- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

Japanese New Wave cinema shattered conventions, introducing a style as bold and dynamic as the post-war era it sprang from.

We’ll explore how this movement rewrote the rules of filmmaking and narrative.

It’s a cinematic journey that brought us intimate stories, avant-garde techniques, and a new generation of filmmakers who weren’t afraid to challenge the status quo.

Join us as we jump into the heart of Japan’s most influential cinematic movement.

Japanese New Wave Cinema

What Is Japanese New Wave Cinema?

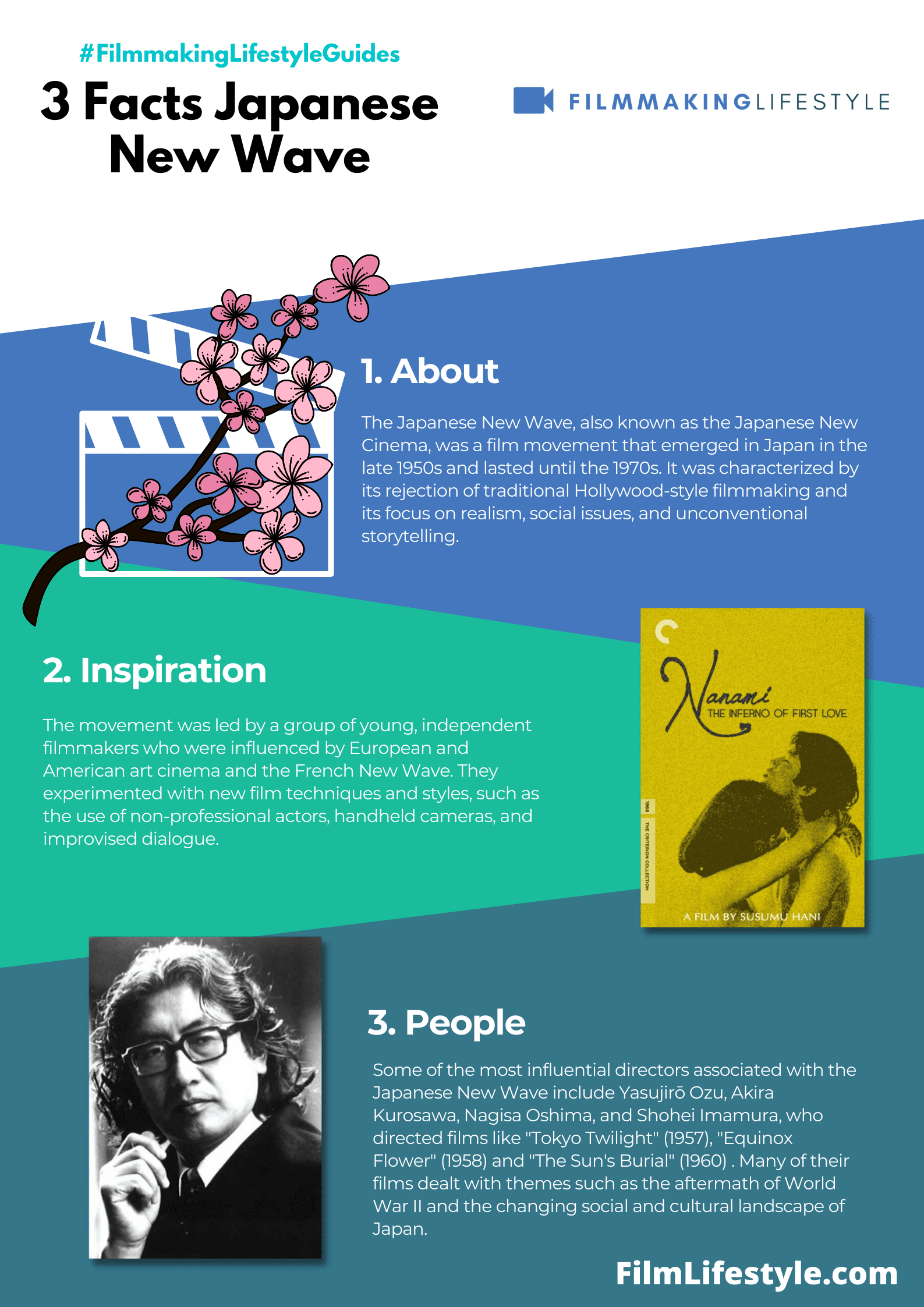

The Japanese New Wave, beginning in the late 1950s, was a movement that challenged the norms of the Japanese film industry.

It was marked by its embrace of avant-garde techniques, exploration of taboo subjects, and criticism of Japanese society and politics.

Filmmakers like Nagisa Oshima and Masahiro Shinoda were key figures, offering fresh and provocative perspectives through their films.

Origins Of Japanese New Wave Cinema

The Japanese New Wave, much like its French counterpart, had its genesis post-World War II.

Societal shifts and a hunger for artistic innovation spurred creators to transcend traditional storytelling.

Japanese cinema of the 1950s simmered with the energies of political dissatisfaction and cultural upheaval, creating an ideal breeding ground for a new cinematic language.

At the forefront was a cohort of young filmmakers, many emerging from the ranks of Shochiku and Nikkatsu studios.

These pioneers, initially assistant directors and scriptwriters, were keen on experimenting with form and content.

They sought to tell stories that resonated with the zeitgeist of contemporary Japan – tales of the marginalized, critiques of the establishment, and reflections on identity.

It was not merely the thematic elements that set the Japanese New Wave apart. Technical ingenuity paralleled narrative boldness – unexpected editing techniques, innovative sound design, and a daring visual aesthetic reshaped the viewer’s experience.

Films such as Sun’s Burial and Pigs and Battleships shattered convention with their raw depictions of societal fringes.

In the realm of independent cinema, the movement found additional momentum.

Maverick filmmakers took to the possibilities of 16mm and other economical production methods, chipping away at the glossy veneer of the studio system.

