We have a special article today from Zander Weaver, which details his process for making a feature film. In the article, he covers how to make a movie and explains the reasoning behind each of his choices along the way. This is a must read.

Take it away Zander!

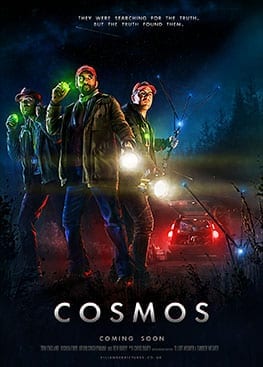

My name is Zander Weaver and alongside my brother, Elliot, I’ve just spent the last 5 years directing and producing my debut feature film – a sci-fi adventure called COSMOS.

We made the film with limited gear, three crew and no budget set aside. We undertook every key crew role during the production with the exception of writing the score and in this article I want to share with you a few things about how we did it.

This is going to be a no-nonsense breakdown of a few of the most important creative elements that went into Cosmos, why they matter and some tips we picked up along the way. Hopefully it’ll be an insight that will inspire you to grab the nearest camera and get cracking on your debut feature or short asap.

You’ve probably heard it a million times, but we really do live in an age where anyone can make films, there really are no excuses, the power is in your hands.

In reality, the list of key ingredients could be as long as my arm, but I’m going to focus on just a few. We’re going to talk storyboarding, lighting, camera blocking and editing.

We’ll address how to make life easier when making a no budget movie, how to keep creative ideas flowing, how to make your movie look like it cost more than it did and how to keep shots compelling. As well as a final bonus point, but you’ll have to read to the end for that (or just scroll down!)

To whet your appetite, here’s the film’s trailer:

How To Make A Movie – Why No Budget?

Before we get into all that, why did we decide to make our film with no-budget? And why should you consider doing the same?

The best answer for you will come from this 12-minute behind-the-scenes featurette we’ve recently released about the whole journey that went into making a no-budget feature…

We didn’t have to make Cosmos this way – we chose to do it this way – we chose to stop delaying or making excuses about what we needed and why we couldn’t make it yet because… yes you can fundraise, yes you can Kickstart if you want… we didn’t. Instead we chose to get out there and just make that happen.

So let’s get down to business.

