- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

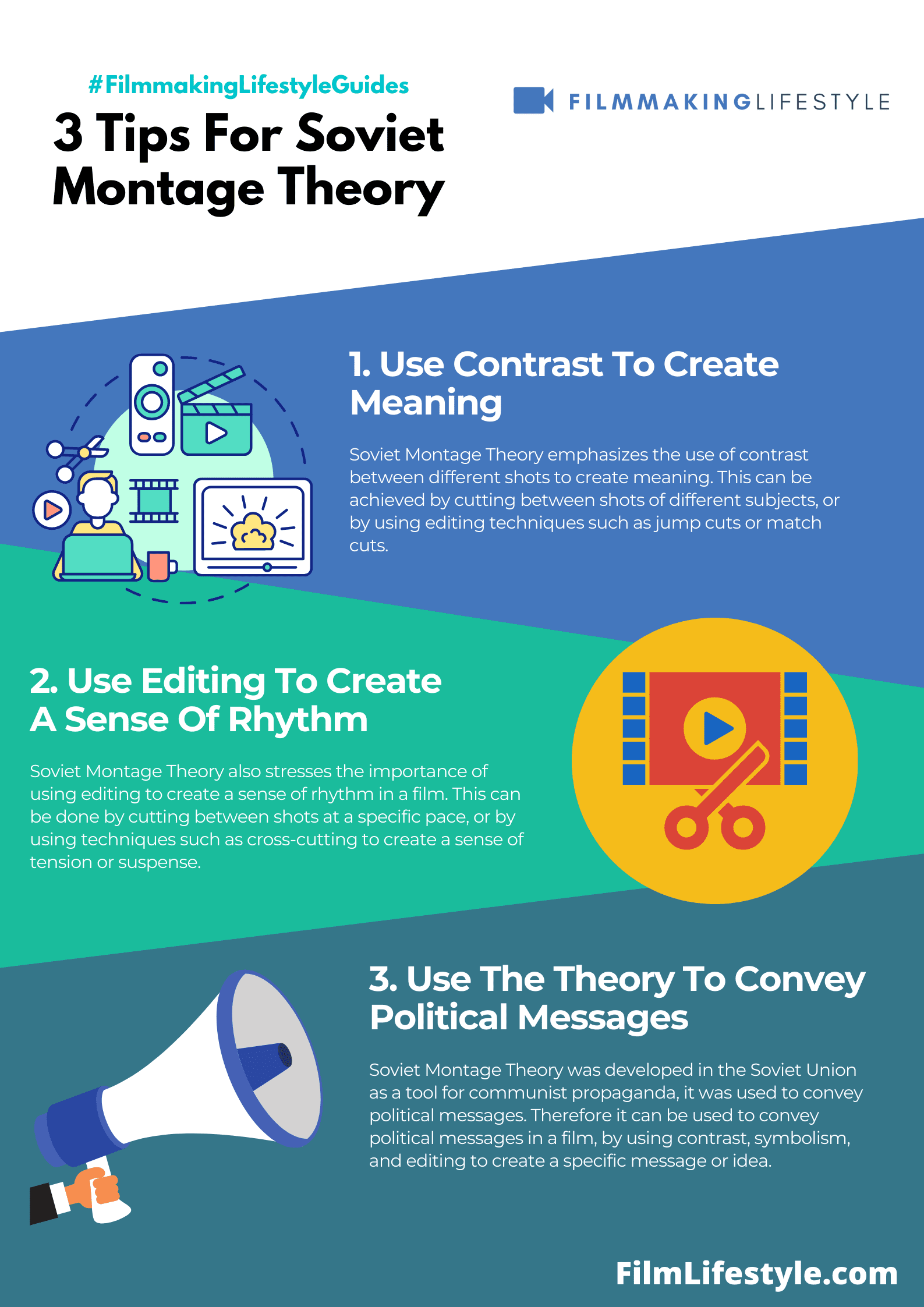

Soviet Montage Theory revolutionized the way we understand film editing.