Perhaps it’s this very rejection of polished narratives and embrace of a gritty realism that lends the Japanese New Wave its enduring appeal in film circles today.

Cultural Context – The Post-war Era

After the devastation of World War II, Japan faced a period of reconstruction that had profound cultural implications.

During this time, filmmakers found themselves in a unique position – they were tasked with capturing the essence of a society in flux, while also navigating the limitations and censorship imposed by the Allied occupation.

The Japanese New Wave cinema was born out of this tumultuous landscape, serving as both mirror and critic of the changing norms.

With societal transformation as a backdrop, these films questioned traditional values and explored themes previously considered taboo.

Japan’s rapid economic growth and the generational tension between old and new ideals provided fertile ground for storytelling that was both revolutionary and reflective.

A sense of disillusionment and existential questioning permeated the era.

Young people, in particular, sought to establish their own identity separate from the national narrative of recovery and growth.

This shift lent itself to narratives that focused on individualism and the breakdown of familial structures – a stark contrast to the collectivist ethos that had dominated Japanese culture.

In response, the Japanese New Wave employed novel approaches to film form and aesthetics that aligned with their thematic concerns:

- A departure from classical storytelling techniques,

- Innovative use of the camera to express psychological states,

- An embrace of modernist techniques, often influenced by European cinema.

As part of our ongoing exploration of film movements, we’re delving into how these approaches not only redefined Japanese cinema but also how they mirrored broader societal changes.

Directors like Nagisa Oshima and Masahiro Shinoda pushed the boundaries of narrative structure whereas films like Cruel Story of Youth and The Sun’s Burial offered unflinching social critiques.

In essence, the Japanese New Wave was much more than a cinematic style; it was a dialogue with a nation’s soul, attempting to grapple with its past while carving out a path toward an uncertain future.

Through our lenses, we’re witnessing an unmatched legacy that continues to inspire filmmakers globally.

