- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

Soviet Parallel Cinema emerged as an underground film movement, challenging the norms of traditional Soviet filmmaking.

It’s a intriguing realm where directors defied state censorship to create art that was true to their visions.

We’ll jump into the heart of this cinematic rebellion, exploring how these films were made and why they remain influential today.

Stay with us as we uncover the secrets of Soviet Parallel Cinema, a bold expression of creativity in the face of conformity.

Soviet Parallel Cinema

What Is Soviet Parallel Cinema?

Soviet Parallel Cinema was an underground film movement in the Soviet Union during the 1980s.

It operated parallel to the state-controlled cinema industry and was characterized by its experimental style, personal expression, and often critical stance towards Soviet society.

Filmmakers in this movement worked outside the official state-run film industry, creating films that were more artistic and avant-garde, often exploring themes of individualism, existentialism, and social commentary.

Origins Of Soviet Parallel Cinema

The roots of Soviet Parallel Cinema can be traced back to the early 1960s.

This was a period of relative thaw in the Soviet Union’s strict cultural policies – a brief window that allowed a new generation of filmmakers to experiment and express their artistic vision.

As students at state-run institutions like the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), these budding directors began to challenge the rigid frameworks of Socialist Realism that dominated the Soviet film industry.

In contrast to the epic spectacles that were encouraged by the state, Soviet Parallel Cinema was intensely personal and stylistically diverse.

Films of this movement often delved into the psyche of individual characters and explored taboo subjects.

Our examination of this history reveals several key features:

- The use of allegory and metaphor to circumvent censorship,

- A focus on the existential struggles of the characters,

- The embrace of poetic and nonlinear narratives.

The influence of Western filmmakers, including those from the French New Wave, was evident in the works of Soviet Parallel Cinema.

Yet Even though the restrictions, these Soviet directors managed to create a unique cinematic language that broke away from the official propaganda.

Films such as The Color of Pomegranates and Andrei Rublev, helmed by Sergei Parajanov and Andrei Tarkovsky respectively, stood as rebellious icons that defied the conformist cultural landscape.

This period of prolific, albeit underground, creativity set the stage for a formal recognition of the movement.

While the films themselves were seldom seen by the public due to strict state control over distribution, their impact resonated through the participation in clandestine viewings and the spread of samizdat – the underground publication of banned texts and materials.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Soviet Parallel Cinema film movement, check out our in-depth profile and explore our comprehensive timeline of film movements to see where it fits in cinema history.

The legacy of Soviet Parallel Cinema lives on, highlighting the resilience of artistic spirit in oppressive circumstances and its impact on filmmaking as a form of socio-political commentary.

Defying State Censorship

In the heart of the Soviet Union’s tightly controlled film industry, filmmakers of the Soviet Parallel Cinema movement covertly broke through the iron curtain of censorship.

Crafting stories that slipped past the watchful eyes of state reviewers, these directors used subversive symbolism and layered narratives to voice their dissent.

Andrei Rublev and The Color of Pomegranates stood not only as works of art but as bold statements against the repression of free expression.

They often sidestepped the pervasive censorship through several clever tactics:

- Utilizing ambiguous allegory and metaphor,

- Embedding political commentary in historical or mythical contexts,

- Minimizing dialogue to evade textual scrutiny.

These methods allowed them to explore themes of spirituality, existentialism, and personal freedom.

The films’ multifaceted characters, complex storylines, and abstract imagery required a deeper level of engagement from viewers, urging them to read between the lines of what was outwardly presented on the screen.

Authorities often misinterpreted the films’ true intentions due to their enigmatic nature, allowing some projects to be green-lit for production.

Yet, even with the approval, these films encountered numerous obstacles from initial shooting to their final cut.

The Mirror, for instance, faced challenges right from the start but eventually overcame them through the resilience and creativity of its creators.

This era of filmmaking was not only about the final product but also about the process – a continuous struggle between the artist’s vision and the state’s ideology.

Each film bore the mark of this conflict, embodying the courage it took to bring these stories to life amidst a culture of silence and repression.

Themes And Styles In Soviet Parallel Cinema

Exploring the profound narrative layers within Soviet Parallel Cinema reveals a nuanced tapestry of themes and styles.

These films often challenged viewers with their deep allegorical significance and rich symbolism.

