- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

Italian neorealism reshaped cinema with its raw portrayal of post-war society.

It’s a movement that emerged as a beacon of authenticity, challenging the escapism of glossy studio productions.

We’ll jump into the gritty streets and the poignant narratives that define this influential film style.

You’re about to discover how neorealism became the mirror reflecting Italy’s soul to the world.

ITALIAN NEOREALISM

What Is Italian Neorealism?

Italian Neorealism is a genre of Italian film that emerged in the 1940s.

This type of filmmaking style captures stories from working-class life in Italy. The movement has its roots in post-war Italy, where many citizens were living in poverty after the war had ended.

The films were characterized by their use of non-professional actors, location shooting, improvised dialogue, and lack of moral censorship.

Origins Of Italian Neorealism

The seeds of Italian neorealism were sown in the fertile ground of political and economic turmoil.

Post-World War II Italy was marked by rubble, both physically and metaphorically, as the nation grappled with the aftermath of Fascism and war.

This era fostered a new breed of filmmakers who turned their cameras away from the idealized fiction of the past and toward the stark realities of Italian life.

Key precursors to neorealism can be traced to the literary movement known as verismo – a pursuit of realism in literature – and to earlier films that showed a predisposition to social commentary.

It is within this context that neorealism began to take shape, offering not just entertainment but a mirror reflecting Italy’s societal challenges.

- Visionary directors such as Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica didn’t just depict life – they immersed audiences in it,

- Films like Rome, Open City and Bicycle Thieves epitomized the movement’s ethos, portraying the struggles of everyday people with unprecedented authenticity.

By filming on location, Italian neorealism brought a palpable sense of place and realism unprecedented in the cinema landscape.

The streets themselves became a sort of character within the narrative – full of life, struggle, and resilience.

This innovative approach to storytelling was complemented by the use of non-professional actors, lending an air of authenticity that professional actors could rarely match.

Our understanding of Italian neorealism also relies on its thematic content, which often focused on the poor and working class.

The neorealist directors were particularly concerned with social issues – emphasizing themes of justice, dignity, and the battle for survival amidst economic hardship.

- The movement’s attention to the plight of the disenfranchised was reflective of its humanistic core,

- By highlighting these struggles through cinema, the movement provided not just a critique but a form of solidarity with the oppressed.

Through these techniques and themes, Italian neorealism laid the groundwork for future filmmakers around the world, influencing everything from French New Wave to modern independent cinema.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Italian Neorealism film movement, check out our in-depth profile and explore our comprehensive timeline of film movements to see where it fits in cinema history.

It’s clear the movement’s impact far surpassed Italy’s borders, reshaping the global cinematic dialogue with its innovative, empathetic approach to filmmaking.

Key Characteristics Of Italian Neorealism

Italian neorealism emerged as a distinctive force in the aftermath of World War II.

We attribute its unique style and perspective to several key characteristics, ones that set it apart from Hollywood cinema and previous Italian productions.

These traits not only defined the movement but also influenced future generations of filmmakers who sought to capture authenticity in their work.

Location Shooting and Natural Lighting played a crucial role in the visual aesthetic of neorealist films.

Directors like Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica favored shooting in the streets, amidst the ruins, and in the everyday spaces where the ordinary Italian lived and struggled.

The result was a stark contrast to the polished sets of conventional studios.

Our favorites like Rome, Open City and Bicycle Thieves showcased this raw and unfiltered look into the lives of their characters.

Employing Non-Professional Actors was another hallmark of Italian neorealism.

This choice wasn’t merely about budget constraints; it was a conscious decision to bring an authentic edge to storytelling.

Non-actors brought their own experiences and emotions, often mirroring the realities of their characters.

This helped stories resonate on a much deeper level than the oftentimes melodramatic performances found in traditional cinema.

We see Italian neorealism’s narratives as defined by a sense of Social Consciousness.

Films from this era didn’t shy away from addressing the societal issues of the time:

- Poverty,

- Oppression,

- Injustice,

- The aftermath of war.

They highlighted the human condition in a way that was both compassionate and unflinching, emphasizing struggle and resilience among the working class.

Themes of Hope and Moral Questions were invariably present.

Even though the often bleak circumstances depicted, neorealist films usually left room for hope.

They prompted viewers to contemplate moral dilemmas, placing them in the shoes of characters facing impossible choices.

These stories compelled audiences to consider the societal structures at play and, perhaps, to envision a path toward a fairer world.

Understanding Italian neorealism’s intrinsic qualities gives us insight into the profound impact it had on cinema.

Its dedication to realism, depicted through unconventional filmmaking techniques, continues to inspire filmmakers who aim to tell genuine stories that reflect societal challenges and human emotions.

Here’s our detailed video covering the history, origins and famous films & filmmakers of the Italian neorealist period:

The Key Films Of Italian Neorealism

Let’s take a look at some of the central films of the Italian Neorealism movement.