It’s not just about splicing scenes together; it’s an art form that evokes emotions and conveys messages in a powerful, unique way.

We’ll explore how this theory emerged in the 1920s Soviet Union and why it still influences filmmakers today.

Get ready to dive deep into the world of montage and discover how it shapes the stories we see on the big screen.

SOVIET MONTAGE THEORY

What Is Soviet Montage Theory?

Soviet montage theory is a cinematic theory that was developed by Sergei Eisenstein.

It’s based around an editing technique that uses juxtaposition to create meaning, and it can be used in film or literature.

The idea behind this theory is that if two images are put together on screen with no explanation of how they connect, the audience will make up their own story about what happened between them and fill in the gaps.

Origins Of Soviet Montage Theory

The roots of Soviet Montage Theory take us back to the political upheaval and revolutionary spirit of early 20th century Russia.

After the 1917 October Revolution, the newly established Soviet government recognized the potential of cinema as a tool for education and ideological dissemination.

It was during this time that visionary directors like Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov began experimenting with the medium.

Kuleshov’s groundbreaking work in film editing led to what is now known as the Kuleshov Effect – the understanding that the meaning in motion pictures is often dictated more by the editing than by the content of the individual shots.

Eisenstein, often considered the father of montage, believed that collision and conflict of images could exploit the emotional responses of audiences.

He put this theory into practice in films such as Battleship Potemkin and October: Ten Days That Shook the World.

These works not only displayed but honed the craft and effectiveness of montage.

Key Features of Soviet Montage Theory:

- Emphasis on editing over cinematography,

- Use of juxtaposition to generate meaning,

- Conflict as a catalyst for emotional response.

The bold explorations of these filmmakers not only defined an era of Soviet cinema but also left a stamp on the film industry worldwide.

As narrative tools, their techniques remain influential, shaping the way stories are told and experienced on the big screen.

Understanding Montage

Montage, in the realm of film, is a powerful storytelling technique that involves the editing together of different shots to create a new meaning that no single shot can offer on its own.

It’s this synthesis of imagery that stands at the heart of Soviet Montage Theory, transforming raw footage into a dynamic narrative force.

Through the artful combination of shots, filmmakers can suggest associations and provoke emotional reactions not inherently present in individual frames.

The juxtaposition of contrasting images – a technique integral to Montage Theory – can result in a heightened emotional impact or a sophisticated commentary that resonates with the audience.

- Key concepts in montage include – Juxtaposition – Rhythm – Symbolism – Conflict – Intellectual Context.

By understanding and employing these elements, directors can choreograph the viewer’s experience, using the interplay of visuals to guide emotions and intellect.

Films like Battleship Potemkin and October: Ten Days That Shook the World stand as quintessential examples where montage propels the narrative and manipulates audience perceptions.

The essence of Montage Theory lies not only in the visual and emotional impact but also in its revolutionary spirit.

It’s a defiant rejection of traditional continuity editing, opting instead for a fragmented and often collision-based approach.

This method emphasizes the importance of the edit over the individual shot, suggesting that the true power of cinema is in its capacity to assemble disparate elements into a compelling whole.

The Principles Of Soviet Montage Theory

Understanding Soviet Montage Theory involves delving into its foundational principles which are as dynamic and complex as cinema itself.

These principles are not just a set of rules but rather a framework to provoke thought, emotion, and a revolutionary form of expression.

At the core of these principles lies the idea of conflict.

Different types of conflicts can arise through montage, such as:

- Spatial conflict – where the contrast between shots emphasizes the distance or closeness of objects.

- Temporal conflict – which pits different timelines against each other, creating a sense of disorientation or revelation.

- Graphic conflict – which arises from the juxtaposition of visual elements, often creating a stark visual contrast or symbolic meaning.

- Emotional conflict – that provokes a response from the audience by clashing disparate emotional cues.

Rhythm plays a pivotal role, as the length of shots can dramatically affect the pace and feel of a film.

Films like Battleship Potemkin and Man with a Movie Camera exemplify the use of rhythmic editing to synchronize the viewer’s response with the intended message of the sequence.

