Land art is a form of art that involves the use of the earth as its primary medium. The term “land art” was coined by the American artist Robert Smithson in the late 1960s, and it is used to describe any work that involves one or more pieces of land.

Land artists also make use of natural materials such as soil and water, and they may include objects such as rocks, trees, or even animals.

Land art can be in any form, including sculpture, painting, photography, video installation and performance art.

It can be highly conceptual or purely abstract, but it does tend to use some aspect of nature as its main focus.

What Is Land Art

What Is Land Art?

Land art is a form of art that takes place on or near a physical landscape, usually in public places but sometimes in private, to create works that are temporary and ephemeral.

Land art typically features natural elements such as plants, animals, rocks, and weather.

The term “land art” was coined by American artist Joseph Kosuth in 1967. It is related to the concept of land sculpture, which means “sculpture made out of the earth by digging or carving.”

Land art transforms the natural landscape into an artistic canvas, challenging our perceptions of art and environment.

It’s an earthy fusion where the great outdoors meets creative expression, often on a monumental scale.

We’ll jump into the origins of this movement, its key figures, and how it’s evolved over the decades.

Stay tuned as we explore the synergy between art and the earth, revealing how land art has made its indelible mark on both the art world and the planet itself.

Origins Of Land Art

Land art emerged during the late 1960s and early 1970s, primarily in the United States, as a radical departure from the confines of traditional gallery spaces.

This movement sought to situate art within the vastness of nature, encompassing everything from soil to rock formations.

It was a part of a larger conceptual art movement that gravitated towards the dematerialization of the art object.

The pioneers of land art were motivated by a desire to create works that were inextricably linked to their environment.

Their creations often required the viewer to travel to remote locations, engaging with the art on a physical level.

Some notable figures in the movement include:

- Robert Smithson, known for his monumental earthwork Spiral Jetty,

- Michael Heizer, whose Double Negative involves massive incisions into the desert terrain,

- Walter De Maria, with works like The Lightning Field.

These artists, among others, forged a new language in the artistic dialogue, one that spoke to the impermanence of art and its symbiosis with our planet.

With their earthworks, they encapsulated a moment in time, far beyond the traditional permanence sought in paintings and sculptures.

We’ll explore more about how these land artists manipulated the earth in ways that were as innovative as they were imposing, using the natural canvas to reflect both environmental concerns and philosophical inquiries.

These endeavors bridged the gap between art and environmental activism, making a bold statement about human interaction with nature and the fleeting nature of our existence compared to the enduring life of the earth.

Key Figures In Land Art

As we jump deeper into the essence of land art, it’s crucial to highlight the visionaries whose groundbreaking work cemented the movement’s place in art history.

Their creations not only redefined the boundaries of art but also challenged the way we perceive the natural landscape around us.

Robert Smithson is perhaps most renowned for Spiral Jetty, a colossal earthwork that spirals into the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

Smithson’s work embodies the core principles of land art – integrating art seamlessly with the environment and emphasizing the transient nature of both.

Michael Heizer continued to push the scales with works like Double Negative, which saw him literally cut through the Nevada desert, leaving behind a monumental intervention that can only be fully appreciated from a distance.

Heizer’s pieces often require an aerial view, aligning the art form with the broader context of landscape photography and film.

Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field in New Mexico is a testament to the fusion of land art with natural elements.

His work encourages visitors to experience the synergy between the earth and sky, especially during thunderstorms where the titular lightning dramatically interacts with the installed poles.

Notable contributions to the land art movement also include:

- Nancy Holt – known for her work Sun Tunnels, which frames the sky in a remote Utah desert, offering an immersive perspective on the cosmos.

- Andy Goldsworthy – acclaimed for his transient works using natural materials, Goldsworthy’s art poignantly illustrates the ephemeral nature of existence.

Our appreciation for these artists’ contributions to the field of land art is profound.

Their work perpetually inspires us to see the earth through a lens of imagination and boundless possibility, uniting creativity with the raw aesthetics of nature.

Monumental Scale Of Land Art

The gravity-defying scope of land art is an essential hallmark of this movement, often blurring the boundaries between art, architecture, and environmental activism.

Iconic works like Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson not only showcase art’s potential to engage with a vast canvas but also how these creations evolve over time due to natural elements.

In Double Negative, Michael Heizer manipulated the landscape on a massive scale, shaping not just the physical space but our perceptions of void and presence.

This enormity compels us to consider our own place within the environment and the marks we leave behind.

Such works are powerful reminders of both human ingenuity and the sublime forces of nature that can overwhelm it.