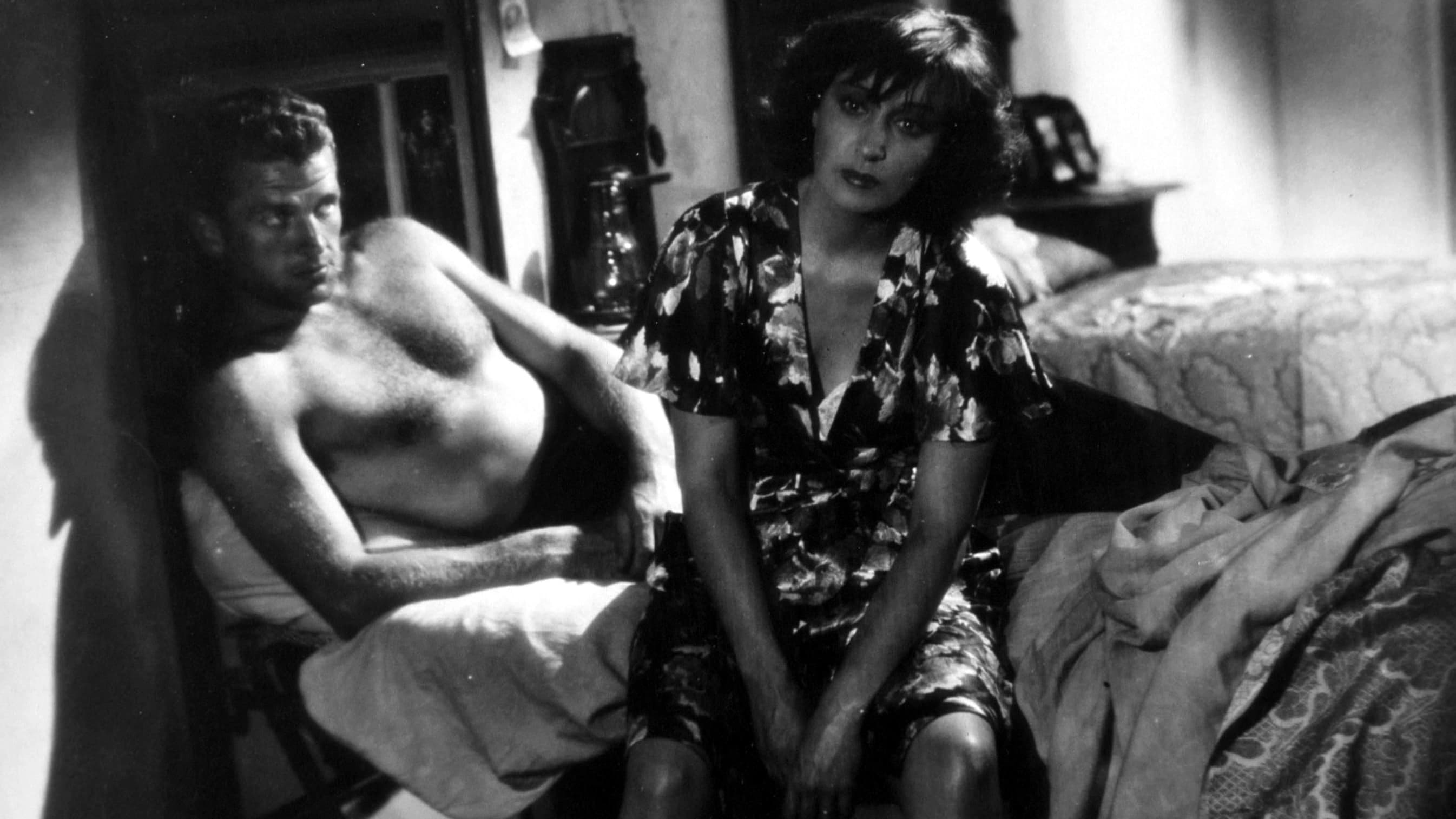

Ossessione (1942)

No poster available

Obsession

1944 • 2h 20min • ★ 7.529/10 • Italy

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Clara Calamai, Massimo Girotti, Dhia Cristiani, Elio Marcuzzo, Vittorio Duse

Gino, a drifter, begins an affair with inn-owner Giovanna as they plan to get rid of her older husband.

Ossessione is based on the 1934 novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, by James M. Cain.

Luchino Visconti’s first feature film is considered by many to be the first Italian neorealist film, though there is some debate about whether such a categorization is accurate.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=FOZ6Z9JEJaM

Set in the flatlands of the Po delta, traces the love affair between an itinerant laborer and the restless wife of a trattoria owner, which leads to the murder of the boorish husband.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Clara Calamai, Massimo Girotti, Juan de Landa (Actors)

- Luchino Visconti (Director) - Luchino Visconti (Writer) - Libero Solaroli (Producer)

- English, Spanish, French (Playback Language)

- English, Spanish, French (Subtitles)

Rome, Open City (1945)

Rome, Open City

Our battle has barely begun.

1945 • 1h 43min • ★ 8.02/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Aldo Fabrizi, Marcello Pagliero, Harry Feist, Anna Magnani, Maria Michi

In WWII-era Rome, underground resistance leader Manfredi attempts to evade the Gestapo by enlisting the help of Pina, the fiancée of a fellow member of the resistance, and Don Pietro, the priest due to oversee her marriage. But it’s not long before the Nazis and the local police find him.

Rome, Open City

Our battle has barely begun.

1945 • 1h 43min • ★ 8.02/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Aldo Fabrizi, Marcello Pagliero, Harry Feist, Anna Magnani, Maria Michi

In WWII-era Rome, underground resistance leader Manfredi attempts to evade the Gestapo by enlisting the help of Pina, the fiancée of a fellow member of the resistance, and Don Pietro, the priest due to oversee her marriage. But it’s not long before the Nazis and the local police find him.

Roberto Rossellini’s film was one of the first films of this genre which focused on telling stories about how difficult life could be without being censored but also show how much people had to struggle under fascism and war.

Italians wanted their voices to be heard through cinema so they often used non-professional actors, improvised dialogue, location shooting with little or no set design

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Anna Magnani, Marcello Pagliero, Aldo Fabrizi (Actors)

- Roberto Rossellini (Director) - Sang-gi Lee (Writer) - Joon-hwan Choi (Producer)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

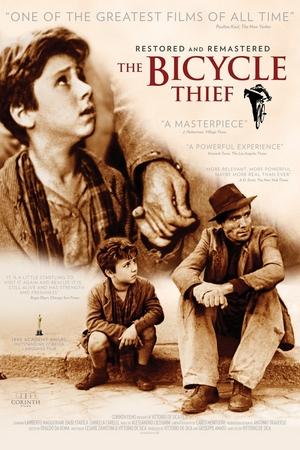

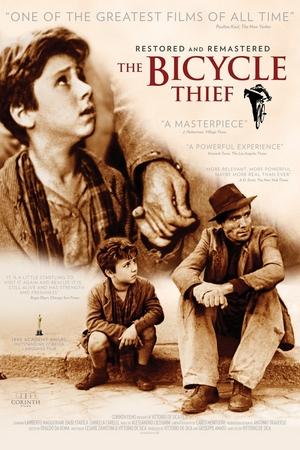

The Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Bicycle Thieves

The Prize Picture They Want to Censor!

1948 • 1h 29min • ★ 8.175/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Lamberto Maggiorani, Enzo Staiola, Lianella Carell, Gino Saltamerenda, Vittorio Antonucci

Unemployed Antonio is elated when he finally finds work hanging posters around war-torn Rome. However on his first day, his bicycle—essential to his work—gets stolen. His job is doomed unless he can find the thief. With the help of his son, Antonio combs the city, becoming desperate for justice.

Bicycle Thieves

The Prize Picture They Want to Censor!

1948 • 1h 29min • ★ 8.175/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Lamberto Maggiorani, Enzo Staiola, Lianella Carell, Gino Saltamerenda, Vittorio Antonucci

Unemployed Antonio is elated when he finally finds work hanging posters around war-torn Rome. However on his first day, his bicycle—essential to his work—gets stolen. His job is doomed unless he can find the thief. With the help of his son, Antonio combs the city, becoming desperate for justice.

Hailed around the world as one of the greatest movies ever made, the Academy Award-winning Bicycle Thieves, directed by Vittorio De Sica (Umberto D.), defined an era in cinema.

In poverty-stricken postwar Rome, a man is on his first day of a new job that offers hope of salvation for his desperate family when his bicycle, which he needs for work, is stolen.

With his young son in tow, he sets off to track down the thief.

Simple in construction and profoundly rich in human insight, Bicycle Thieves embodies the greatest strengths of the Italian neorealist movement: emotional clarity, social rectitude, and brutal honesty.