Our examination uncovers central motifs such as:

- Inward exploration of the human spirit,

- Constructs of existential crises,

- Underlying tones of political and social dissent.

Directors within this movement crafted their works to not only entertain but also provoke thought and dialogue.

This was no small Try during the Soviet era, where every form of art was meticulously scrutinized by the state.

The subtlety in dialogue and performance artistry was key since overt expression could lead to censorship or worse.

When considering styles, the filmmakers of Soviet Parallel Cinema favored a distinct aesthetic approach that further distanced their work from mainstream Soviet filmmaking.

Our analysis spotlights elements like:

- Expressionist cinematography,

- Utilization of surrealism – Experimental editing techniques.

These visual innovators found resourceful ways to imbue their films with a sense of uniqueness.

The composition of scenes, the stark contrast in lighting, and the use of angular shots in The Mirror and the haunting ambiance of Stalker are prime examples.

This visual language spoke volumes, often conveying what dialogue could not.

Melding the unconventional styles with the weighted themes, Soviet Parallel Cinema remains an extraordinary case study in film history.

The directors and writers behind these movies left a lasting imprint on the psyche of the audience and future filmmakers.

Consider how the nuances in their approach to storytelling have influenced contemporary cinema, sparking a dialogue that transcends borders and generations.

Influential Filmmakers Of Soviet Parallel Cinema

Among the tapestry of Soviet Parallel Cinema, several directors stand out for their unparalleled contributions.

Aleksandr Sokurov and Kira Muratova are

Sokurov’s films, including Mother and Son and Russian Ark, are monumental in their visual and thematic depth.

His contemplative style bridges the personal and the historical, immersing audiences in intensely emotional experiences.

Muratova, on the other hand, brought a distinct perspective to Soviet Parallel Cinema.

Her films, such as The Long Farewell and Among Grey Stones, weave intricate narratives through an unconventional lens, challenging viewers to question the norm.

Her bold storytelling techniques mark her as a trailblazer within the movement.

- Key themes explored by these filmmakers include: – The endurance of the human spirit in the face of adversity – A critical eye on Soviet society and its shortcomings – An exploration of identity and personal freedom amidst a collectivist culture.

plus to Sokurov and Muratova, there were other influential directors who contributed significantly to the development of Soviet Parallel Cinema.

Tengiz Abuladze and his haunting Repentance boldly critiqued totalitarianism and provoked public discourse on Soviet history.

Each visionary director crafted a unique tapestry of images and narratives that not only defied censorship but also inspired audiences and filmmakers alike.

Their works remain a testament to the resilience of art in times of repression and continue to resonate with contemporary filmmakers searching for ways to push the boundaries of cinematic expression.

Legacy And Impact Of Soviet Parallel Cinema

The reverberations of Soviet Parallel Cinema are still felt in the film industry today.

By breaking away from the constraints of state-approved messaging and exploring new artistic territories, the movement has left a lasting imprint on contemporary cinema.

Not only did it challenge the aesthetic norms of its time, but it also introduced narrative styles and thematic concerns that remain influential across global film landscapes.

Directors inspired by pioneering figures like Aleksandr Sokurov, Kira Muratova, and Tengiz Abuladze carry forth a legacy of defiant storytelling and experimental technique.

Their films questioned the status quo and inspired a wave of independent filmmaking that continues to push creative boundaries.

Here are some key impacts of Soviet Parallel Cinema:

- Fostering Artistic Freedom: Filmmakers worldwide are now more emboldened to express dissenting perspectives and challenge political narratives.

- Revolutionizing Narrative Forms: The movement’s experimental storytelling has encouraged directors to break conventional narrative structures.

- Influencing Modern Cinematography: The distinctive visual styles pioneered during this era continue to inspire cinematographers and directors in their approach to visual storytelling.

The movement’s unconventional methods have also permeated film education, prompting a reevaluation of how cinema is taught and studied.

Discussions about form, content, and the role of the filmmaker have been greatly enriched by the contributions of Soviet Parallel Cinema.

As film theorists and historians, we continually uncover the ripples created by this movement and observe its profound influence on generations of filmmakers who seek to make their mark outside the mainstream.

What Is Soviet Parallel Cinema – Wrap Up

We’ve delved into the heart of Soviet Parallel Cinema, revealing its bold defiance against the grain of conventional filmmaking.