Characteristics Of Japanese New Wave Cinema

One of the defining traits of the Japanese New Wave was its rebellious spirit.

This cinema movement differentiated itself from mainstream productions by challenging the status quo and confronting social issues head on.

Directors within this movement often explored topics like political unrest, sexual liberation, and existential questioning through their groundbreaking work.

At the heart of these films were often complex characters and narratives that reflected the disaffection of Japan’s youth.

Think of the brooding anti-heroes and the disillusioned young individuals in Pale Flower and Pigs and Battleships.

These characters and their personal struggles became a lens through which audiences could view the larger societal upheavals of post-war Japan.

Another hallmark of the Japanese New Wave was innovative cinematography and editing.

Filmmakers utilized techniques such as:

- Hand-held camera work – offering a raw, intimate feel,

- Jump cuts and unconventional narrative structures – disrupting the flow of the story to engage viewers in new ways,

- Unorthodox use of sound and visual juxtaposition – to create a distinct atmosphere and emotional impact.

Independent production companies were instrumental in fostering the Japanese New Wave.

With less stringent oversight compared to major studios, these companies provided a platform for filmmakers to experiment with content and style.

Films like Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter exemplified the creative freedom enjoyed by directors who ventured off the beaten path.

Our appreciation of the Japanese New Wave also entails acknowledging the international influences that shaped it.

The movement’s pioneers were inspired by the works of European filmmakers and they infused those elements with traditional Japanese storytelling.

This intersection of East and West contributed to the unique aesthetic and thematic qualities we recognize today in Japanese New Wave cinema.

Influential Filmmakers Of The Movement

As experts in film movements across the globe, it’s

Among these, Nagisa Oshima stands tall – a director whose unorthodox approaches to narrative and aesthetic broke away from the trends of the era.

Night and Fog in Japan and In the Realm of the Senses remain landmarks, showcasing Oshima’s bold commentary on politics and sexuality.

Another architect of the movement, Seijun Suzuki, is revered for his avant-garde style and flair for yakuza films that defied genre conventions.

Branded to Kill is iconic, not just within the Japanese New Wave but in global cinema, for its striking visuals and narrative experimentation.

Suzuki’s work influenced future generations of filmmakers, encouraging creative freedom and innovation.

Here are a few other trailblazers who shaped the cinematic landscape:

- Shohei Imamura who delved into the lives of the working class and societal outcasts with films like The Insect Woman,

- Masahiro Shinoda’s Pale Flower, introducing a more introspective style within the crime genre,

- Hiroshi Teshigahara – his film Woman in the Dunes blended existential philosophy with a stark surrealism.

These directors didn’t just push narrative boundaries; they also expanded the visual and auditory language of cinema.

Hand-held cameras, natural lighting, and ambient sound were among the techniques that moved Japanese film away from its studio-bound roots.

Their collective works succeeded in challenging audiences worldwide, prompting viewers to question not only the subjects on screen but also the very nature of film.

Impact And Legacy Of Japanese New Wave Cinema

The ripple effects of the Japanese New Wave have been felt across the globe for decades, with its influence permeating various film cultures and movements.

Filmmakers worldwide drew inspiration from the movement’s ability to tell stories that were visually arresting and narratively complex.

The boldness of the New Wave’s thematic content paved the way for similarly daring work in cinemas from Latin America to Europe.

One can trace a direct line from the Japanese New Wave to contemporary cinema, particularly in art house and independent films.

Its fingerprints are present in the non-linear storytelling, the nuanced and complex characters, and the innovative use of camera and sound that have become hallmarks of modern filmmaking.

Adept at creating atmospheres and jolting viewers out of passivity, these films continue to challenge and inspire today’s directors.

- Our influence as filmmakers extends beyond the camera lens – we tell stories that resonate and propel narrative techniques forward,

- Influential directors from the New Wave era set a precedent for experimentation and breaking norms that has encouraged subsequent generations to push the boundaries of what’s possible in film.