- Land art challenges our understanding of permanence,

- The large-scale works encourage a dialogue with the viewer’s surroundings,

- These pieces emphasize our small but significant role within a larger ecological context.

Integrating land art within the filmmaking narrative has forged a new path for visual storytelling.

Captured through the lens, these vast creations transform in meaning, allowing audiences to experience both the intimacy of detail and the overarching grandeur from perspectives only film can provide.

With Walter De Maria’s Lightning Field, the artwork is not just about the static visual appeal; it’s an immersive experience that involves the changing light, the weather patterns, and the passage of time—elements that resonate profoundly with the cinematic exploration of ephemeral moments and moods.

This interplay between the artwork and its environment underlines the impermanence of the art itself and its perception.

The Synergy Between Art And The Earth

Land art offers an intersection where the pastiche of nature and human ingenuity fuse to birth a profound narrative.

These works are not merely placed in the environment; they are conversations between the material of the earth and the artist’s hand.

The synergy is evident in Michael Heizer’s Double Negative.

Here, the colossal incisions into the earth’s crust epitomize humans’ capacity to alter landscapes while also paying homage to the raw forms that predate our existence.

Our role in this dialogue extends beyond passive observation.

Through these interactions, we’re invited to question the essence of our relationship with the natural world, to reconsider our place within it, and to ponder the potential harmonies and frictions.

- Engaging with earthworks evokes a myriad of reflections: – The impermanence of our creations amidst enduring geological timescales. – The contrasts between industrial human activity and nature’s organic processes. – The transformative impact of weather and time on static art forms.

In embracing the unpredictable elements of wind, erosion, and flora, land artists remind us that control is an illusion.

Pieces like Spiral Jetty by Robert Smithson undergo a continuous evolution, shaped by the living environment that cradles them.

Land art embodies a powerful paradox – monumental permanence versus the ephemerality of experience.

By extrapolating cinema techniques and storyboarding vistas, we frame these artworks in a manner that captures their enduring narrative while acknowledging their temporal fragility.

Land Art’s Impact On The Art World And The Planet

Land art undeniably expanded the canvas for artists, freeing them from the constraints of galleries and traditional exhibition spaces.

Our relationship with artworks such as Spiral Jetty or Double Negative surpasses mere visual appreciation – it demands physical interaction and inspires environmental contemplation.

Through land art, we’ve seen a profound engagement with ecological issues and the human impact on nature.

Artists like Andy Goldsworthy use materials such as ice, stone, and leaves, highlighting the transient beauty of the natural world and our fleeting role within it.

The movement has also altered the approach of museums and galleries towards art preservation and exhibition:

- Museums now often include Earthworks documentation as a vital aspect of their collections.

- They’ve fostered collaborations with filmmakers and photographers to capture the essence of these ephemeral pieces.

- Conservation strategies have broadened, considering not only the artwork itself but also its surrounding environment.

In the broader cultural context, land art challenges us to rethink our role on Earth and our legacy.

Its impact is as monumental as the works themselves, reflecting back to us both the impermanence of human endeavors and the vastness of geological time scales.

Land art has carved a niche in cultural and environmental discourse, proving that art’s power to influence extends far beyond the confines of traditional spaces.

Films like Rivers and Tides exquisitely portray the poetry and process of creating art with the natural world as both medium and message.

It’s clear that the ripples of land art are still expanding, inspiring contemporary artists and the public to embrace a more mindful and holistic approach to the intersection of art and environment.

This movement is not just about the alteration of landscapes but a transformation in how we perceive our place in the ecosystem – an artistic revelation that resonates through every soil-caked sculpture and windswept installation.

What Is Land Art – Wrap Up

Land art has reshaped our interaction with the environment and art itself.

We’ve seen how it transcends traditional boundaries and invites us to engage with the planet in a profound way.

As we reflect on the movement’s impact, we’re reminded of the delicate balance between human expression and Earth’s enduring grandeur.

Let’s carry forward the spirit of land art, allowing it to inspire our creative journeys and inform our stewardship of the natural world.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Land Art?