It’s a testament to the enduring spirit of artists like Sokurov, Muratova, and Abuladze, who dared to express the unspoken through their cinematic vision.

Their legacy lives on, challenging and inspiring filmmakers to explore beyond the surface and to tell stories that resonate with authenticity and courage.

As we reflect on the movement’s impact, we recognize its profound influence on the art of film and its ongoing role in shaping how we perceive and create cinema.

The echoes of Soviet Parallel Cinema continue to ripple through the industry, ensuring that its revolutionary spirit will never fade from our collective memory or from the silver screen.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Soviet Parallel Cinema?

Soviet Parallel Cinema was an artistic movement among filmmakers in the Soviet Union who sought to create films outside the norms of the state-controlled film industry.

They explored themes of human endurance, personal freedom, and societal criticism.

Who Were The Key Figures In Soviet Parallel Cinema?

Key figures in Soviet Parallel Cinema included Aleksandr Sokurov, Kira Muratova, and Tengiz Abuladze.

Their innovative work played a significant role in the movement’s development and its long-lasting impact on the film industry.

What Themes Did Soviet Parallel Cinema Explore?

The movement delved into a variety of themes, such as the perseverance of the human spirit, criticism of the oppressive aspects of Soviet society, identity, and the quest for personal freedom.

How Did Soviet Parallel Cinema Impact Modern Filmmaking?

Soviet Parallel Cinema broke away from state-approved messaging and introduced avant-garde narrative styles and thematic concerns, revolutionizing cinematography and influencing successive generations of filmmakers.

Did Soviet Parallel Cinema Face Censorship?

Yes, filmmakers associated with Soviet Parallel Cinema often defied censorship by the Soviet regime, as they strayed from the constraints and ideologies typically depicted in state-endorsed films.

How Has Soviet Parallel Cinema Influenced Film Education?

The unconventional methods and storytelling techniques of Soviet Parallel Cinema have permeated film education, leading to a reassessment of the ways cinema is taught and studied across the globe.

Essential Films Of Soviet Parallel Cinema

Here are some of the top films of Societ Parallel Cinema. These films highlight the diversity and depth of Soviet Parallel Cinema.

Each offers a unique perspective on life and society in the Soviet Union, using innovative cinematic techniques to tell stories that were often overlooked or suppressed in mainstream Soviet film.

Through their narratives, these films provide valuable insights into the complexities of Soviet life and the artistic rebellion that sought to challenge and redefine Soviet cinema.

The Mad Prince (1986)

The Mad Prince: The Mansion

Soviet Parallel Cinema

1986 • 1h 15min • ★ 8/10 • Soviet Union

Directed by: Boris Yukhananov

Cast: Masha-Larissa Borodina, Andrzej Zahariev von Brauch, Ada Bulgakov, Sergey Borisov, Boris Yukhananov

“Mansion” is the first part of the VHS series in which Yukhananov presented his experimental “Theater-Theater”.

This film is a fascinating exploration of the intersection between power and mental health. Set against a backdrop that subtly critiques Soviet authority, The Mad Prince uses its titular character to delve into themes of madness and control.

The narrative cleverly plays with the concept of what it means to be ‘mad’ in a society where conformity is often equated with sanity. The film’s direction and cinematography are remarkable, employing innovative techniques that were unconventional for the time.

The usage of symbolism and allegory in The Mad Prince makes it a thought-provoking watch, encouraging viewers to question the established norms of power and sanity

Sawyer (1984)

No poster available

Sawyer stands out as a poignant commentary on labor and individuality within the Soviet regime. The film’s narrative revolves around the life of a sawyer, whose mundane and repetitive job becomes a metaphor for the mechanization of human beings in a controlled society.

The director uses long, uninterrupted takes to emphasize the monotony of the work, allowing the audience to feel the protagonist’s growing sense of disillusionment.

The film subtly incorporates elements of existentialism, questioning the purpose of labor and the loss of individual identity in the face of overwhelming societal demands.

Metastases (1984)

Metastasis

1984 • 0h 16min • Soviet Union

Directed by: Igor Aleynikov

Found footage and found sound. Badly solarized training films, documentary fragments, speeches of USSR party leaders and rock 'n' roll form a horrifying picture of media pressure.