The legacy of the Japanese New Wave is not confined to stylistic and narrative innovation; it ignited a critical discussion on societal norms.

Films from this period remain stark reflections of the issues they tackle, standing as historical documents that offer insight into Japan’s post-war climate.

The social commentary embedded within these films ensures their relevance and keeps them at the forefront of film studies.

Independent cinema owes a significant debt to the Japanese New Wave, highlighting the movement’s ability to democratize the process of filmmaking.

Lower-budget productions demonstrated that impactful stories could be told without the backing of major studios, encouraging filmmakers to explore personal and provocative subjects.

This ethos has underpinned independent film sectors worldwide, showcasing the power of artistic voice over commercial appeal.

What Is Japanese New Wave Cinema – Wrap Up

We’ve seen how the Japanese New Wave revolutionized cinema, infusing it with a fresh perspective that resonated globally.

Our exploration has unveiled a movement that not only redefined film form and aesthetics but also held a mirror to society, challenging norms and sparking dialogue.

The legacy of these films is undeniable, as they continue to inspire filmmakers and captivate audiences with their groundbreaking approaches to storytelling and their poignant social critiques.

Let’s not forget the courage of those independent filmmakers whose innovative spirit paved the way for the vibrant and diverse cinema culture we enjoy today.

Their contributions to the art of filmmaking have ensured that the Japanese New Wave remains a touchstone for cinematic excellence and a beacon for creative expression.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is The Japanese New Wave Cinema?

The Japanese New Wave is a cinematic movement that emerged after World War II, characterized by its experimental approach to storytelling, embracing thematic boldness, and technical innovation reflecting Japan’s changing society.

When Did The Japanese New Wave Begin?

The movement began in the post-WWII era, with young filmmakers starting to experiment with new cinematic forms and content in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s.

Who Were The Major Studios Involved In The Japanese New Wave?

Studios like Shochiku and Nikkatsu were at the forefront of the Japanese New Wave, providing platforms for filmmakers to explore innovative film techniques and unconventional narratives.

What Themes Did The Japanese New Wave Address?

The movement addressed societal changes in post-war Japan, questioning traditional values and exploring taboo subjects such as individualism, generational tension, and the breakdown of familial structures.

How Did The Japanese New Wave Differ From Classical Filmmaking?

It differed in adopting modernist techniques influenced by European cinema, using novel approaches to film form, including hand-held camera work, jump cuts, and non-linear storytelling.

Which Directors Were Influential In The Japanese New Wave?

Directors like Nagisa Oshima, Seijun Suzuki, Shohei Imamura, Masahiro Shinoda, and Hiroshi Teshigahara were pivotal, known for pushing narrative and aesthetic boundaries in their films.

What Impact Did The Japanese New Wave Have On Global Cinema?

The movement influenced filmmakers worldwide with its narrative complexity and visual inventiveness, paving the way for future bold thematic content and inspiring various cinema movements and art house films.

How Do Modern Films Reflect The Influence Of The Japanese New Wave?

Contemporary cinema often showcases non-linear storytelling, complex characters, and innovative techniques such as natural lighting and ambient sound, tracing back to the New Wave’s legacy.

What Role Did Independent Production Companies Play In The Movement?

Independent companies were crucial in fostering the New Wave, allowing filmmakers the freedom to experiment and produce innovative content without major studio constraints.

Why Are Films From The Japanese New Wave Still Relevant Today?

These films are historical documents providing insights into Japan’s post-war climate, with their embedded social commentary ensuring ongoing relevance and importance in film studies.

They also laid the groundwork for independent cinema’s focus on artistic voice over commercial appeal.

Ready to learn about some other Film Movements or Film History?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

2 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

It would be nice if you had sources and date published

Working on it, Mark. We have a very small content team. These posts are dynamic and a work in progress. Always updating.

Thanks for your interest.