1. Storyboarding: Make Your Life Easy

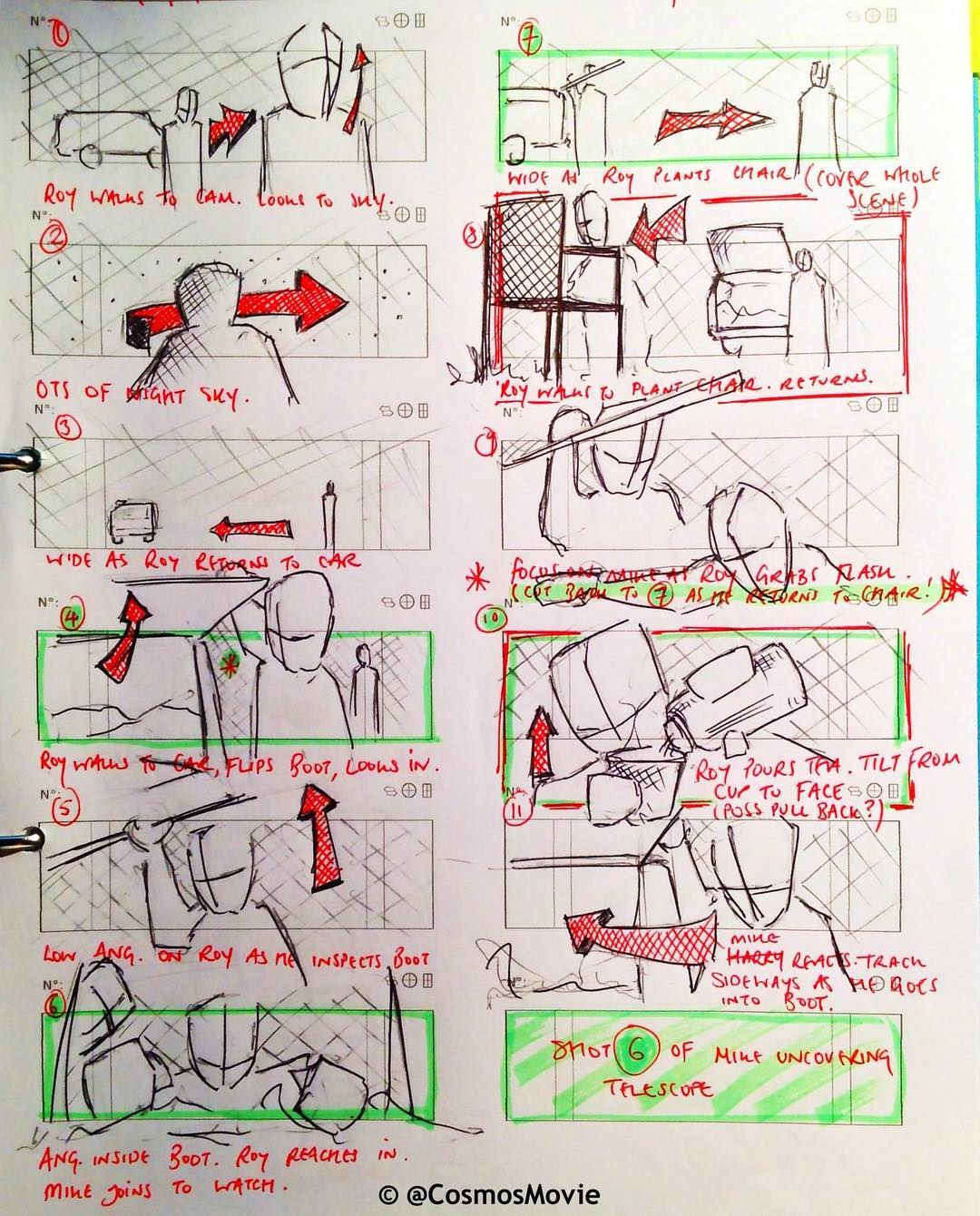

First up: storyboarding. You know the deal – quick, gestural sketches that help your team understand what you’re looking for.

The value of them is clear on a large scale production, but how about when your crew totals 3 (including you and your brother!), are they still useful then?

Absolutely. They’re not just important in communicating ideas to other people, they’re valuable because they help you cement your ideas about your film.

Unless you’ve got years of experience shooting drama, you’re not going to be able to stroll onto set and make up your coverage. Well, actually you can, but it’s not advisable – you’ll most likely walk away with mediocre, safe, uninspiring material.

Cinematography is not the be all and end all of storytelling on screen, but it is a language and choosing to play fast and loose with that vocabulary is like trying to express yourself in French when you’ve only had a couple of French lessons.

You might get by, you might find your way to the toilets or order that cheese baguette, but you’ll never be able to tell someone you love them or console a friend in a time of need. Film is about those deep rooted human emotions and fully engaging those, requires consideration.

Storyboarding is the time for that consideration. Elliot and I sketched out 1055 storyboard frames for the entire film. Every shot was planned.

We dedicated a month of evenings after work to completing the process. We put music on that fit the tone of the scene and bounced ideas off each other. How about this? How about that?

It was a safe environment for ideas and creativity and when it was all done we had our road map, our plan. If you have a plan you can always deviate, you can choose to grab a different shot or jump on an opportunity when it pops up because you’re confident in what you need.

Making Cosmos was like trying to direct a movie with your hair on fire, while riding a unicycle. Set up the lights, rig the camera and slider, mount the mic and set up the audio recorder, block the actors and rehearse.

- Are the lines correct?

- Are they wearing the correct costume?

- Are the right props in the right places?

- Do we have focus marks?

- Are we running out of time?!

One question we definitely did not need to be asking in those moments was: “what shot should we get here?”, that space is not safe, that space is not ripe and ready for creative ideas, it’s one of time constraints and pressures.

So be kind to yourself, create your roadmap, get inspired, grab a pencil and pop some music on. You don’t have to be Da Vinci, stickmen will do fine. If you’re working on a small film, the drawings are mainly for you anyway.

If you want to learn more about our storyboarding process and dig a bit deeper, check out this post: “Storyboarding – Make Your Movie Before You Make Your Movie”

2. Lighting: Add Production Value

Photography is the combination of two Greek words and literally means written in light… making a Photographer a light-writer. Legendary cinematographer John Alton is famed for his phrase and book Painting with Light and that is what we, as filmmakers, must strive to do.

