Nollywood stands as the vibrant heartbeat of African cinema, a film industry bursting with creativity and drama.

It’s the world’s second-largest movie industry by volume, right after Bollywood, producing thousands of films annually.

We’ll explore how Nollywood has become a cultural phenomenon, transcending borders and captivating audiences worldwide.

Get ready to jump into the colorful world of Nigerian cinema, where stories come alive in the most unexpected ways.

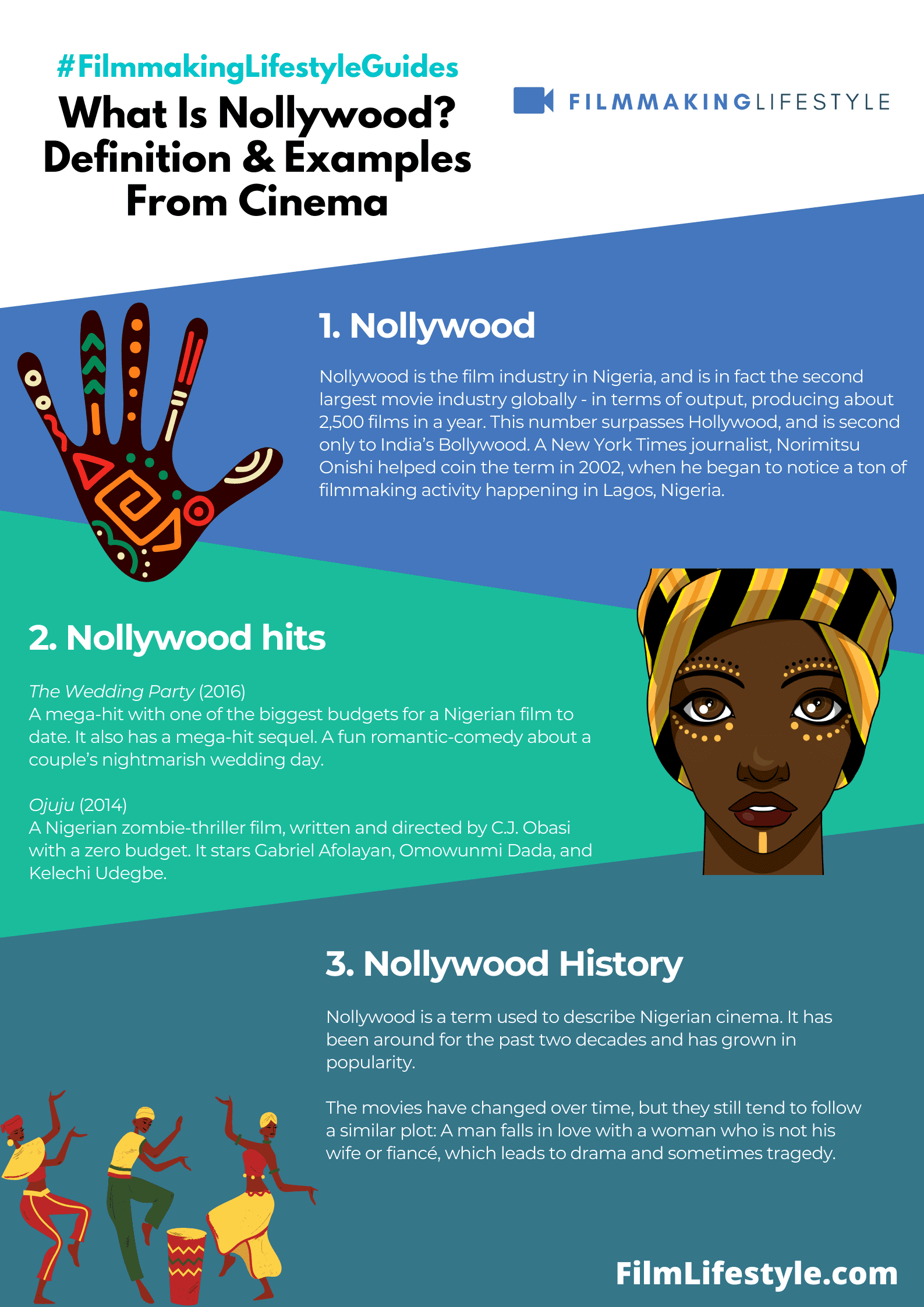

WHAT IS NOLLYWOOD

What Is Nollywood?