Symbolism within Soviet Montage Theory goes beyond mere resemblance, tapping into deeper societal undercurrents.

The principle holds that the symbolic use of objects, characters, or settings in a montage sequence conveys complex ideas that resonate with the social and political landscapes.

The theory also places a significant emphasis on the intellectual context – the idea that through montage, films can encourage viewers to discern intellectual connections.

This principle strives for an active audience, one that engages with the film’s ideas and its societal critique.

By examining the principles of Soviet Montage Theory, we’re not only uncovering the mechanics of a revolutionary cinematic language but also gaining insight into a powerful form of socio-political commentary that continues to influence filmmakers around the world.

Best Soviet Montage Films

The filmmakers wanted to show what life was really like at this time by using editing techniques such as quick cuts between different scenes without any narration or dialogue.

They did not think about whether people would be offended by seeing violence or sex on screen because they thought it would help audiences understand their lives more deeply.

In Soviet montage films, artists use various editing techniques to create a story that is often uplifting and hopeful.

These films are not just great sources of entertainment; they also provide important cultural insight into the history of the USSR and its people.

Let’s dive into our list of the best Sovie Montage films.

Kino-Eye (1924)

Kino-Eye is a film made by the Soviet director Dziga Vertov. It was his first documentary and only silent film, filmed in 1924.

The word Kino-eye means “cinema eye” or “film camera”. In this innovative work of cinema,

Vertov uses different shots to show how all areas of life are captured on film.”

The documentary shows many aspects of Russian life such as food production, children playing, and farmers at work.

Overall it is a very interesting piece that captures the reality of everyday life through an unusual perspective.

Kino-Eye explores these ideas by presenting different types of images that show different ways one can view reality: from realism to abstractionism, right down to pure abstractions.

It also reflects on the nature of modernity, specifically during World War I with its rapid changes and innovations while exploring how other cultures have reacted accordingly throughout history.

This new style of filmmaking allowed the audience to see more than just one shot on screen at once – it explored different angles with camera movements and editing techniques.

It also focused on how human beings react in front of cameras which helped directors understand how their actors should act for filming.

Kino-eye has been referenced by many famous directors including Alfred Hitchcock who said “Years ago I realized that if you want to scare someone out of their wits then show them something absolutely ordinary.”

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Dziga Vertov (Actor)

- Dziga Vertov (Director) - Dziga Vertov (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924)

The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks is a 1924 comedy film by Soviet director Lev Kuleshov.

It is notable as the first Soviet film that explicitly challenges American stereotypes about Soviet Russia.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Porfiry Podobed, Boris Barnet, Aleksandra Khokhlova (Actors)

- Lev Kuleshov (Director) - Nikolay Aseev (Writer)

- English (Playback Language)

- English (Subtitle)

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

Battleship Potemkin has long been considered one of the most influential films ever made because it introduced a new form of art that combined documentary-style realism with montage editing techniques that had never before been seen.

This revolutionary style influenced other filmmakers around the world including Hollywood directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Akira Kurosawa.

Battleship Potemkin is an important film because it documents these events and gives insight into how things got so bad.

Although this film was made more than 90 years ago, it is still relevant today because many people are not educated about the events that took place during this time period or about what happened to those who fought for change.

Eisenstein’s use of editing and cinematography help tell an emotional story while educating viewers about historical facts.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Aleksandr Antonov, Vladimir Barsky, Grigorio Aleksandrov (Actors)

- Sergei M. Eisenstein (Director) - Nina Agadzhanova (Writer) - Jacob Bliokh (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

The Death Ray (1925)

The Death Ray is a 1925 Soviet science fiction film directed by Lev Kuleshov.

The first and last reels of the film have been lost. This film ran at 2 hours, 5 minutes, making this one of the earliest full-length science fiction films.

Despite the fact that many sources claim the inspiration for the film to be the novel The Garin Death Ray by Aleksei Tolstoy, this is not the case. It is impossible since the book was published two years after the film, in 1927.