Light can sculpt and describe a scene or character, it can hide or reveal key areas of your frame, it can enhance suspense and evoke emotion.

As filmmakers, we ignore its power at our own peril.

As with all indie films, our resources were limited, but that’s not always a bad thing as it forces you to get creative in finding solutions.

So yes, we had 3 LED panel lights and sometimes a more powerful 2kW “Blonde”… but we also used iPads, torches, desk lamps and even car high-beams as lighting sources.

Don’t be afraid if you haven’t got loads of gear, be creative. Light is light, it doesn’t matter whether it’s coming from an Arri, a Dedo or a desk lamp.

The industry leaders are there because they make the process easier and faster, but you should be as comfortable lighting an actor with an assortment of practical lights as you are working with professional lamps.

It wasn’t uncommon for us to use the headlights on our car to fill out a scene and we lit an entire night forest with 3 LED Panel lights and some battery torches.

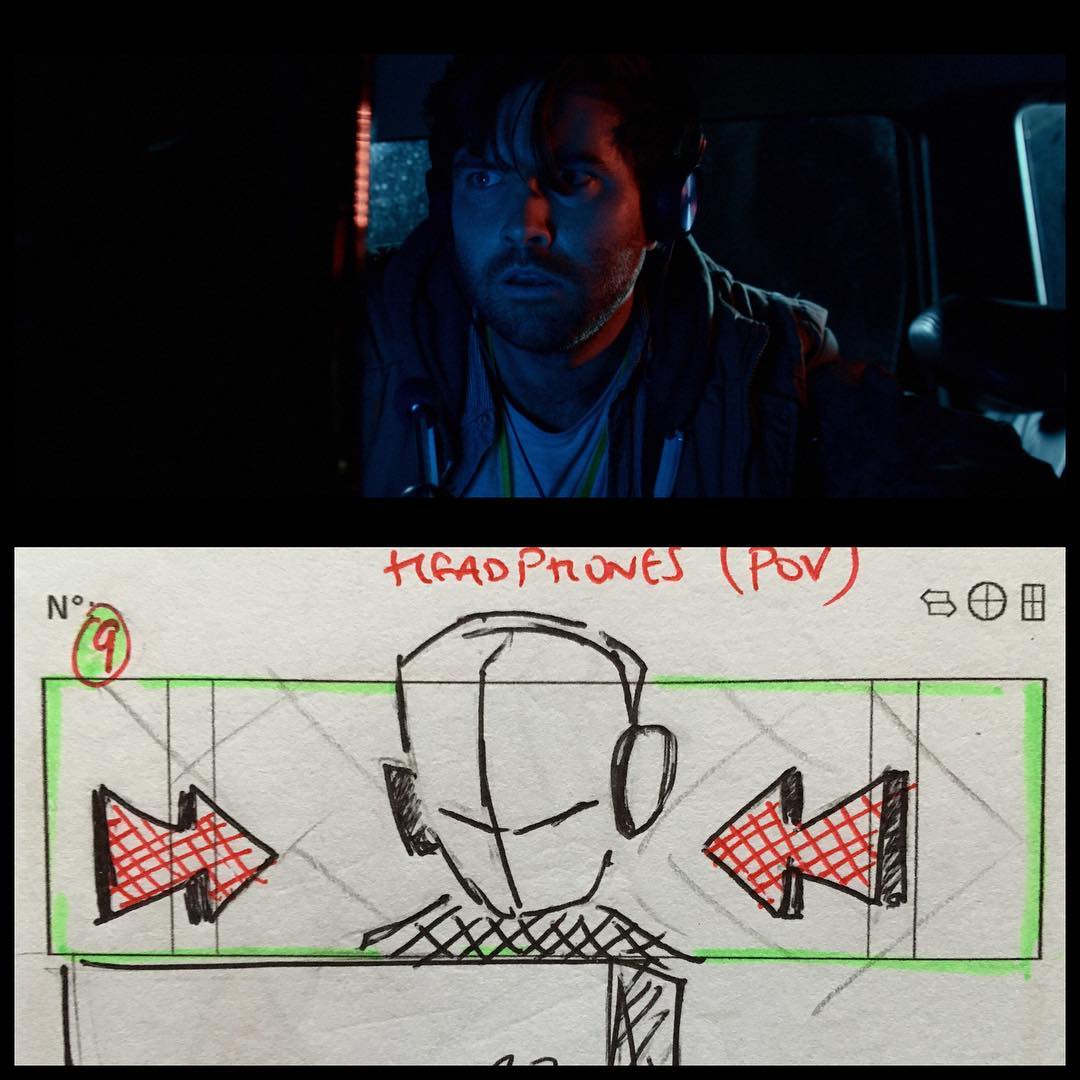

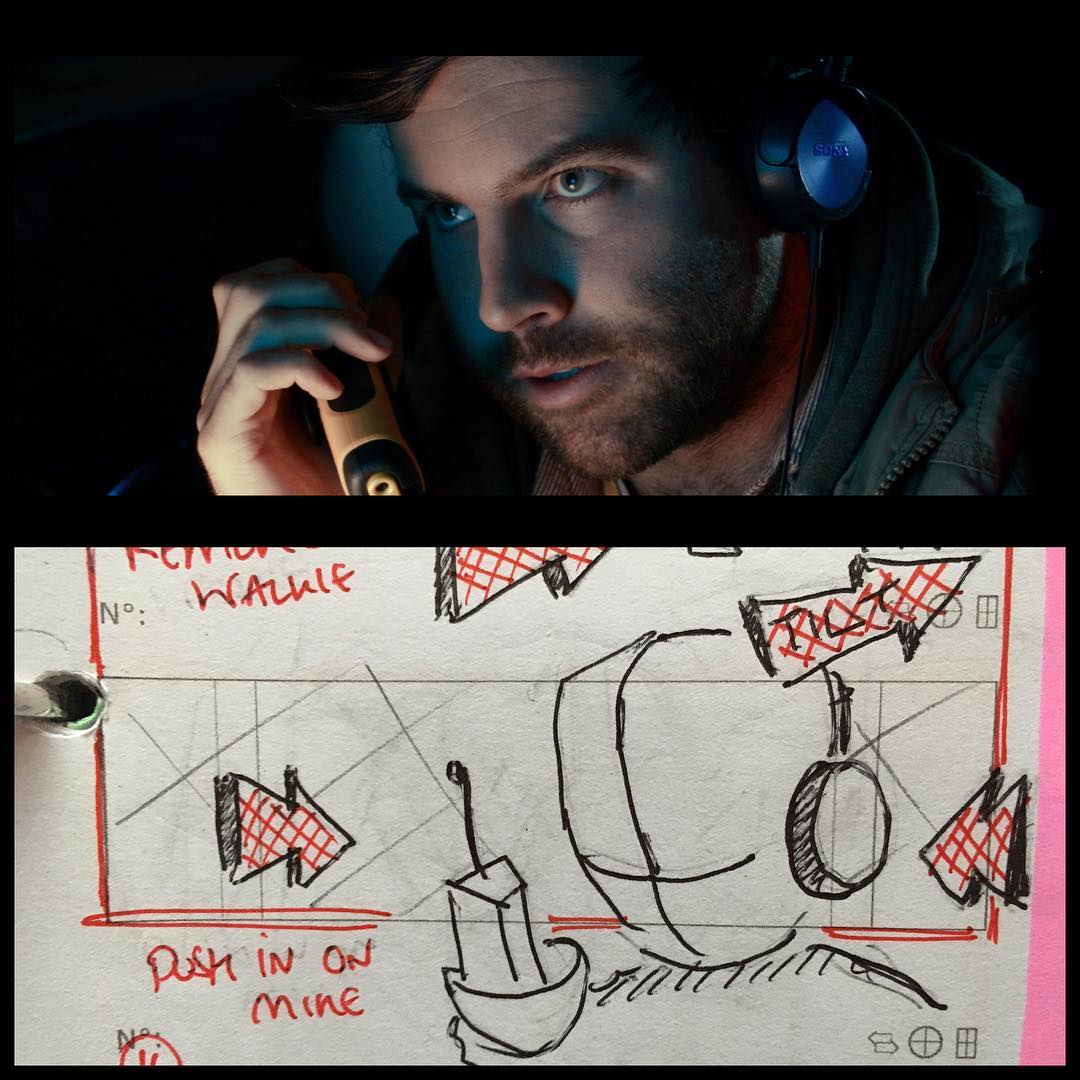

We’re obsessed with Low Key Lighting. This style creates high contrast, visually striking and dramatic imagery. The light itself is used in a very selective way, so that only specific portions of the image are illuminated, while other areas are allowed to roll off into deep shadow.