Nollywood refers to the Nigerian film industry, one of the largest film producers in the world by volume. Originating in the early 1990s, Nollywood films are known for their prolific output, with thousands of titles released annually.

These films are typically low-budget, and often shot and produced within a matter of weeks. Nollywood covers a wide range of genres, with a strong emphasis on drama, romance, and comedy, often infused with African cultural elements.

Despite technical limitations, Nollywood has a significant cultural impact in Africa and among the African diaspora, providing a platform for African narratives and storytelling.

History Of Nollywood

The origins of Nollywood trace back to the late 19th century when the first films were introduced to Nigeria by colonial traders.

Initially, these were foreign movies, but it wasn’t long before Nigerians began telling their own stories.

The 1960s and 1970s marked the emergence of Nigerian cinema with films like Kongi’s Harvest and Things Fall Apart which were adaptations of African literary works.

This period set the stage for what would become a flourishing industry.

In the early 1990s, Nollywood took a definitive shape with the release of Living in Bondage.

This movie, produced by Kenneth Nnebue, was shot straight to video due to the high cost of film production and limited number of cinemas.

It sold over a million copies, signifying an untapped market for local stories told by local voices.

The growth of Nollywood can be attributed to several factors:

- Technological advancements – the digital revolution made filmmaking more accessible.

- Market demand – there is a strong desire among Nigerians and the African diaspora for stories that reflect their experiences.

- Entrepreneurial spirit – filmmakers are often self-taught, using creative means to produce and distribute films.

As Nollywood matured, diverse genres emerged, catering to the tastes of a wide audience.

Drama, comedy, and supernatural themes are prevalent, while recent years have seen a rise in action and romance.

plus to theme proliferation, there has been a growing emphasis on quality, with better production values and storytelling sophistication.

Today, Nollywood’s influence extends beyond Africa, as its films are screened at international festivals and distributed globally.

The industry serves as a powerful medium for cultural expression, employment, and is a testament to the ingenuity of Nigerian filmmakers who have turned constraints into triumphs.

Growth Of The Nigerian Film Industry

The Nigerian film industry, commonly known as Nollywood, has witnessed exponential growth since the early 1990s.

The release of Living in Bondage paved the way for a booming video film era.

This period marked not only a shift in the consumption of films but also in their production – filmmakers discovered that straight-to-video releases were a more viable financial model given the economic climate and the difficulties of securing cinema distribution.

The advancements in digital technology have further propelled the industry forward.

Utilizing affordable digital equipment –

- video cameras,

- editing software,

- online platforms for distribution Nigerian filmmakers have been able to slash production costs and timelines. This democratization of the filmmaking process has permitted a staggering output of films annually, making Nollywood the world’s second-largest film industry in terms of the number of productions.

Genres in Nollywood are as diverse as the narratives they portray.

From drama to comedy and action to romance, they reflect the complexities and dynamics of Nigerian society.

Traditional themes often mesh with modern-day stories, creating a rich tapestry that resonates with a broad audience.

Exporting culture globally has been one of Nollywood’s most significant achievements.

Its films are enjoyed across the African continent and beyond, forging connections through shared cultural experiences and creating an international appetite for African stories.

As the industry continues to grow, it seeks new markets, finding fans in unexpected places and platforms.

With every film release, Nollywood enhances its mechanisms for generating revenue.

Through international film festivals and various streaming services, Nigerian filmmakers find avenues to showcase their creativity and expand their reach.

This strategy not only cultivates a wider audience but also attracts foreign investment and partnerships, which are crucial for the industry’s sustainability and growth.

Engagement with other film industries has nurtured co-productions and training exchanges.

Collaborations with international filmmakers bring fresh perspectives while offering training opportunities that elevate the technical and storytelling prowess of Nollywood’s creators.