Heralded as the greatest film ever made on release, winning an Oscar in 1949 and topping the Sight & Sound film poll in 1952.

De Sica’s seminal work of Italian neorealism has had an impact on cinema worldwide from release to the present day, with filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray and Ken Loach claiming the film as a direct influence on their own.

Bicycle Thieves tells the story of Antonio, a long unemployed man who finally finds employment putting up cinema posters for which he needs a bicycle.

His wife pawns all the family linen to redeem the already pawned bicycle and for Antonio salvation has come, until the bicycle is stolen.

Antonio and his son take to the streets in a desperate search to find the bicycle.

Bicycle Thieves is as much about the position of Italians in post-War, post-Fascist Italy as the relationship between father and son, told through the labyrinth of the cinematic city with De Sica’s arresting visual poetry.

Defining neorealism, a small period of filmmaking that focused on simple, humanist stories, Bicycle Thieves was one of the most captivating and moving. Now presented in a new 4K restoration from the original camera negative.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Lamberto Maggiorani, Enzo Staiola, Lianella Carell (Actors)

- Vittorio De Sica (Director) - Vittorio De Sica (Writer) - Giuseppe Amato (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

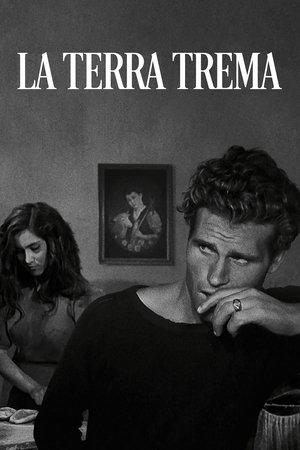

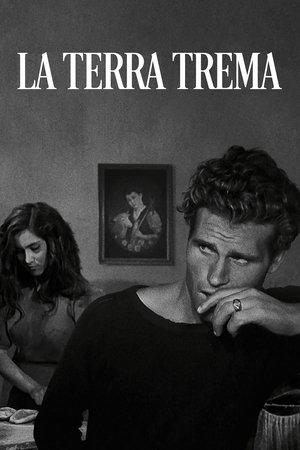

La terra trema (1948)

La Terra Trema

1949 • 2h 40min • ★ 7.723/10 • Italy

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Antonio Arcidiacono, Giuseppe Arcidiacono, Venera Bonaccorso, Nicola Castorino, Rosa Catalano

In rural Sicily, the fishermen live at the mercy of the greedy wholesalers. One family risks everything to buy their own boat and operate independently.

La Terra Trema

1949 • 2h 40min • ★ 7.723/10 • Italy

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Antonio Arcidiacono, Giuseppe Arcidiacono, Venera Bonaccorso, Nicola Castorino, Rosa Catalano

In rural Sicily, the fishermen live at the mercy of the greedy wholesalers. One family risks everything to buy their own boat and operate independently.

The movie is loosely adapted from Giovanni Verga’s novel The House by the Medlar Tree.

The picture features non-credited non-professional actors, Antonio Arcidiacono, Giuseppe Arcidiacono, and many others. It is a docufiction in the Sicilian language.

The story takes place in Aci Trezza (Jaci Trizza), a small fishing village on the east coast of Sicily, Italy.

It tells about the exploitation of working-class fishermen, specifically that of the eldest son of a very traditional village family, the Valastros.

Antonio convinces his family to mortgage their house in order to catch and sell fish themselves and make more money than they were already receiving from the wholesalers who had controlled the market with their low prices for a long time.

Everything goes well until a storm ruins the family’s boat, leaving them with nothing to keep the new business going.

Following this disaster, the family experiences several awful events such as having to leave the house, the death of the grandfather, and ‘Ntoni and his brothers being obliged to return to fish for the wholesalers.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Antonio Arcidiacono, Giuseppe Arcidiacono (Actors)

- Luchino Visconti (Director) - Antonio Pietrangeli (Writer) - Salvo D'Angelo (Producer)

- English, French, Italian (Playback Language)

- English, French, Italian (Subtitles)

Germany, Year Zero (1948)

Germany, Year Zero

A soldier can lose everything but his courage.

1948 • 1h 12min • ★ 7.7/10 • France

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Edmund Moeschke, Ernst Pittschau, Ingetraud Hinze, Franz-Otto Krüger, Erich Gühne

In the ruins of post-WWII Berlin, a twelve-year-old boy is left to his own devices in order to help provide for his family.

Germany, Year Zero

A soldier can lose everything but his courage.

1948 • 1h 12min • ★ 7.7/10 • France

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Edmund Moeschke, Ernst Pittschau, Ingetraud Hinze, Franz-Otto Krüger, Erich Gühne

In the ruins of post-WWII Berlin, a twelve-year-old boy is left to his own devices in order to help provide for his family.

The concluding part of Roberto Rossellini’s celebrated War Trilogy, Germany Year Zero, is presented here in a new restoration.

Amidst the war-torn ruins of Berlin in the period immediately after the Second World War a twelve-year-old boy, Edmund, struggles to support his family his ailing father and un-registered brother unable to provide for them.

Left to his own devices, Edmund wanders around the devastated city, getting caught up in black market schemes and falling prey to the pernicious influence of a Nazi-sympathising former teacher with tragic consequences.

This heart-rending portrait of a decimated post-war European city is a damning indictment of war and fascism and remains one of the most affecting films in the history of cinema.

Francesco, giullare di Dio (1950)

The Flowers of St. Francis

A Movie for Today... And All Time

1950 • 1h 27min • ★ 7.129/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Aldo Fabrizi, Gianfranco Bellini, Peparuolo, Severino Pisacane, Roberto Sorrentino

In a series of simple and joyous vignettes, director Roberto Rossellini and co-writer Federico Fellini lovingly convey the universal teachings of the People’s Saint: humility, compassion, faith, and sacrifice. Gorgeously photographed to evoke the medieval paintings of Saint Francis’s time, and cast with monks from the Nocera Inferiore Monastery, The Flowers of St. Francis is a timeless and moving portrait of the search for spiritual enlightenment.

The Flowers of St. Francis

A Movie for Today... And All Time

1950 • 1h 27min • ★ 7.129/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Aldo Fabrizi, Gianfranco Bellini, Peparuolo, Severino Pisacane, Roberto Sorrentino

In a series of simple and joyous vignettes, director Roberto Rossellini and co-writer Federico Fellini lovingly convey the universal teachings of the People’s Saint: humility, compassion, faith, and sacrifice. Gorgeously photographed to evoke the medieval paintings of Saint Francis’s time, and cast with monks from the Nocera Inferiore Monastery, The Flowers of St. Francis is a timeless and moving portrait of the search for spiritual enlightenment.

The Flowers of St. Francis is a 1950 film directed by Roberto Rossellini and co-written by Federico Fellini.