To create a low-key lighting effect, simply adapt the traditional three-point lighting model of key light, fill light and back light. Low-key lighting basically restricts the fill light or removes it altogether, accentuating the shape and contours of the subject and adding a stunning sense of depth and drama.

We used this simple technique on Cosmos in every single frame of the film. Yes, the style lends itself to the subject matter but also it helps create a “budgeted” look.

My advice to you would be try lighting your actors with just two lights instead of three . Experiment with the strength of the light and move the lamps around until you create interesting shapes and shadows on their faces.

Many people think there’s a secret trick to lighting when actually it’s frighteningly simple: just open your eyes and watch how the light falls… tweak it until you like it.

Don’t worry about being “good” – some people will like what you do, some people won’t. That’s art: it’s supposed to be divisive. Do your thing, be yourself, that’s what matters.

Also, use colored light! Don’t light everything with a single color or white. Mix things up. Have a blue backlight and a green key light, or a red underlight, or whatever!

Don’t wait to force a color palette into your image during the grade. It’ll never work as well as committing to a lighting look while shooting – this will also help you learn!

The best cinematographers still working in the business learnt their craft on film. They’re the best because they learnt in an age without “undo”, they have the ability and the confidence to commit to a look on set and not fall back on post.

Sure, think creatively about the relationship between photography and its manipulation later, but be bold and be brave, make your decisions about your look before you get to the grade. Your image, your film and your audience will thank you for it.

If you shoot something and hate how it turns out in the edit… you’ve learnt something! You’ve learned what not to do next time, which is the exact same as learning what to do.

You can’t learn if you don’t make mistakes. Forget what they teach you at school… mistakes are GOOD!

Again we have a full process on our exterior night lighting setups here.

3. Blocking: Keep Your Shots Compelling

The one single aspect of filmmaking I believe gets consistently overlooked, is blocking. Time and again we hear filmmakers talking about gear, lighting, cameras and resolution. We hear about soundtracks and foley or casting, acting and writing, but we rarely hear people discuss blocking.

Why that is, I don’t honestly know, because a shot without blocking is only half a shot.

Blocking is the intricate dance between audience and subject, the camera moves in closer and we as an audience lean in, or a character steps up to camera and becomes more dominant in frame.

We can play with audience focus and attention, we can shift their eyes from one corner of the frame to another. We can follow a character across screen and find ourselves framed in a new angle and we didn’t need to cut in between.

Boring coverage and boring movement make boring movies. I believe this is at the very heart of the art of filmmaking and so few filmmakers learning their craft recognise its significance.

Check out this perfect summary of blocking by Dan Fox on YouTube:

A large proportion of Cosmos is set inside a car, so initially it seems there isn’t a huge amount of potential for creative blocking in such a confined space. But, actually, good blocking is the very thing that, we believe, ensures our film doesn’t get stale and repetitive despite being told in one main location.

There’s a lot you can do when you block that holds the audience’s attention and being in such a small space meant we needed to be creative.

We’re certainly not masters of the craft, we’re all continually learning with each new project, but I truly implore you to take blocking seriously.

Pay attention to this one factor, hone your understanding of it and you’ll immediately jump out above the crowd of other filmmakers out there. You’ll go from someone with a camera and an idea to a storyteller with a vision and understanding of cinematic language.

4. Editing: Give Yourself A Break

Editing is where your film will go from an assortment of insignificant shots to your masterpiece. The relationship between cuts and where you choose to place your audience’s focus is one of the single, most critical elements in the effectiveness of a film.

In the hands of less experienced editors, classic movies would have crumbled into disjointed, voiceless messes of imagery. So don’t be afraid to take your time. Elliot and I spent 10 months picture cutting Cosmos, buried deep in our work behind closed doors.

It was creatively, mentally and emotionally demanding. To break up the monotony, we would often grab a coat, put on some walking shoes and go for a stroll in a local woods.