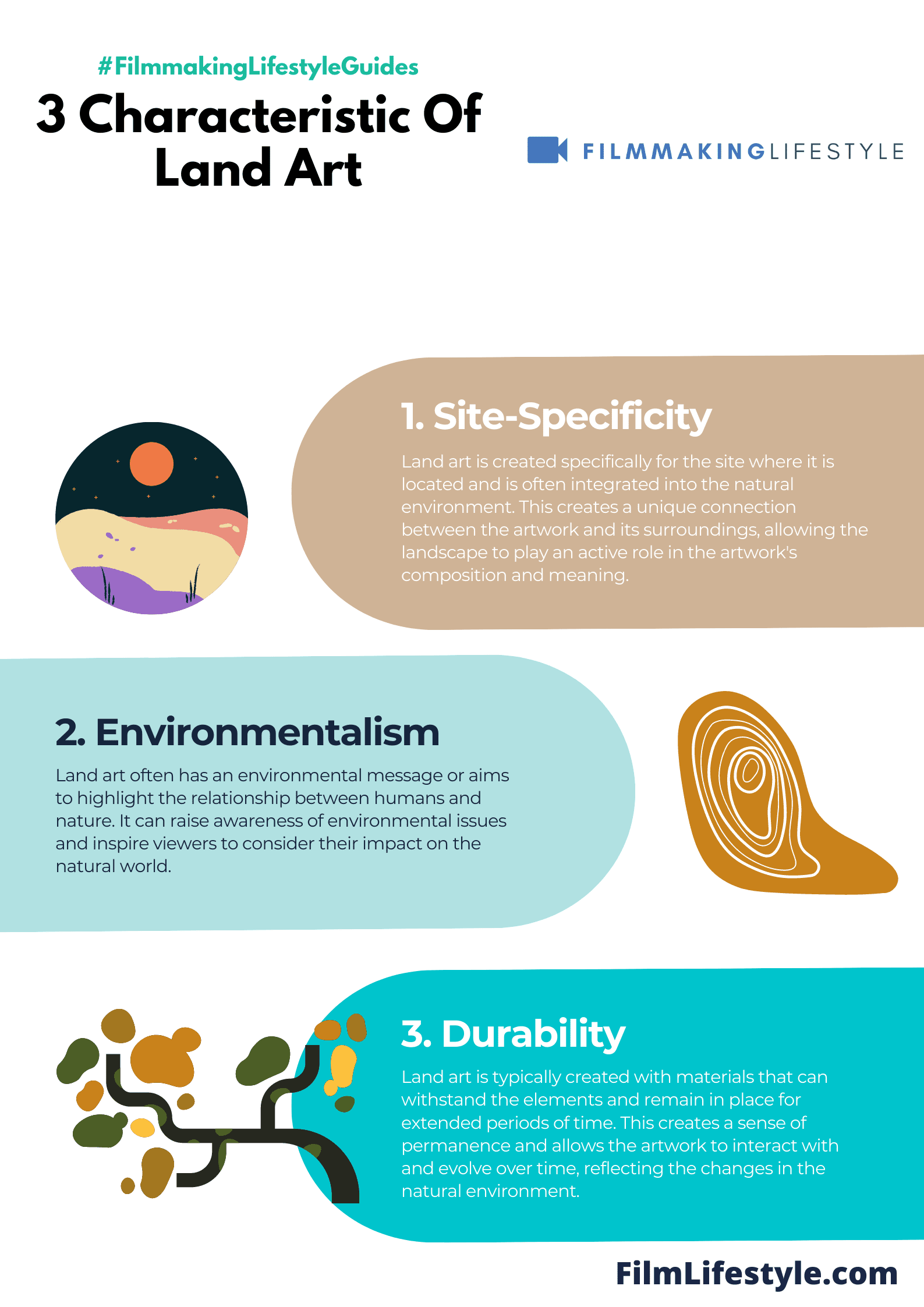

Land art is an art movement where the natural landscape and the work of art are inextricably linked.

Artists use the earth as their canvas, creating sculptures and patterns using natural materials like rocks, soil, and plants.

How Does Land Art Affect Viewers?

Land art demands physical interaction and contemplation of the environment from viewers.

It encourages a deeper appreciation for nature and often provokes thoughts about humanity’s impact on the Earth.

What Influence Has Land Art Had On Museums And Galleries?

Land art has prompted the inclusion of Earthworks documentation in museum and gallery collections.

Additionally, it has fostered collaborations with filmmakers and photographers to capture the impermanent artworks.

How Does Land Art Reflect On Human Legacy?

Land art reflects on the impermanence of human endeavors and our role on the planet.

It contrasts our temporary existence with the vastness of geological time scales.

Why Is Land Art Significant In Today’s Cultural And Environmental Discourse?

Land art is significant because it inspires artists and the public to think holistically about the intersection of art and the environment.

It emphasizes a mindful approach to our cultural and environmental legacy.