Furthermore, the film has many similarities with a book by Valentin Kataev, called Lord of Iron, published in 1924.

Moreover, the theme of death rays was very popular at the time because of the 1923 claim of British inventor Harry Grindell Matthews to have created a “death ray”.

Strike (1925)

The film “Strike” (1925) is a silent movie that portrays the struggles of coal miners. It was directed by Sergei Eisenstein.

The film depicts the workers in their fight for better work conditions against an oppressive capitalist society.

There are two main themes that are portrayed throughout this movie: human solidarity versus individualism, as well as social change versus reformism.

These two concepts are shown through many aspects of the film including how the characters interact with one another, how they react to changing circumstances around them, and what type of actions they take to try to make changes in their world.

The 1920s were a time when workers were fighting for better wages, safer working conditions, and more rights in general.

This struggle culminated in what became known as “the great steel strike,” which began on September 22nd, 1919.

Eisenstein documented this momentous event in his own way – through film.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Maksim Shtraukh, Grigori Aleksandrov, Mikhail Gomorov (Actors)

- Sergei Eisenstein (Director) - Grigori Aleksandrov (Writer) - Boris Mikhin (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Mother (1926)

Mother is a 1926 Soviet drama film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin. It depicts the radicalization of a mother, during the Russian Revolution of 1905, after her husband is killed and her son is imprisoned.

Based on the 1906 novel The Mother by Maxim Gorky, it is the first installment in Pudovkin’s “revolutionary trilogy”, alongside The End of St. Petersburg (1927) and Storm Over Asia (aka The Heir to Genghis Khan) (1928).

The Devil’s Wheel (1926)

The Devil’s Wheel is a 1926 Soviet silent crime film directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg.

During a walk in the garden of the People’s House, sailor Ivan Shorin meets Valya and, having missed the scheduled time is late for the ship which is departing for a cruise.

The next morning he has to go on a distant foreign trek and his slight delay has turned into desertion. The young people are sheltered by artists who turn out to be ordinary punks.

Not wanting to become a thief, Ivan runs away and surrenders himself to the authorities. After the trial of his friends and just punishment, he returns to his former life.

The Overcoat (1926)

The Overcoat is a 1926 Soviet drama film directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, based on the Nikolai Gogol stories “Nevsky Prospekt” and “The Overcoat”.

Charlie Chaplin was invited to play the lead role, but as an alien resident in the United States, was threatened by US government officials with being refused entry back into the country if he made the film and it contained Soviet propaganda.

Arriving in St. Petersburg, landowner Ptitsin (Nikolai Gorodnichev) tries to achieve with the help of bribes a favorable decision of his litigation concerning a neighbor.

With swindler and blackmailer Yaryzhka (Sergei Gerasimov) he finds a functionary who is willing to take the money.

Cautious Bashmachkin (Andrei Kostrichkin) to whom the briber comes, does not want to take on the dangerous enterprise, although he can not resist the charms of a beautiful female stranger (Antonina Eremeeva) whom he met on the Nevsky Prospekt.

Later Akaky Akakievich finds out that the woman of his dreams is only an accomplice to swindlers.

Fearing punishment, the frightened bureaucrat becomes even more reclusive, all the more carefully isolating himself off from people.

The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

The End of St. Petersburg is a 1927 silent film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin and produced by Mezhrabpom.

Commissioned to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the October Revolution, The End of St Petersburg was to be one of Pudovkin’s most famous films and secured his place as one of the foremost Soviet montage film directors.

The film forms part of Pudovkin’s ‘revolutionary trilogy’, alongside Mother (1926) and Storm Over Asia (aka The Heir to Genghis Khan) (1928).

The End of St. Petersburg is a political film, explaining why and how the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917.

The film covers the period from about 1913 to 1917. The film does not show the political figures of the time. The emphasis is on the struggle of ordinary people for their rights and for peace against the power of capital and the autocracy.

The film inspired the composer Vernon Duke to write his eponymous oratorio (completed in 1937).