Metastases is a compelling portrayal of the transformative period in the Soviet Union during the early 1980s.

The film’s title itself suggests change and the spread of new ideas, mirroring the societal changes occurring at the time.

It blends elements of drama and documentary, creating a narrative that feels both personal and universally applicable to the Soviet experience.

The film focuses on how individuals and communities respond to these changes, grappling with the uncertainties of a society in flux.

The cinematography and use of color in Metastases are particularly notable, capturing the mood and tone of the era with a distinct visual style.

Short Film)” width=”500″ height=”375″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/z4Gvtb7g6Uo?feature=oembed” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” allowfullscreen>

Stand By Me (1986)

Stand by Me

For some, it's the last real taste of innocence, and the first real taste of life.

1986 • 1h 29min • ★ 7.9/10 • United States of America

Directed by: Rob Reiner

Cast: Wil Wheaton, River Phoenix, Corey Feldman, Jerry O'Connell, Kiefer Sutherland

After learning that a boy their age has been accidentally killed near their rural homes, four Oregon boys decide to go see the body. On the way, Gordie, Vern, Chris and Teddy encounter a mean junk man and a marsh full of leeches, as they also learn more about one another and their very different home lives. Just a lark at first, the boys' adventure evolves into a defining event in their lives.

Stand By Me offers a unique Soviet perspective on the themes of friendship, youth, and resilience.

The film is distinct from its American namesake, focusing on a group of young friends navigating the challenges of adolescence in the Soviet Union.

It portrays their journey of self-discovery against a backdrop of societal changes.

The director’s approach to storytelling is both intimate and expansive, capturing the small moments that define youth while also commenting on the larger societal shifts.

The film’s use of naturalistic dialogue and performances adds to its authenticity, making it a relatable and poignant exploration of growing up in a time of uncertainty.

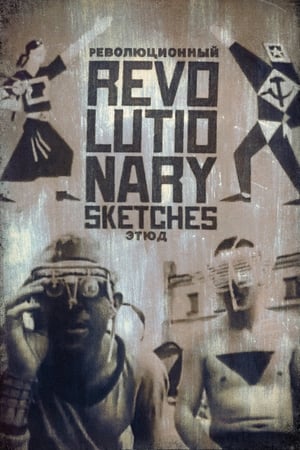

A Revolutionary Sketch (1987)

Revolutionary Sketches

1987 • 0h 8min

Directed by: Gleb Aleynikov

I know these were glasnost days, but still, I'm a little surprised filmmakers were out there doing stuff like this. There's nothing overtly anti-communist in this piece, but it ain't what you'd call respectful, 'neither. The brothers Aleinikov lay turgid governmental speeches about "the rearing of a new man" under footage of dudes goofing around in space-alien costumes, they roll footage of apple-cheeked future Stakhanovites upside down and backwards, they crudely animate -- in a certain South Parkian way -- CCCP icons in a goofy manner. Good, clean fun. (written by Colin Marshall)

This film is a critical examination of the Soviet revolution, offering a narrative that challenges the official histories and propaganda of the time.

A Revolutionary Sketch employs a mix of historical footage and fictionalized accounts to create a tapestry of events and perspectives surrounding the revolution. The film’s unconventional structure, blending documentary and narrative techniques, allows for a multifaceted exploration of its themes.

It raises questions about the nature of history, memory, and the construction of national narratives. The director’s use of contrasting imagery and editing techniques is particularly effective in highlighting the discrepancies between official stories and lived experiences.

I’m Cold, So What?/ I’m Frigid but it Doesn’t Matter (1987)

No poster available

This film stands out for its exploration of personal and emotional struggles within the context of a cold, indifferent society.

The title itself, I’m Cold, So What?/I’m Frigid but it Doesn’t Matter, reflects a sense of resignation and defiance in the face of societal apathy.

The narrative focuses on an individual’s search for warmth and connection in a world that seems increasingly alienating. The film’s style is characterized by its stark cinematography and minimalistic approach, creating a sense of isolation and introspection.

The use of symbolism and metaphor is particularly effective in conveying the protagonist’s inner turmoil and the coldness of the society they inhabit.