This synergy is essential for the evolution of the industry, maintaining its cultural essence while expanding its professional networks and reputation on the global stage.

Best Nollywood Movies

Here’s a list of some best Nigerian films ever made.

Lionheart (2018)

Lionheart (2018) is a Nigerian Nollywood film directed by Timothy Ekundayo Adeola, starring Nigeria’s finest actors and actresses.

The movie tells the story of an 11 year old girl (Amina) with supernatural powers who loses her father to assassins while trying to save him.

The movie also stars Bimbo Akintola, Seun Akindele, Okey Uzoeshi, Kayode Olaiya, Ngozi Ezeonu and more. The film was premiered on October 20, 2018 at the Genesis Deluxe Cinema, Festac Town in Lagos State.

Lionheart is a journey into one family’s search for healing after their son was murdered by drug dealers.

The film addresses the anger that often accompanies and fuels violence in many communities around the world.

Lionheart intends to inspire young people to have courage and do what is right rather than what is easy or popular.

- Jean-Claude Van Damme, Ashley Johnson, Brian Thompson (Actors)

- Sheldon Lettich (Director)

- Audience Rating: R (Restricted)

Chief Daddy (2018)

Chief Daddy is a 2018 Nigerian comedy-drama film, produced by EbonyLife Films and directed by Niyi Akinmolayan.

It stars Funke Akindele, Patience Ozokwor, Ini Edo, Joke Silva, Kate Henshaw and Richard Mofe Damijo.

The film follows the story of billionaire industrialist “Chief” Beecroft, a flamboyant benefactor to a large extended family of relatives, household staff and mistresses.

After his unexpected death, his outrageous will becomes public knowledge which sets off a frenzy of hijinks from the immediate family members all jostling for their share of the inheritance.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, Adrienne Corri (Actors)

- Stanley Kubrick (Director) - Stanley Kubrick (Writer) - Stanley Kubrick (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

The Wedding Party 2 (2016)

When the sequel to the critically acclaimed film The Wedding Party (2015) was announced, all of Nigeria and Ghana went crazy with excitement.

Fans couldn’t wait to see what happened next in this hilarious tale of a wedding gone wrong.

A great way to get the most out of viewing The Wedding Party 2 is by having some knowledge about Nigerian culture.

For this reason, I have put together a list of things you should know before watching the movie that will give you a better understanding of what’s happening in the film.

In Nigeria, it is common for people to refer to one another using kinship terms like “Uncle” and “Auntie.”

This means that when someone calls themselves your Uncle or Auntie they might actually be an older friend or acquaintance instead of a blood relative.

- Nia Vardalos (Actor)

- Kirk Jones (Director)

- French, Spanish (Subtitles)

- Audience Rating: PG-13 (Parents Strongly Cautioned)

Lost In London (2017)

Lost In London (2017) nollywood film Lost In London is a 2017 Nigerian comedy drama film produced and directed by Moses Inwang.

It was shot in London, the United Kingdom. It features an ensemble cast of Nollywood actors including Ramsey Nouah, Alex Ekubo, Blossom Chukwujekwu, William Benson, Wale Ojo, Uche Jombo, Sambasa Nzeribe, Iretiola Doyle, Tina Mba and Toyin Aimakhu (now Toyin Abraham).

It was premiered at Filmhouse Cinema Surulere on 5 March 2017. It has also been screened at Pan African Film Festival in Los Angeles on 14 February 2017 and at George Washington University in Washington DC on 18 February 2017.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, Adrienne Corri (Actors)

- Stanley Kubrick (Director) - Stanley Kubrick (Writer) - Stanley Kubrick (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Love Is War (2019)

Rita Dominic and OC Ukeje star in the newly released Nollywood movie titled Love Is War Love Is War is a 2019 Nigerian romantic comedy film directed by Omoni Oboli.

The film stars RMD and OC Ukeje. It was released on October 25, 2019 The film’s plot chronicles the love story of two people (Rita Dominic, OC Ukeje) who fall in love in their late twenties.