A simple peasant boy arrives in St. Petersburg to obtain employment. Fate leads him to a factory where there are severe, almost slave-like working conditions.

He unwittingly helps in the arrest of an old village friend who is now a labor leader. He attempts to fix his wrongdoing but ends up in a fight and then arrested.

His punishment is being sent to fight in World War I. After three years, he returns ready for revolution.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Aleksandr Chistyakov, Vera Baranovskaya, Vasili Kovrigin (Actors)

- V.I. Pudovkin (Director) - Nathan Zarkhi (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

The House On Trubnaya (1928)

The House on Trubnaya is a comedy film directed by Boris Barnet and starring Vera Maretskaya.

The film is set in Moscow at the height of the NEP. The petty-bourgeois public carries out their philistine life full of bustle and gossip in the house on the Trubnaya Street.

One of the tenants, Mr. Golikov (Vladimir Fogel), owner of a hairdressing salon, is looking for a housekeeper who is modest, hard-working and non-union.

A suitable candidate for use seems to him a country girl nicknamed Paranya, full name Praskovya Pitunova (Vera Maretskaya).

Soon the house on Trubnaya receives shocking news that Praskovya Pitunova is elected deputy of the Mossovet by the maids’ Trade Union.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Vladimir Fogel, Yelena Tyapkina, Aleksandr Gromov (Actors)

- Boris Barnet (Director) - Nikolai Erdman (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Your Acquaintance (1927)

Your Acquaintance is a 1927 Soviet short silent drama film directed by Lev Kuleshov and starring Aleksandra Khokhlova, Pyotr Galadzhev and Yuri Vasilchikov.

Only a fragment of the film still survives.

The film’s art direction was by Vasili Rakhals and Alexander Rodchenko.

The film is set in Moscow, during the years of the NEP. Journalist Khokhlova falls in love with Petrovsky, a responsible officer at an industrial plant.

This infatuation has a negative impact on her work and the girl is fired. Meanwhile Petrovsky’s wife returns.

This situation reveals the true nature of the lover who is an egoist and a vulgarian.

The girl is near suicide however the tragic denouement is prevented by Vasilchikov who has been in love with the journalist for a long time, a modest editor of the department “Working inventions.”

Moscow in October (1927)

Moscow in October is a Soviet silent historical drama film directed by Boris Barnet.

The picture fared poorly at the box-office and with the critics. The film has been partially lost.

The film is timed to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution and was withdrawn by order of the “October Jubilee Commission” under the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR.

The Diplomatic Pouch (1927)

The Diplomatic Pouch is a 1927 Soviet silent thriller film directed by Alexander Dovzhenko. The first two parts of the film are lost.

The film’s plot is based on the real murder of the Soviet diplomatic courier Theodor Nette abroad.

The pouch of the Soviet diplomat, which is stolen by British spies, is taken away by the sailors of a ship sailing to Leningrad who deliver it to the authorities. The intelligence agents make every effort to retrieve the bag.

Zvenigora (1927)

Zvenigora is an early Soviet silent film directed by Alexander Dovzhenko and considered one of the most significant examples of Ukrainian cinema, notable for its innovative cinematic technique.

Zvenigora is a silent film by director Alexander Dovzhenko. It depicts the life of early 20th century peasants in Ukraine, with a focus on their resistance to collectivization.

The movie is shot largely outdoors and features some of the most beautiful Ukrainian landscapes ever captured on film.

- DVD-R

- ALL Region

- North American NTSC Standard

- Language: English subtitles - Orchestra music score

- Studio: Grapevine Video

The Club of the Big Deed (1927)

The Club of the Big Deed or The Union of a Great Cause is a 1927 Soviet silent historical drama film directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg.

The film is about the 1825 Decembrist revolt.

Storm Over Asia (1928)

Storm over Asia is a Soviet propaganda film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin, written by Osip Brik and Ivan Novokshonov, and starring Valéry Inkijinoff.

It is the final film in Pudovkin’s “revolutionary trilogy”, alongside Mother (1926) and The End of St. Petersburg (1927).