Short Film)” width=”500″ height=”375″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/1PCkTJNJ32Y?feature=oembed” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” allowfullscreen>

The Severe Illness of Men (1987)

No poster available

This film is a profound commentary on the psychological state of men in the late Soviet era. The Severe Illness of Men delves deep into the struggles of masculinity within a society that is both changing and stagnant. The film explores themes of identity, power, and vulnerability.

The director uses a combination of surreal imagery and realistic scenarios to create a narrative that is both unsettling and insightful.

The film’s visual style, characterized by stark contrasts and a moody color palette, effectively conveys the emotional turmoil of its characters.

The narrative structure, interspersed with symbolic elements, adds a layer of complexity to the film, inviting viewers to contemplate the societal expectations and personal realities of men during this period.

Supporter of Olf (1987)

Olf’s Supporter

1987 • 0h 5min • Soviet Union

Directed by: Evgeniy Debil

Cast: N. Mikhailovskaya, Konstantin Mitenev, Evgeniy Debil, Inal Savchenkov, Aleksandr Ovchinnikov

Expired film stock, DIY shooting and development often lead to mistakes. For instance, some of the material is good, but some is «sticky» when film sticks in the development tank leaving undeveloped an area up to 20 cm wide.

Supporter of Olf is a unique entry in the Soviet Parallel Cinema, focusing on themes of individualism and non-conformity.

The film’s narrative revolves around the character of Olf, a symbol of non-conformity in a conformist society. The film’s stylistic approach is marked by its use of surrealism and abstract storytelling. This approach creates a dreamlike atmosphere that blurs the line between reality and imagination.

The director’s use of unconventional camera angles and innovative editing techniques further enhances the film’s otherworldly feel. Supporter of Olf is notable for its critique of societal norms and its celebration of the individual’s quest for self-expression and freedom.

Spring (1987)

Manon of the Spring

They destroyed her father. Now they offered her love. But the only thing she desired was revenge.

1986 • 1h 53min • ★ 7.6/10 • France

Directed by: Claude Berri

Cast: Yves Montand, Daniel Auteuil, Emmanuelle Béart, Hippolyte Girardot, Margarita Lozano

In this, the sequel to Jean de Florette, Manon has grown into a beautiful young shepherdess living in the idyllic Provencal countryside. She plots vengeance on the men who greedily conspired to acquire her father's land years earlier.

Spring stands out for its metaphorical representation of rebirth and renewal. Set against the backdrop of the Soviet Union’s transformation, the film captures the essence of hope and change.

The narrative is structured around the metaphor of spring, symbolizing new beginnings and the end of a long, harsh winter. The director’s use of vibrant cinematography and natural landscapes captures the beauty and optimism of the season.

The film’s pacing and mood reflect the gradual, often tentative, awakening of society to new possibilities. Spring is a poetic and visually stunning film that offers a hopeful perspective on the future, amidst the uncertainties of a society in transition.

Boris and Gleb (1988)

No poster available

Boris and Gleb revisits historical figures from Russian history, offering a fresh and nuanced perspective.

This film stands out for its exploration of themes such as sacrifice, loyalty, and the complexities of power. By focusing on these two historical figures, the film delves into the moral and ethical dilemmas faced by individuals in positions of authority.

The director uses a blend of historical accuracy and artistic interpretation to create a narrative that is both engaging and thought-provoking.

The film’s cinematography, with its attention to period details and atmospheric settings, enhances the historical narrative, immersing the audience in the era.

Courage (1988)

No poster available

Mutter Courage und ihre Kinder

1988 • Germany

Directed by: Manfred Karge

Cast: Ursula Karusseit, Andreas Sindermann, Martin Brambach

Courage is a compelling exploration of the human spirit in the face of adversity. The film portrays the lives of ordinary people who display extraordinary bravery in challenging circumstances.

The narrative is marked by its emotional depth and character-driven storytelling. The director’s approach to the subject matter is both sensitive and powerful, capturing the nuances of courage in everyday life.

The use of close-ups and intimate camera angles creates a deep connection between the characters and the audience.

Courage is notable for its ability to evoke empathy and reflection on the part of the viewer, making it a significant contribution to the genre.

Boar Suicide (1988)

No poster available

Boar Suicide presents a unique and somewhat abstract narrative, known for its symbolic and metaphorical content.

The film’s title itself is intriguing and open to interpretation. It explores themes of destiny, choice, and the absurdity of existence.