They are both accomplished professionals who are career-driven and doing very well in their respective careers. Their lives are perfect but they both desire to get married and start a family.

As they pursue their desire to find true love, they have to work through the challenges of falling in love with the right person at the wrong time. It’s a story about love, dedication, selflessness, marriage, business ethics, and parenthood.

- English (Subtitle)

- UK-LASGO (Publisher)

The Figurine (2009)

Based on a true story, the film tells the tale of a young British woman who travels to Nigeria in search of an African artefact rumoured to possess the power of life and death.

The only problem is that she gets more than she bargained for when she unwittingly unleashes an ancient evil. Tensions rise as a series of mysterious deaths surround her.

It is then that her brother and sister-in-law join forces with local Nigerian police officers to unravel the mystery behind the figurine.

The cast includes: Sola Asedeko, Tope Tedela, Mary Lazarus, Okey Uzoeshi, Bimbo Manuel, Desmond Elliot, Yomi Fash Lanso, Ayo Mogaji, Paul Utomi and Mary Remmy Njoku.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Malcolm McDowell, Patrick Magee, Adrienne Corri (Actors)

- Stanley Kubrick (Director) - Stanley Kubrick (Writer) - Stanley Kubrick (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Impact Of Nollywood On Nigerian Culture

Nollywood has firmly rooted itself in the cultural landscape of Nigeria.

Ours is a film industry that does more than tell stories – it shapes identities and reflects the complexity of everyday life.

Whether through heart-wrenching dramas or rib-tickling comedies, Nollywood captures the essence of Nigerian resilience and ingenuity.

It’s no overstatement to say that Nollywood serves as a mirror, showcasing traditional customs and contemporary challenges alike.

The films often blend these elements, influencing fashion trends and colloquial speech, thereby reinforcing cultural norms and sparking new conversations.

Here are a few areas where Nollywood’s impact is most pronounced:

- Language and Slang – Nollywood has popularized Nigerian Pidgin and various ethnic languages, integrating them into the global lexicon.

- Fashion and Style – Traditional attire featured in films has seen a resurgence in everyday wear, highlighting Nigerian designers.

- Music and Dance – Film soundtracks have contributed significantly to the dissemination and popularity of Afrobeat and local music genres.

By bringing Nigerian stories to a global audience, Nollywood has become an essential vehicle for cultural diplomacy.

Our films are often a first point of contact with Nigerian culture for international viewers.

They have the power to correct misconceptions and provide more nuanced understandings of our nation’s complexities.

Future projects show Nollywood’s potential for continued cultural advocacy.

With every film, we initiate crucial dialogues on societal issues, from governance to gender roles.

Nollywood has proved it’s far more than entertainment – it’s a cultural force that influences and inspires, and with the rise of digital platforms, its reach keeps extending.

Nollywood’s Influence Globally

The reach of Nollywood stretches far beyond the borders of Nigeria or even Africa.

As a cultural product, Nollywood films have found audiences across the globe, providing an alternative to Hollywood and Bollywood narratives.

They shine by showcasing universal themes through a distinctly Nigerian lens, offering insight into the country’s complex society, elaborate traditions, and spirited communities.

International film festivals have become pivotal platforms for Nollywood films, earning them critical acclaim and awards that boost their profile.

For instance, Half of a Yellow Sun and The Figurine garnered international recognition, demonstrating the industry’s capacity to produce quality work that resonates with global audiences.

Festivals also serve as networking hubs, connecting Nigerian filmmakers with international producers and distributors.

Here are some key reasons for Nollywood’s rising global influence –

- Compelling storytelling that resonates with diaspora communities worldwide.

- Strategic use of digital platforms for wider distribution.

- Collaborations with international actors and directors that bridge cultural gaps.

Online streaming services have also played a significant role in catapulting Nollywood onto the world stage.

Giants like Netflix have invested in original Nollywood content, thereby amplifying its reach and embedding Nigerian stories in the fabric of global entertainment.

Interactive subtitles and dubbing options break down language barriers and make the films accessible to an even broader audience.