In 1918 a young and simple Mongol herdsman and trapper is cheated out of a valuable fox fur by a European capitalist fur trader.

Ostracized from the trading post, he escapes to the hills after brawling with the trader who cheated him.

In 1920 he becomes a Soviet partisan and helps the partisans fight for the Soviets against the occupying British army.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Valeri Inkishanov, Anel Sudakevich, I. Dedintsev (Actors)

- V.I. Pudovkin (Director) - Osip Brik (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

October: Ten Days That Shook the World (1928)

October: Ten Days That Shook the World is a Soviet silent historical film by Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov.

It is a celebratory dramatization of the 1917 October Revolution commissioned for the tenth anniversary of the event.

Originally released in the Soviet Union as October, the film was re-edited and released internationally as Ten Days That Shook The World, after John Reed’s popular 1919 book on the Revolution.

The film opens with the elation after the February Revolution and the establishment of the Provisional Government, depicting the throwing down of the Tsar’s monument.

It moves quickly to point out it’s the “same old story” of war and hunger under the Provisional Government, however.

The buildup to the October Revolution is dramatized with intertitles marking the dates of events.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Vladimir Popov, Vasili Nikandrov, Layaschenko (Actors)

- Sergei Eisenstein (Director) - Grigori Aleksandrov (Writer) - Arkadiy Alekseyev (Producer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Lace (1928)

Lace is a 1928 Soviet silent film directed by Sergei Yutkevich and starring Nina Shaternikova, Konstantin Gradopolov, and Boris Tenin.

The film is based on the story “Wall-news” written by Mark Kolosov.

Komsomol members of a lace factory release their own wall newspaper. Senka the artist draws caricatures of local hooligans, the leader of whom is Petya Vesnukhin. Activist Marusja tries to get Petya out of bad company.

The New Babylon (1929)

The New Babylon is a silent historical drama film written and directed by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg.

The film deals with the 1871 Paris Commune and the events leading to it, and follows the encounter and tragic fate of two lovers separated by the barricades of the Commune.

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his first film score for this movie. In the fifth reel of the score he quotes the revolutionary anthem, “La Marseillaise” (representing the Commune), juxtaposed contrapuntally with the famous “Can-can” from Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld.

Footage from The New Babylon was included in Guy Debord’s feature film The Society of the Spectacle (1973).

Kozintsev and Trauberg found some of their inspiration in Karl Marx’s The Civil War in France and The Class Struggle in France, 1848-50.

My Grandmother (1929)

In a nameless, drab office building, Soviet workers push paper, waste time, and do everything to make their government as inefficient as possible.

A bureaucrat (A. Takaishvili) has just been fired for his improper, wasteful working methods, and his wife (Bella Chernova) is furious at him.

He quickly learns that he can procure a new job with help of a sponsor.

As the bureaucrat and his doorman (E. Ovanov) discuss how to go about his search, his wife becomes increasingly unhinged.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Aleqsandre Takaishvili, Bella Chernova, E. Ovanov (Actors)

- Kote Mikaberidze (Director) - Giorgi Mdivani (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Arsenal (1929)

Arsenal is a Soviet war film by Ukrainian director Alexander Dovzhenko.

The film was shot at Odessa Film Factory of VUFKU with the camera of legendary cameraman Danyl Demutskyi and using the original sets made by Volodymyr Muller.

The expressionist imagery, perfect camera work and original drama took the film far beyond the usual propaganda and made it one of the most important pieces of Ukrainian avant-garde cinema. The film was made in 1928 and released early in 1929.

It is the second film in his “Ukraine Trilogy”, the first being Zvenigora (1928) and the third being Earth (1930).

The film concerns an episode in the Russian Civil War in 1918 in which the Kiev Arsenal January Uprising of workers aided the besieging Bolshevik army against the Ukrainian national Parliament Central Rada who held legal power in Ukraine at the time.