Never underestimate the power of taking a break. That little voice in the back of your head may burn you for it, but that same voice will eventually shut up and start thinking about solutions to the problems you’re facing.

You’ll disengage that spinning wheel momentarily and just when you’ve let the problem drift away that voice will suddenly erupt: “HOW ABOUT THIS…”

In an interview, Steven Spielberg once expressed his discomfort with the speed of digital editing. Sure it was fast, instant and exciting, but when cutting on film he could lay out ideas and then leave his editor to it while he took a stroll around the studio.

On those strolls he might see something, meet someone or just have an idea pop into his head that would inform the edit of his film.

So be like Spielberg and take breaks. The answers will come if you give them the space.

We cut on Final Cut Pro 7 (and even did our full sound mix in the same program). Yes, we designed and mixed an entire feature film in a piece of software that is not designed for that purpose.

One filmmaker recently commented on a forum “You cut on FCP7?! Are we living in 2009?!” we didn’t continue the conversation for fear of starting an unnecessary argument (thank you internet), but this individual is missing the point.

Many Oscar nominated and winning films were cut on FCP7. It revolutionised the industry and was used day-to-day by the best cutters in the business – fact that hasn’t changed simply because a new version is available.

Editing is a craft, can the software allow me to cut my footage into a film? Yes? Well then it’s exactly what I need.

- I don’t need 3D capability,

- I don’t need 8K resolution,

- I don’t need a super cool transition or the ability to stablize my footage (actually FCP7 can do that).

If it’s good enough for Walter Murch and recognised by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, it’s definitely good enough for me.

The moral of this particular story is, don’t be like that guy, don’t think that gear and software will make you a better filmmaker.

There are now open source visual effects programs that blow the pants off the software ILM used to create Jurassic Park back in the early 90s, but do we see everyone creating Oscar worthy VFX from their bedroom? No. Because it’s not about the gear, it’s about what you can do with it.

This is a such an obvious statement to make but you’d be amazed by the number of times we get asked about our gear, in particular “what lenses did you use”.

Of course, equipment is important, it’s an enabler and in regards to lenses it can directly affect the aesthetic of your film. But let’s keep it in perspective and not go gear crazy. Spielberg with an iPhone could make a better movie than I could with a Panavision film camera.

Without people, the equipment is a useless assortment of screws, wires and glass.

If you are a budding filmmaker out there, or even an experienced filmmaker, who’s holding back because they’re worried that they don’t have enough equipment, please shake it off.

Grab a camera, any camera will do, literally, if a story can be told with stick figures and a flipbook it can certainly be told with whatever camera you have to hand.

Engage in the challenge, push your understanding, demand more of your gear than others may and you’ll be stronger and wiser because of it.

5. The Team: Inspire Others And They’ll Inspire You

My final piece of advice would be find the right PEOPLE.

Having the right people around you is what will keep you going when things get hard. It’s what will push your standards beyond your expectations and what, ultimately will make the entire experience worthwhile.

The friends, collaborators and professional relationships you’ll develop when taking on a big project will be some of the most valuable you’ll ever develop.

I can honestly say that this was the single most important element of the process for us.

- We found actors who were dedicated and passionate, hard working and generous with their time,

- we had friends come by and offer a helping hand or allow us to film on their property,

- we had people offer equipment to the cause for free and even had delicious home baked food brought to us on special occasions that kept us working through the night.

There’s no tutorial or trick for this, it takes time and persistence and patience and it requires you to keep looking.

If I’d have known at the beginning of Cosmos, the scale of what we’d ask of our actors and the unique character traits they’d need for us all to progress through this production smoothly, I’d have thought we’d never find them. I may have even given up hope, and yet here we are, our first movie produced with some of the greatest collaborators I could ever have hoped to find. So keep looking, they’re out there.

Good luck with your filmmaking endeavours and thanks for reading.

If you’d like to know more about COSMOS, please consider following our Facebook, Instagram and Twitter pages for regular BTS content. I’ll hopefully see you over there!

We hope this article on how to make a movie has been inspiring. Special thanks to Zander for writing such a thought provoking and ‘no stone left unturned’ account of his process.

Have you made a film? Let us know in the comments below.

Matt Crawford

Related posts

4 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Fantastic advice!

Thanks, Joyce.

Awesome article.

Thanks a lot! Appreciate the feedback.