As our fascination with global cinema grows, we continue to explore filmmaking movements from around the world.

Nollywood’s ascent on the international scene is a testament to the industry’s versatility, creativity, and the universal appeal of its narratives.

This success not only elevates African cinema but also enriches the global film landscape, proving that compelling stories can transcend borders and language barriers.

Challenges Faced By Nollywood

While Nollywood has seen remarkable growth, several challenges continue to impede its progress.

Piracy is one of the largest concerns – it hampers profitability and discourages potential investments in the industry.

Our filmmakers are often at a disadvantage as their earnings are severely undercut by the rampant illegal distribution of their work.

The quality of production has often been criticized.

Due to budget constraints and a push for quick turnarounds, many Nollywood films suffer from poor production values, which can detract from their global competitiveness.

This includes aspects such as:

- Inadequate lighting,

- Subpar sound design,

- Limited post-production capabilities.

Access to funding remains a significant hurdle.

Unlike Hollywood, with its vast array of financial backing, Nollywood struggles to secure the necessary funds to elevate production quality and afford better equipment, seasoned actors, and more experienced directors.

Distribution and reach pose another set of challenges.

Even though online streaming platforms have opened new avenues, many Nollywood films still struggle to get the kind of international distribution that could catapult them onto the global stage.

finally, infrastructural deficits such as unreliable electricity, limited internet penetration in some regions, and a scarcity of modern filming facilities can stifle the creative process and delay production schedules.

Our filmmakers are often forced to innovate beyond these limitations to bring their visions to life.

Even though these challenges, Nollywood’s tenacity and resourcefulness continue to drive the industry forward, reshaping perceptions and breaking boundaries in the cinematic world.

What Is Nollywood – Wrapping Up

We’ve seen Nollywood’s resilience in the face of various obstacles that would stifle a less determined industry.

Our exploration has shed light on the issues that persist yet also highlighted the industry’s relentless push for excellence.

As Nollywood continues to innovate and captivate audiences worldwide we’re reminded of the power of storytelling and the universal appeal of film.

With each challenge comes an opportunity for growth and Nollywood is a testament to the enduring spirit of creativity.

Let’s watch expectantly as this dynamic industry evolves promising to deliver even more compelling stories to the global stage.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are The Main Challenges Facing Nollywood?

Nollywood struggles with issues like rampant piracy, subpar production quality, scarce funding, distribution barriers, and insufficient infrastructure which all impede its progress and profitability.

How Does Piracy Affect Nollywood?

Piracy severely undermines the revenue of Nollywood films, as illegal copies are distributed and sold without compensation to the creators, leading to significant financial losses.

Are The Production Qualities Of Nollywood Movies Improving?

While there has been some improvement, Nollywood still faces challenges in achieving consistently high production quality due to limited budgets and technical resources.

What Issues Does Nollywood Have With Funding?

Nollywood filmmakers often encounter difficulty accessing finance, with limited investment and sponsorship opportunities, making it challenging to scale up production values and marketing efforts.

How Does Nollywood Manage Distribution And Reach?

Distribution remains a challenge, with Nollywood depending on a mix of traditional markets, informal networks, and emerging digital platforms to reach audiences, often with limited formal distribution channels.

What Kind Of Infrastructural Deficits Affect Nollywood?

Nollywood faces infrastructural challenges such as insufficient state-of-the-art filming equipment, inadequate professional training facilities, and a lack of dedicated spaces for production and screenings.

Ready to learn about more Film History & Film Movements?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

4 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

![Lionheart (2-Disc Special Edition) [Blu-ray + DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51NqzvzxS3L.jpg)

![My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2 [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51OBJodVI+L.jpg)

![Fifty Shades of Grey: The Unseen Edition [Blu-ray] [2015]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Kt15wMV4L.jpg)

Nollywood is a Nigerian film industry. It is the most popular film industry in Africa and the seventh most popular in the world.

Thanks, Mitchell.

Interesting read! I had no idea Nollywood was the second-largest film industry in the world by volume. Learned a lot about its history and impact on African cinema. Looking forward to exploring more of your blog posts!

Thank you