The film is based on two books, the 14th-century novel Fioretti Di San Francesco Little Flowers of St. Francis and La Vita di Frate Ginepro (The Life of Brother Juniper)

Both of the books relate the life and work of St. Francis and the early Franciscans. I Fioretti is composed of 78 small chapters.

The novel as a whole is less biographical and is instead more focused on relating tales of the life of St. Francis and his followers.

The movie follows the same premise, though rather than relating all 78 chapters, it focuses instead on nine of them.

Each chapter is composed in the style of a parable, and, like parables, contains a moral theme.

- Factory sealed DVD

- Isabella Rossellini, Gianfranco Bellini, Aldo Fabrizi (Actors)

- Roberto Rossellini (Director) - Brunello Rondi (Writer)

- English (Subtitle)

- English (Publication Language)

I Vitelloni (1952)

No poster available

I Vitelloni

We are the hollow men in this last of meeting places we grope together and avoid speech. Gathered on this beach of the torrid river.

1953 • 1h 43min • ★ 7.646/10 • France

Directed by: Federico Fellini

Cast: Franco Interlenghi, Alberto Sordi, Franco Fabrizi, Leopoldo Trieste, Riccardo Fellini

Five young men dream of success as they drift lazily through life in a small Italian village. Fausto, the group's leader, is a womanizer; Riccardo craves fame; Alberto is a hopeless dreamer; Moraldo fantasizes about life in the city; and Leopoldo is an aspiring playwright. As Fausto chases a string of women, to the horror of his pregnant wife, the other four blunder their way from one uneventful experience to the next.

Italian maestro Federico Fellini’s first international success is a nakedly autobiographical film that bears many of the formal and thematic concerns that recur throughout his work.

Set in the director’s hometown of Rimini, I Vitelloni follows the lives of five young vitelloni, or layabouts, who while away their listless days in their small seaside village.

Fausto (Franco Fabrizi), the leader of the pack, marries his sweetheart but finds himself constantly distracted by other women.

Meanwhile, would-be playwright Leopoldo (Leopoldo Trieste) continues work on his dreary plays, dreaming of staging them one day. Clownish Alberto (Alberto Sordi) still lives at home with his mother and sister, Olga (Claude Farell), while boasting of preserving the family honor by watching over her.

While the movie seems to pay little attention to Riccardo (Riccardo Fellini) and Moraldo (Franco Interlenghi), the latter eventually emerges as its key character, plainly serving as Fellini’s alter ego.

Federico Fellini’s breakthrough film, 1953’s I Vitelloni, is one of the cinema’s seminal stories about slacker males, and a highly entertaining one at that.

Following the unfortunate failure of his comedy The White Sheik, Fellini prepared to shoot La Strada (he would release that early masterpiece in 1954) but decided at the last minute to make an autobiographical feature about mischievous, drifting, 30-ish losers in a small, seaside town.

I Vitelloni clicked with international audiences and remains an obvious influence on such later classics as Breaking Away and Diner.

But there’s nothing like Fellini’s almost self-mocking fusion of gritty neo-realism with the audacious, illusionary style he would later be entirely linked.

The ensemble comedy follows the ever-diminishing fortunes of five young men who can’t define, let alone jump-start, their dreams, particularly the caddish Fausto (Franco Fabrizi), who thinks nothing of molesting the wife of his father-in-law’s best friend.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Franco Interlenghi, Alberto Sordi, Franco Fabrizi (Actors)

- Federico Fellini (Director) - Federico Fellini (Writer) - Jacques Bar (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

Umberto D. (1952)

Umberto D.

1952 • 1h 31min • ★ 7.89/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Carlo Battisti, Napoleone the Dog, Maria Pia Casilio, Lina Gennari, Elena Rea

When elderly pensioner Umberto Domenico Ferrari returns to his boarding house from a protest calling for a hike in old-age pensions, his landlady demands her 15,000-lire rent by the end of the month or he and his small dog will be turned out onto the street. Unable to get the money in time, Umberto fakes illness to get sent to a hospital, giving his beloved dog to the landlady's pregnant and abandoned maid for temporary safekeeping.

Umberto D.

1952 • 1h 31min • ★ 7.89/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Carlo Battisti, Napoleone the Dog, Maria Pia Casilio, Lina Gennari, Elena Rea

When elderly pensioner Umberto Domenico Ferrari returns to his boarding house from a protest calling for a hike in old-age pensions, his landlady demands her 15,000-lire rent by the end of the month or he and his small dog will be turned out onto the street. Unable to get the money in time, Umberto fakes illness to get sent to a hospital, giving his beloved dog to the landlady's pregnant and abandoned maid for temporary safekeeping.

Hailed by Martin Scorsese as “De Sica’s greatest achievement”, Umberto D surpasses even Bicycle Thieves in many critics’ opinions – rating as one of the greatest films of all time.

A heartfelt portrait of an impoverished retired civil servant who lives in a rented room in post-war Rome with only his beloved dog and a teenage housemaid as companions.

Faced with eviction when he can’t keep up with his rent, the old man struggles to make ends meet and maintain his dignity, but his growing despair leads him to contemplate suicide.

Written by De Sica’s long-standing collaborator Cesare Zavattini, Umberto D’s depiction of poverty, old age and loneliness – far from being a recipe for bleakness - is bursting with life.

Despite international acclaim with Cannes and Oscar nominations, it was castigated by the Italian government for airing the country’s ‘dirty laundry’ in public.

Today, though, Umberto D is universally considered not only as the apex of Italian Neorealism but as one of cinema’s masterpieces with a profound influence on generations of filmmakers.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Carlo Battisti, Maria Pia Casilio, Lina Gennari (Actors)

- Vittorio De Sica (Director) - Vittorio De Sica (Writer) - Giuseppe Amato (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

La Strada (1954)

La Strada

Filmed in Italy - where it happened!

1954 • 1h 55min • ★ 7.909/10 • Italy

Directed by: Federico Fellini

Cast: Giulietta Masina, Anthony Quinn, Richard Basehart, Aldo Silvani, Marcella Rovere

When Gelsomina, a naïve young woman, is purchased from her impoverished mother by brutish circus strongman Zampanò to be his wife and partner, she loyally endures her husband's coldness and abuse as they travel the Italian countryside performing together. Soon Zampanò must deal with his jealousy and conflicted feelings about Gelsomina when she finds a kindred spirit in Il Matto, the carefree circus fool, and contemplates leaving Zampanò.

La Strada

Filmed in Italy - where it happened!

1954 • 1h 55min • ★ 7.909/10 • Italy

Directed by: Federico Fellini

Cast: Giulietta Masina, Anthony Quinn, Richard Basehart, Aldo Silvani, Marcella Rovere

When Gelsomina, a naïve young woman, is purchased from her impoverished mother by brutish circus strongman Zampanò to be his wife and partner, she loyally endures her husband's coldness and abuse as they travel the Italian countryside performing together. Soon Zampanò must deal with his jealousy and conflicted feelings about Gelsomina when she finds a kindred spirit in Il Matto, the carefree circus fool, and contemplates leaving Zampanò.

