is used in violent action films for dramatic effect and can be quite effective when used sparingly.

It started back in 1993 with NYPD Blue and ER but I find its use on more recent television shows like Blindspot particularly annoying.

The series is difficult to watch and very distracting since you are constantly aware that a mentally ill person is holding the camera and is about to pass out.

Today, I think the shaky cam has run its course and it won’t be used very often in such an obvious way.

Other faddish cinematic effects that can take away from your story include time-lapse and slow-motion effects. Used sparingly, they can work their magic, but one has to be very careful not to overdo it.

Having worked a long time in independent film, I regret to say that many festivals will reject a film if there are too many creative cinematic effects in your movie.

Big Hollywood movies may love the creative impulses of their highly paid directors, but you will not be a star in independent films where the simplicity of expression is the only rule for success.

Festival screeners abhor anything other than fixed shots and are likely to go into cardiac arrest if they see a slow-motion or a time-lapse effect sneak its way into the movie.

Nicholas Kinsey is a Canadian / British director and cinematographer of feature films and television drama.

He has been a successful director, scriptwriter, director of photography, film editor, and producer over a long career.

Nicholas has directed and photographed eight feature movies in 35mm and written some twenty feature and television drama screenplays.

He is owner and producer at Cinegrafica Films in Quebec, Canada since 2014 and writes a history blog. See his credits on IMDB.