Regarded by film scholar Vance Kepley, Jr. as “one of the few Soviet political films which seems even to cast doubt on the morality of violent retribution”, Dovzhenko’s eye for wartime absurdities (for example, an attack on an empty trench) anticipates later pacifist sentiments in films by Jean Renoir and Stanley Kubrick.

Man With a Movie Camera (1929)

Cinematography is a fascinating art. Some of the earliest films were created by Georges Méliès, who was fascinated with the new technology and would experiment with all sorts of trickery to create illusions on screen.

A man named Dziga Vertov became interested in film as well and started documenting his life through filmmaking.

One of his most famous documentaries is called Man With A Movie Camera (1929). This documentary features footage from around Moscow and Kiev as it follows citizens going about their daily lives.

However, what makes this documentary so unique is that Vertov also experimented with different camera angles and techniques in order to capture more than just traditional shots.

He wanted to give viewers an immersive experience they couldn’t get through other artistic means.

The movie captures everyday life in Moscow from street corners to markets. It has been hailed as an important work of Russian cinema and has had a lasting effect not only on filmmaking but also photography.

In this documentary, Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov uses a camera to show the world how man creates an illusion of reality through editing.

The film experiments with editing techniques that would go on to influence the growth of cinema and are still used today in Hollywood blockbusters. It also captures daily life in early 20th century Russia like no other movie before it had done.

- Polish Release, cover may contain Polish text/markings. The disk has English subtitles.

- English (Subtitle)

Earth (1930)

Earth is a Soviet film by Ukrainian director Alexander Dovzhenko, concerning the process of collectivization and the hostility of Kulak landowners under the First Five-Year Plan.

It is Part 3 of Dovzhenko’s “Ukraine Trilogy” (along with Zvenigora and Arsenal). It was released in the U.S. in 1930 with the title Soil.

Earth is commonly regarded as Dovzhenko’s masterpiece. The film was voted number 10 on the prestigious Brussels 12 list at the 1958 World Expo.

Alone (1931)

Alone is a Soviet film released in 1931. It was written and directed by Leonid Trauberg and Grigori Kozintsev.

It was originally planned as a silent film, but it was eventually released with a soundtrack comprising sound effects, some dialogue (recorded after the filming) and a full orchestral score by Dmitri Shostakovich.

The film, about a young teacher sent to work in Siberia, is in a realist mode and addresses three political topics then current: education, technology, and the elimination of the kulaks.

Golden Mountains (1931)

Golden Mountains is a Soviet silent drama film directed by Sergei Yutkevich.

A re-edited sound version of the film was released in 1936.

A Simple Case (1932)

A Simple Case is a 1932 Soviet film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin and Mikhail Doller.

Deserter (1933)

The Deserter is a Soviet drama film directed by Vsevolod Pudovkin.

It was his first sound picture.

- Amazon Prime Video (Video on Demand)

- Boris Livanov, Vasili Kovrigin, Aleksandr Chistyakov (Actors)

- Vsevolod Pudovkin (Director) - Nina Agadzhanova (Writer)

- (Playback Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

The Impact Of Soviet Montage Theory On Filmmaking

The influence of Soviet Montage Theory on filmmaking extends far beyond its historical period and geographical origin.

Its revolutionary approach has become a universal language in cinema that directors and editors across the globe still use to craft compelling narratives.

We’ve witnessed the theory’s principles engender a new dimension of cinematic expression.

One critical aspect of this influence can be seen in editing techniques, where quick cuts and jarring transitions became tools for filmmakers—a stark contrast to the continuity editing that preceded it.

Films such as Battleship Potemkin and Man with a Movie Camera showcased these tactics, prompting international filmmakers to experiment with temporal and spatial manipulation.

Not only did montage influence individual films, but it also played a pivotal role in shaping entire film movements.

Movements such as the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism owe a debt to Soviet Montage for challenging narrative norms and reflecting societal changes.

Here we see montage theory’s underlying ethos – to evoke emotions and provoke thoughts – driving filmmakers to push boundaries:

- Exploring unconventional narrative structures,

- Utilizing visual metaphors and symbols,

- Engendering audience introspection.