Regarded by some as Federico Fellini’s finest work, and the winner of the first Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, La Strada is a masterpiece of 20th Century filmmaking.

Sold by her impoverished mother to Zampano (Anthony Quinn), a brutish fairground wrestler, waif-like Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina) lives a life of drudgery as his assistant.

After taking to the road with a traveling circus, a budding relationship with Il Matto/The Fool (Richard Basehart), a gentle-natured, tightrope walking clown, offers a potential refuge from her master’s clutches.

Trapped by her own servile nature, Gelsomina waivers, and Zampano’s volcanic temper erupts with tragic consequences.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Giulietta Masina, Anthony Quinn, Richard Basehart (Actors)

- Federico Fellini (Director) - Federico Fellini (Writer) - Dino De Laurentiis (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

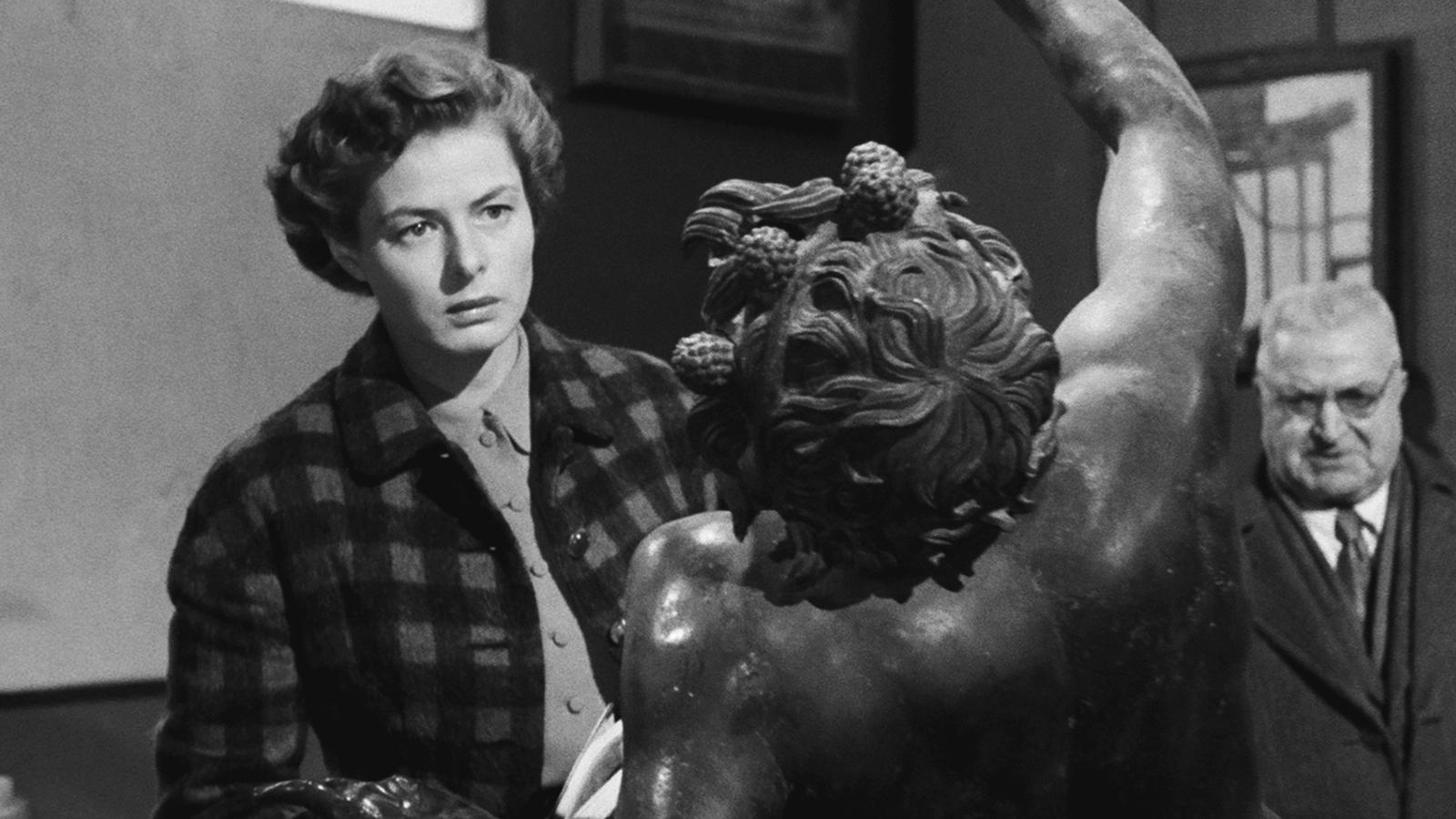

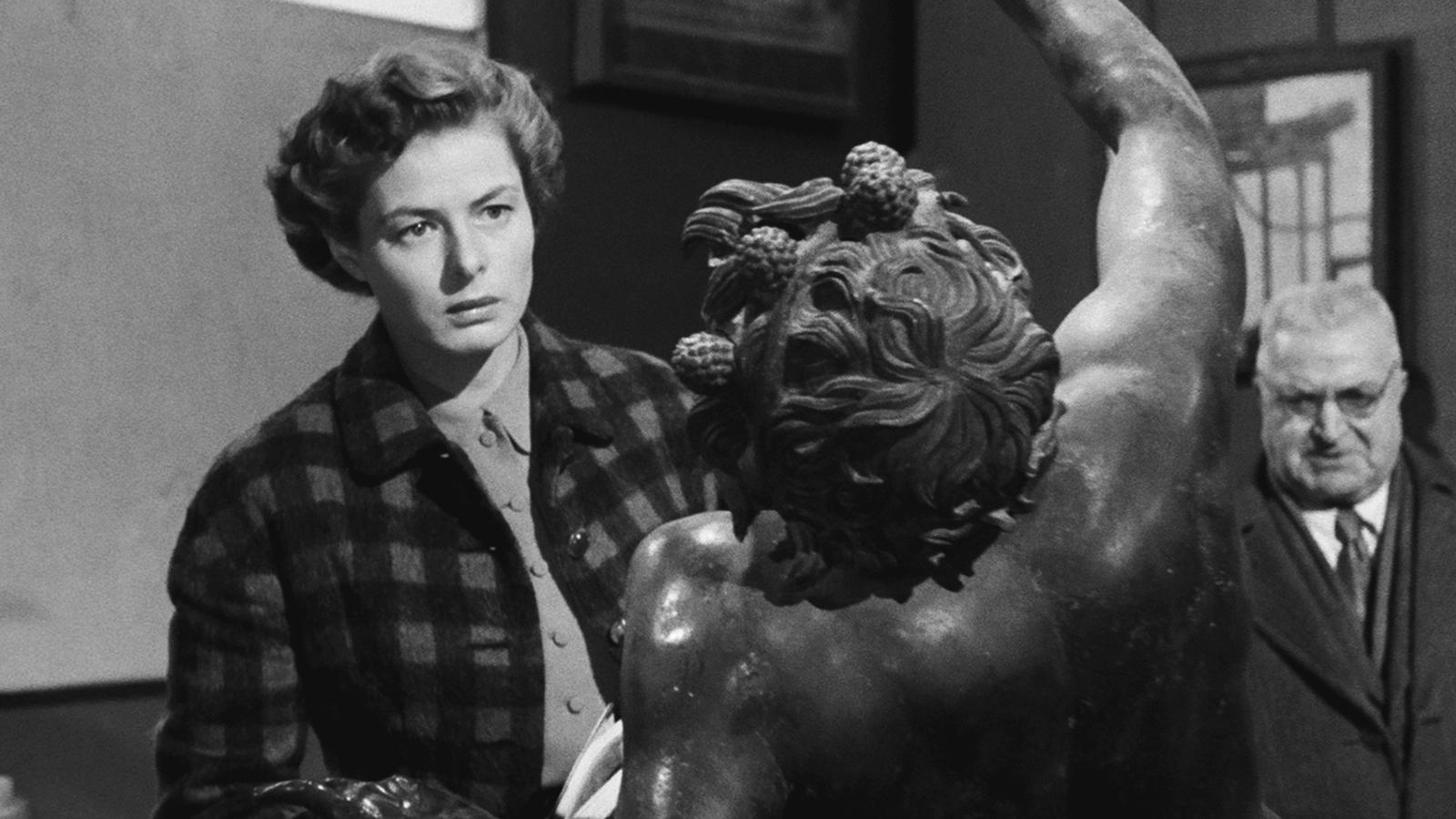

Journey To Italy (1954)

Journey to Italy

1954 • 1h 25min • ★ 7.314/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Ingrid Bergman, George Sanders, Jackie Frost, Maria Mauban, Anna Proclemer

This deceptively simple tale of a bored English couple travelling to Italy to find a buyer for a house inherited from an uncle is transformed by Roberto Rossellini into a passionate story of cruelty and cynicism as their marriage disintegrates around them.

Journey to Italy

1954 • 1h 25min • ★ 7.314/10 • Italy

Directed by: Roberto Rossellini

Cast: Ingrid Bergman, George Sanders, Jackie Frost, Maria Mauban, Anna Proclemer

This deceptively simple tale of a bored English couple travelling to Italy to find a buyer for a house inherited from an uncle is transformed by Roberto Rossellini into a passionate story of cruelty and cynicism as their marriage disintegrates around them.

Among the most influential dramatic works of the postwar era, Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy charts the declining marriage of a couple (Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) from England while on a trip in the countryside near Naples.

More than just an anatomy of a relationship, Rossellini’s masterpiece is a heartrending work of emotion and spirituality.

Considered a predecessor to the existentialist films of Michelangelo Antonioni and hailed as a groundbreaking modernist work by the legendary film journal Cahiers du cinéma.

The film has also been labeled by director Martin Scorsese as one of his favorite films. Journey to Italy is a breathtaking cinematic benchmark.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Ingrid Bergman, George Sanders, Maria Mauban (Actors)

- Roberto Rossellini (Director) - Vitaliano Brancati (Writer) - Roberto Rossellini (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Il tetto (1956)

The Roof

1956 • 1h 37min • ★ 7.4/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Gabriella Pallotta, Giorgio Listuzzi, Gastone Renzelli, Maria Di Rollo, Luciano Pigozzi

Under provincial Italian law at the time, once a roof is erected, the occupants cannot be evicted from a building. This comedy follows the efforts of a family to erect the roof on a house overnight so that a newlywed couple can have their own home.

The Roof

1956 • 1h 37min • ★ 7.4/10 • Italy

Directed by: Vittorio De Sica

Cast: Gabriella Pallotta, Giorgio Listuzzi, Gastone Renzelli, Maria Di Rollo, Luciano Pigozzi