The director employs a surrealistic style, blending reality with fantasy to create a narrative that challenges conventional storytelling.

The film’s visual style is striking, with a focus on contrasting imagery and unexpected visual motifs.

The use of allegory and symbolism in Boar Suicide makes it a thought-provoking piece, encouraging viewers to contemplate the deeper meanings behind the narrative.

Dreams (1988)

Bad Dreams

When Cynthia wakes up, she'll wish she were dead...

1988 • 1h 26min • ★ 5.7/10 • United States of America

Directed by: Andrew Fleming

Cast: Jennifer Rubin, Bruce Abbott, Richard Lynch, Dean Cameron, Harris Yulin

Unity Field, a "free love" cult from the '70s, is mostly remembered for its notorious mass suicide led by Harris, its charismatic leader. While all members are supposed to burn in a fire together, young Cynthia is spared by chance. Years later, the nightmare of Unity Field remains buried in her mind. But when those around Cynthia start killing themselves, and she begins having visions of Harris, she may be forced to confront the past -- before it confronts her.

A film that stands out for its exploration of the subconscious. It delves into the dreamscapes of its characters, revealing their deepest fears, desires, and fantasies.

The director uses a blend of surreal imagery and symbolic elements to create a narrative that is both ethereal and deeply rooted in the human psyche.

The film’s visual style is notable for its innovative use of color and lighting, creating a dream-like quality that blurs the lines between reality and imagination. Dreams invites the audience into a world of introspection, making it a profound and visually stunning cinematic experience.

Postpolitical Cinema (1988)

No poster available

Post-Political Cinema

1988

Directed by: Igor Aleynikov

Cast: Igor Aleynikov, Gleb Aleynikov

Postpolitical Cinema is a meta-commentary on the state of filmmaking within the Soviet context. This film questions the role of cinema in political discourse, challenging the conventions of traditional Soviet filmmaking.

The director uses a mix of documentary and narrative techniques, providing a critical examination of cinema as both an art form and a tool for political expression.

The film’s structure is unconventional, featuring a collage of different styles and perspectives, which serves to highlight the diversity and complexity of political and artistic expression in the Soviet era.

Someone Has Been Here (1989)

No poster available

Someone Has Been Here presents a poignant narrative about the transient nature of human existence.

The film explores the theme of impermanence through the lens of individuals whose lives intersect in unexpected ways.

The director’s use of storytelling focuses on the small, often overlooked moments that define our lives. The cinematography is marked by its attention to detail and a subtle, contemplative style, creating a sense of intimacy and realism.

This film is a reflection on the traces we leave behind and the fleeting connections that shape our experiences.

Awaiting de Bil (1990)

No poster available

Awaiting de Bil marks a transition into the post-Soviet era, capturing the anticipation and uncertainty of the time.

The film is set in a period of profound change and explores the societal and personal transformations that accompany such shifts.

The narrative is characterized by its depth and complexity, reflecting the myriad emotions and experiences of its characters.

The director employs a style that is both realistic and symbolic, using the backdrop of a changing society to explore themes of hope, fear, and the unknown future.

The Wooden Room (1995)

The Wooden Room

1995 • 1h 5min • ★ 4/10 • Russia

Directed by: Vladimir Maslov

Cast: Tatyana Verkhovskaya, Vladimir Maslov, Igor Bezrukov, Sergey Tsvetkov, Vasili Deryagin

The protagonist of The Wooden Room is a director of documentaries, who lives with his wife - who is as stoic as he - in an isolated hut in the woods. The director is obsessed by filming marginal events in life. The closer he can get to these events with his camera, the more he becomes involved with them. In the end he falls victim to them. The film, with no dialogue and hardly any sound, is an experimental meditation on the complex, continually-changing relationship between a film-maker and his subject.

The Wooden Room serves as a contemplative closure to the themes prevalent in Soviet Parallel Cinema. This film is a retrospective on the Soviet era, exploring the collective memory and the personal stories that define this period in history.

The narrative is marked by its introspective tone and a focus on the intimate aspects of life during the Soviet Union.

The film’s visual style is characterized by its simplicity and elegance, creating a sense of nostalgia and reflection.

The Wooden Room is a poignant and thoughtful exploration of history, memory, and the passage of time.

Ready to learn about some other Film Movements or Film History?