We see montage theory’s legacy in modern film practices as well.

It has become foundational in the teaching of film theory and analysis, underscoring the power of editing in shaping a film’s pace and message.

also, contemporary directors often cite montage as an influence in their work, ensuring the theory remains relevant in an ever-evolving industry.

The rhetorical power of montage continues to resonate, cultivating an environment where film is not just entertainment but also a medium for cultural and political discourse.

It reminds us that film can be a potent tool for reflection and change, inspiring new generations to consider the implications of image and sound in storytelling.

Contemporary Examples Of Montage In Film

In the realm of modern cinema, the echoes of Soviet Montage Theory are unmistakable.

Filmmakers continue to use montage as a dynamic tool for storytelling and emotional impact.

Take Christopher Nolan’s Inception – the film’s climactic sequence is a masterful display of parallel editing, a technique central to montage.

It interweaves multiple layers of action, each with different temporal dynamics, to intensify the viewer’s experience of suspense and urgency.

While the principles of montage are embedded in the DNA of film editing, certain works stand out for their innovative use of this technique.

Requiem for a Dream by Darren Aronofsky showcases a hyperkinetic form of montage.

This accelerates the narrative pace and plunges the audience into the characters’ fractured psyches.

Similarly, City of God employs a frenetic editing style that reflects the chaotic environment of the film’s setting, drawing the viewer deep into the visceral reality of the favelas.

We observe that montage has transcended traditional boundaries and found a place in various genres and formats:

- In documentaries, montage helps to construct a compelling argument or evoke a strong emotional response.

- Music videos frequently rely on montage to create a rhythmic visual flair that complements the audio track.

- Even in video games, montage is utilized to develop narrative exposition and to enhance the player’s immersion in the game world.

These examples affirm that the influence of montage extends far beyond the films of the early Soviet era.

Today’s directors leverage its power to achieve a wide spectrum of artistic and communicative objectives, ensuring that this pioneering editing technique remains as relevant and revolutionary as it was almost a century ago.

What Is Soviet Montage Theory – Wrap Up

We’ve seen the enduring impact of Soviet Montage Theory on the landscape of visual storytelling.

Its principles continue to resonate, shaping how we perceive and craft narratives across various media.

From the gripping sequences in Inception to the raw cuts of City of God, montage remains a potent force in evoking deep responses from audiences worldwide.

As we explore new horizons in film and beyond, it’s clear that the revolutionary ideas born from early Soviet filmmakers will persist, inspiring us to think critically about the images we see and the stories we tell.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Soviet Montage Theory?

Soviet Montage Theory is a film editing approach developed in the 1920s by Soviet filmmakers.

It emphasizes the editing of separate shots to create unique meanings and emotional responses, different from what each shot would convey individually.

How Has Soviet Montage Theory Influenced Modern Filmmaking?

The theory has significantly influenced modern filmmaking, informing directors and editors’ choices in creating narratives.

Its principles are evident in various film movements and individual works, such as those from Christopher Nolan and Darren Aronofsky.

Can You Name Some Films That Showcase The Principles Of Montage Theory?

Examples of films utilizing Montage Theory include Christopher Nolan’s Inception, Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream, and City of God, which demonstrate the power of montage in storytelling and emotional impact.

Is Montage Theory Relevant To Other Forms Of Media Outside Of Traditional Film?

Yes, montage is a dynamic tool that is also relevant in documentaries, music videos, and even video games, proving that its influence extends into various forms of modern media beyond traditional filmmaking.

What Cultural Impact Does Montage Theory Have?

Montage Theory has a profound cultural impact as it turns film into a medium for cultural and political discourse.

By provoking thoughts and emotions through edited images, it allows cinema to comment on societal issues and human experiences.

Ready to learn about more Film History & Film Movements?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

1 Comment

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

![Man with a Movie Camera (and other works by Dziga Vertov) (1929) [Masters of Cinema] 2-Disc Blu-ray edition](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51NuWeao8QL.jpg)

I love this era of filmmaking. Thanks for information on what the Soviets were doing back then.