Under provincial Italian law at the time, once a roof is erected, the occupants cannot be evicted from a building. This comedy follows the efforts of a family to erect the roof on a house overnight so that a newlywed couple can have their own home.

Directly after his successful The Gold of Naples (1954), Italian filmmaker Vittorio DeSica served up something of a throwback to his neorealist days.

In The Roof (originally Il Tetto) a pair of young lovers wed in defiance of their families wishes. With the confidence of youth, they decide to set up housekeeping for themselves.

Alas, they soon learn that living on love is virtually impossibility-especially in a postwar economy.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=KUcgos51fMc

The box-office failure of The Roof was a major setback for DeSica’s directorial career: he would not be able to finance another film until the 1960’s Two Women.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Giorgio Listuzzi, Gabriella Pallotta, Luciano Pigozzi (Actors)

- Vittorio De Sica (Director) - Cesare Zavattini (Writer) - Vittorio De Sica (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Rocco and His Brothers (1960)

Rocco and His Brothers

DARING in its realism. STUNNING in its impact. BREATHTAKING in its scope.

1960 • 2h 58min • ★ 8.013/10 • France

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, Katina Paxinou, Alessandra Panaro

When a impoverished widow’s family moves to the big city, two of her five sons become romantic rivals with deadly results.

Rocco and His Brothers

DARING in its realism. STUNNING in its impact. BREATHTAKING in its scope.

1960 • 2h 58min • ★ 8.013/10 • France

Directed by: Luchino Visconti

Cast: Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, Katina Paxinou, Alessandra Panaro

When a impoverished widow’s family moves to the big city, two of her five sons become romantic rivals with deadly results.

Rocco and His Brothers is a 1960 Italian film directed by Luchino Visconti, inspired by an episode from the novel Il ponte della Ghisolfa by Giovanni Testori.

Set in Milan, it tells the story of a migrant family from the South and its disintegration in the society of the industrial North.

The title is a combination of Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers and the name of Rocco Scotellaro, an Italian poet who described the feelings of the peasants of southern Italy.

The film stars Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot, and Claudia Cardinale in one of her early roles before she became internationally known.

The score was composed by Nino Rota.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Alain Delon, Renato Salvatori, Annie Girardot (Actors)

- Luchino Visconti (Director) - Suso Cecchi D'Amico (Writer) - Goffredo Lombardo (Producer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Il posto (1961)

Il Posto

1961 • 1h 38min • ★ 7.66/10 • Italy

Directed by: Ermanno Olmi

Cast: Loredana Detto, Sandro Panseri, Corrado Aprile, Guido Chiti, Tullio Kezich

With his family mired in financial troubles, Domenico moves to Milan, Italy, from his small town to get a job in lieu of furthering his education. A lack of options forces him to take a position as a messenger at a big company, where he hopes to receive a promotion soon. There, Domenico meets Antonietta, a young woman in a similar situation as himself. The two form a tentative relationship, but the soulless nature of their jobs threatens to keep them apart.

Il Posto

1961 • 1h 38min • ★ 7.66/10 • Italy

Directed by: Ermanno Olmi

Cast: Loredana Detto, Sandro Panseri, Corrado Aprile, Guido Chiti, Tullio Kezich

With his family mired in financial troubles, Domenico moves to Milan, Italy, from his small town to get a job in lieu of furthering his education. A lack of options forces him to take a position as a messenger at a big company, where he hopes to receive a promotion soon. There, Domenico meets Antonietta, a young woman in a similar situation as himself. The two form a tentative relationship, but the soulless nature of their jobs threatens to keep them apart.

Coming from a provincial family, Domenico (Sandro Panseri) arrives in Milan in search of a job.

After undergoing a series of absurd physical and psychological tests, he is given the position of a lowly clerk in a corporate firm.

Also applying for a job is Antonietta (Loredana Detto), who becomes the object of shy Domenico’s infatuation.

However, he finds little time to pursue any possible future with her upon starting his new job. The pressures and working hours completely take over his private life.

Domenico, a newcomer in Milan, becomes lonely as a result of these changes and is filled with anxiety over his future.

Il Posto was Ermanno Olmi’s first major work and its achievement was immediately heralded by a prize at the Venice Film Festival.

Drawing influences from neorealism as well as a background making industrial short documentaries, Olmi created a heightened approach to depicting reality.

A miniaturist devoted to the small and seemingly innocuous moments of a man’s life, Olmi’s intimate vision would subsequently influence the works of Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami.

The Impact Of Italian Neorealism

The Italian Neorealist movement had a huge impact on films. They inspired the French New Wave and other types of film styles because they were so unique.

The stories that these directors told in their movies are still relevant in modern times and also changed how people viewed life without censorship or fascist regimes trying to make them think differently.

Italians wanted their voices heard through film, but it was difficult with fascism ruling over Italy at the time.

One thing they did was use non-professional actors, improvised dialogue, location shooting with little set design for an authentic look and feel which translated into authenticity on screen as well as influencing many different genres around the world afterward such as French New Wave.

We can also see Italian Neorealism in the cinema verite films of the 1950s and 1960s.

4 Famous Italian Neorealist Filmmakers

Luchino Visconti

He was famous for his use of location shooting with little set design which translated to authenticity on screen as well as influencing many different genres around the world afterward such as the French New Wave.

His movies were mainly about social classes during fascism in Italy or other topics related to life at this time period like “La Terra Trema” (1948).

Opposition force is seen through Renata who rebels against her father by going out more often than she should have been allowed according to fascist standards and also a character named Lila who has an affair with a

Roberto Rossellini

Rossellini studied law at the University of Rome but left to pursue a career as an actor with some success.

He then became interested in directing movies after seeing Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” (1927).

The movie had such a strong impact that he decided to study filmmaking for three years under Mario Soldati before making his own debut in 1936 with “Paisà”.

His first commercial success came from the 1942 romantic comedy “L’Amore”, which starred Anna Magnani.

Over time, he became more interested in neorealism, a movement that was born after the German occupation of Rome and which advocated for social realism.

Rossellini’s first major neorealist film was “Rome Open City” (1945), followed by Paisà, an adaptation of Luigi Pirandello’s novel about life on an isolated rural estate that had been taken over by local fascists.

Paisà was an international success and paved the way for neorealist films to be seen as art rather than the works of second-rate filmmakers.

Vittorio De Sica

De Sica was born in 1914 to a family of actors. His father, Federico Valeri, had been a member of the Commedia Dell’Arte, and his mother Teresa Parodi-De Sicasessa took on roles as well.

De Sica’s first theatrical experience was as a chorus boy in his parents’ company. His father’s gifts were not passed down to Vittorio, who had an unsettled youth and did poorly at school.

Troops of the Italian Social Republic occupied Rome until 1944; during this time De Sica joined the Italian resistance movement.

In 1946, De Sica became the first Italian film director to win an international award when his neorealistic picture The Bicycle Thief won the prestigious Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival.

De Sica’s career was not limited to cinema; he also directed theatre and television shows as well. He died in 1974 of a heart attack while on holiday with his family in Mexico City.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=YFT5n88A7Sc

Cesare Zavattini

A talented writer, Cesare Zavattini was born in the town of Riesi, Sicily. He wrote for a number of journals including La Sicilia and L’Avvenire d’Italia before his father moved to Milan where he worked as an apprentice electrician at Edison’s factory while studying literature on his own.

In 1919, after serving with the first World War troops stationed in Rome, Zavattini returned to Milan and began writing screenplays for silent films together with Anton Giulio Bragaglia and Mario Bonnard under Domenico Paolella’s direction.

These collaborations led to their association with Angelo Morosoni who founded Cines company which financed production through what became known as the “Morosoni bank.”

Together, Zavattini and Bragaglia created a new style of film that would become known as neorealism.

Their films were less focused on the lavish lifestyle of high society than they were with the lives of those at the bottom – the working class, women, children, and peasants who were often ignored in the escapist dramas of Hollywood.

Zavattini and Bragaglia’s films focused on the human condition, which they saw as being in a continual state of flux, with no moments of rest or permanence.

As with most Italian neorealist films, their characters struggle against economic adversity amid political turmoil that is often brutal and unrelenting.

Which Future Filmmakers Did Italian Neorealism Influence

Neorealism led to filmmakers such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who were inspired by Italian neorealism’s austere style.

The French New Wave film movement of the late 1950s onwards drew heavily on this cinema genre with directors following in De Sica’s footsteps filming stories about children coming into adulthood.

After World War II, many European countries have suffered poverty from their war efforts – France was no exception.

By taking a look at Italy after WWII we can see that they used an artistic form that allowed them to express what it meant to be living under these conditions and how people struggled due to societal forces like corruption or oppressive governments.

Filmmakers such as Ken Loach and John Sayles are often considered Italian Neorealists because they have made many politically charged films like “Kes” (1968) which explores how England’s public education system fails its youth.

And one of the great filmmakers of all time, Martin Scorsese, was hugely influenced by Italian neorealism.

Influential Films Of Italian Neorealism

Italian neorealism reshaped cinema with several groundbreaking films that have stood the test of time.

We’ll jump into a selection of these pivotal works which captured the essence of the movement and left an indelible mark on the film industry.

Bicycle Thieves is perhaps the most iconic example of the neorealist spirit.

Directed by Vittorio De Sica, this 1948 masterpiece showcases the desperate search of a father and his son for a stolen bicycle, which is critical for the father’s job.

The emotional depth and stark social commentary of Bicycle Thieves encapsulate the hardships of post-war Italy.

Another major film, Rome, Open City directed by Roberto Rossellini, pulls us into the grim realities of the Nazi occupation in Rome.

Its vivid portrayal of resistance and oppression laid bare with raw authenticity creates a powerful narrative that’s both deeply personal and broadly societal.

The film not only tells a story of endurance but also ignites a sense of rebellion and hope amidst the darkest of times.

Following are some of the other significant films that suggest the breadth and impact of Italian neorealism:

- Umberto D. – A deeply moving tale of an elderly man fighting to keep his dignity in the face of poverty and social indifference,

- La Terra Trema – Luchino Visconti’s epic portrayal of a Sicilian fishing family’s struggle against exploitation reflects neorealism’s focus on the plight of the disenfranchised,

- Paisan – Rossellini’s six-part anthology illustrates the human condition through varied stories set during the liberation of Italy, again blurring the lines between reality and fiction.

These films not only introduce audiences to the neorealist approach but also provide a lens through which to view the universal human condition.

Each story, rich in detail and nuance, marries the mundane with the monumental, revealing that within the struggles of everyday life, there are larger narratives at play.

In the continuing exploration of Italian neorealism, it’s clear that the influence of these films extends far beyond their immediate post-war context.

Impact And Legacy Of Italian Neorealism

Italian neorealism set the stage for a major shift in global cinema.

We can pinpoint its impact on various fronts – the aesthetic choices filmmakers make, the stories they tell, and the ways in which they engage with issues of social and political relevance.

This movement didn’t just reshape Italian cinema; it had an enduring influence worldwide, inspiring directors to adopt a more realistic and humanistic approach to storytelling.

Filmmakers across the globe drew lessons from the neorealism playbook, integrating its techniques into their own works.

Notably, the French New Wave and the Brazilian Cinema Novo movements both owe a significant debt to Italian neorealism.

Their films reflect the movement’s core principles:

- Authenticity in narrative,

- Emphasis on the human experience,

- A focus on societal issues from a ground-level perspective.

The reverberations of Italian neorealism can still be felt in many of today’s cinematic works.

Films that focus on real-life scenarios, often with a compassionate lens toward their subjects, are carrying the torch of neorealism.

Renowned directors like Martin Scorsese and Satyajit Ray have openly cited neorealism as a foundation for their approach to film, imbuing their own unique stories with the spirit of this transformative movement.

Within the realm of documentary filmmaking, the legacy of Italian neorealism is unmistakable.

The raw, unfiltered glimpse into human conditions and lived experiences championed by neorealists has greatly contributed to the evolution of this genre.

By prioritizing the authentic over the contrived, documentarians continue to mirror the neorealist intention of portraying life as it is, rather than life as cinema traditionally presented it.

What’s clear is that Italian neorealism wasn’t just a post-war phenomenon.

It was a catalyst for change that had far-reaching effects on the very fabric of cinema as an art form.

Through its bold reimagining of film’s potential, neorealism has ensured that its storytelling ethos endures, influencing the way we create and appreciate films long into the future.

What Is Italian Neorealism – Wrap Up

Italian neorealism was undeniably a watershed moment for the art of filmmaking.

We’ve seen how its raw power and authenticity challenged the norms of storytelling, offering a window into the lived experiences of the marginalized.

Its influence echoes through the corridors of global cinema, inspiring a legacy that filmmakers continue to draw upon.

As we reflect on its enduring impact, it’s clear that the neorealist movement didn’t just capture the zeitgeist of post-war Italy, it reshaped our understanding of cinematic expression and the potent role it plays in reflecting societal issues.

Through its innovative spirit, Italian neorealism remains a touchstone for those who believe in the power of film to illuminate truth and provoke thought long after the credits roll.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Italian Neorealism?

Italian Neorealism is a film movement that emerged in Italy after World War II, characterized by stories set amongst the poor and working class, filmed on location, often using non-professional actors.

When Did Italian Neorealism Begin?

Italian Neorealism began in the mid-1940s, after the end of World War II, reflecting Italy’s post-war economic and political climate.

What Are The Main Characteristics Of Italian Neorealism?

The main characteristics include shooting on location, use of non-professional actors, focus on the daily lives of the poor or working class, and themes of justice and human dignity.

How Did Italian Neorealism Influence Global Cinema?

Italian Neorealism influenced global cinema by inspiring movements like the French New Wave and Brazilian Cinema Novo, and by introducing realistic storytelling and location shooting techniques that are still used today.

Can The Legacy Of Italian Neorealism Be Seen In Contemporary Films?

Yes, the legacy of Italian Neorealism can be seen in contemporary films, especially in documentary filmmaking and in movies that focus on social realism and the human condition.

Ready to learn about some other Film Movements or Film History?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

16 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

![Germany Year Zero (DVD) [1948]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51qJ+tJNS6L.jpg)

![The Flowers of St. Francis (The Criterion Collection) [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41pYCdqmQkL.jpg)

I love what you guys are up too. Such clever work and info! Keep up the superb works guys!

Thanks, zovre!

matt what is your full name id like to cite you for my academic paper

It’s Matt Crawford. Thanks, Sharon.

Italian Neorealism is a movement that changed cinema. It was a time when filmmakers were trying to capture the real life experiences of their people. This movement is still going on and is still making a big impact on cinema.

Agree with everything you said.

Italian Neorealism is a movement that changed cinema. It was a time when filmmakers were trying to capture the real life experiences of their people. This movement is still going on and is still making a big impact on cinema.

Thanks.

Fantastic post! I had no idea Italian Neorealism had such a profound impact on the film industry. The way you broke down the movement’s principles and key works was incredibly informative. Thank you for shedding light on this fascinating era in cinema history.

Thanks!

Fascinating read! I had no idea about the significance of Italian Neorealism in the history of cinema. The emphasis on everyday life and social issues really resonates with me as a viewer. The way the movement challenged traditional cinema and paved the way for new storytelling approaches is truly inspiring. Can’t wait to explore more of this era’s films!

Really means a lot—thanks for commenting!

A fascinating read! I had no idea Italian Neorealism had such a significant impact on the film industry. The movement’s focus on social realism and the use of non-professional actors really resonated with me. It’s amazing to see how a group of filmmakers could challenge the status quo and create something truly innovative and influential.

Really appreciate your comment! Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

Wow, I had no idea about the impact of Italian Neorealism on the film industry. The way you explained the movement and its influence on the cinematography was really insightful. I especially appreciated the inclusion of specific examples from films like ‘Bicycle Thieves’ and ‘Rome Open City’. I’ll definitely be checking out more of these classics now!

Thanks! What’s your take on this topic?