- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

Direct cinema is a documentary genre that lets reality speak for itself.

It’s a style that strips away the influence of a director’s touch, aiming to present the subject matter as truthfully as possible.

We’ll dive into the roots of this filmmaking technique and explore its impact on the way we perceive truth in film.

Stay with us as we uncover the nuances of direct cinema, a method that challenges filmmakers to become flies on the wall, capturing life’s raw, unfiltered moments.

What Is Direct Cinema

What Is Direct Cinema?

Direct Cinema is a documentary film style that emerged in North America in the late 1950s and 1960s. It aims to present a straightforward, unobtrusive depiction of real events, people, and situations, with minimal intervention from the filmmaker.

The style is characterized by long takes, handheld camera work, and the absence of narration or directorial commentary. This approach seeks to capture the truth or reality of a situation as it unfolds, giving viewers an immersive and authentic experience.

Pioneers of this style include filmmakers like D. A. Pennebaker, Albert and David Maysles, and Frederick Wiseman. Direct Cinema played a crucial role in the evolution of documentary filmmaking, influencing numerous filmmakers and styles that followed.

Origins Of Direct Cinema

The seeds of direct cinema were planted in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

During this era, a quest for a new form of documentary storytelling began, diving into the lives of its subjects with an unflinching eye.

Filmmakers sought to simplify the filmmaking process, stripping away the artifice to reveal a deeper truth.

It was in this fertile ground that direct cinema took root, drawing inspiration from the earlier movement of cinéma vérité.

However, direct cinema distinguishes itself with a stricter adherence to the observational role of the filmmaker.

Our cameras serve as silent witnesses, eschewing narration and the director’s interpretive influence.

A pivotal moment for direct cinema was the introduction of portable film equipment.

As technology evolved, lightweight cameras and sync sound recorders enabled us to capture life as it unfolded, spontaneously and authentically.

Classics like Primary and Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment demonstrated just how powerful this immediacy could be, inviting audiences to watch pivotal moments play out in real-time.

Direct cinema’s unobtrusive approach also signaled a shift in the dynamic between the subject and the camera.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Direct Cinema film movement, check out our in-depth profile and explore our comprehensive timeline of film movements to see where it fits in cinema history.

With the presence of the camera becoming less obtrusive, people behaved more naturally.

This allowed for a purity of expression that traditional documentary methods often diluted.

These innovations sparked a revolution in nonfiction storytelling.

We started to explore stories not just as narrators but as discreet observers, opening the door to a myriad of truths and perspectives previously unseen in film.

As a result, direct cinema challenged us to reconsider the role of the filmmaker and the very nature of reality as presented through the lens.

Principles Of Direct Cinema

As we delve into the core principles of direct cinema, it’s crucial to recognize the elements that set this filmmaking genre apart.

Transparency in the filmmaking process is key.

Filmmakers adopt a fly-on-the-wall approach, which means the camera’s presence is minimized to avoid influencing the scene.

The subjects often forget about the presence of the camera, allowing for an uninhibited and genuine portrayal of events.

The second principle is immediacy.

Direct cinema aims to capture events as they occur, emphasizing spontaneity and the significance of the present moment.

The technique hinges on filmmakers being present where and when events unfold, often operating with a level of agility unheard of in more traditional film settings.

This approach can be seen in works like Primary, which provided an unfiltered look into the 1960 Wisconsin Democratic Primary.

Lastly, direct cinema is defined by non-intervention.

The role of filmmakers is to observe without interaction or interference in the narrative.

This non-interventionist stance is what separates direct cinema from cinéma vérité, which occasionally involves the director’s influence.

By maintaining objectivity and refraining from manipulation, the authenticity of the footage is preserved, offering audiences an unadulterated slice of reality.

Notable Direct Cinema Filmmakers

Exploring direct cinema further, it’s impossible not to highlight the individuals who’ve shaped this genre into what it is today.

Pioneering figures like Richard Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, and Albert Maysles, stand as titans in the field.

These filmmakers set the stage, creating some of the most influential works that define the essence of direct cinema.

Their contributions can be seen in films like Primary and Chronicle of a Summer, where Leacock and Pennebaker, respectively, employed their observational methods to craft narratives that serve as cornerstones in documentary storytelling.

The Maysles brothers’ Grey Gardens is another exemplar of the genre, offering a raw and intimate look into its subjects’ lives.

Building on the legacy of these early visionaries, contemporary filmmakers continue to push the boundaries of direct cinema.

Laura Poitras, with Citizenfour, and Matthew Heineman, through Cartel Land, utilize immersive techniques to bring urgent stories to the foreground.

These directors carry the torch, ensuring that the tenets of direct cinema remain alive in modern documentary filmmaking.

Each filmmaker brings their unique voice to the genre, yet all share a common commitment to the direct cinema principles of transparency and organic storytelling.

The result is a body of work that not only tells a story but also connects viewers directly with the pulse of the moments captured.

Through their eyes, we observe scenes seemingly untouched by the filmmakers’ presence, offering viewers an authentic experience.

The influence of their work resonates across cinema and continues to inspire countless filmmakers in the art of true-to-life storytelling.

Top Direct Cinema Films

Here are a couple of the top direct cinema gems.

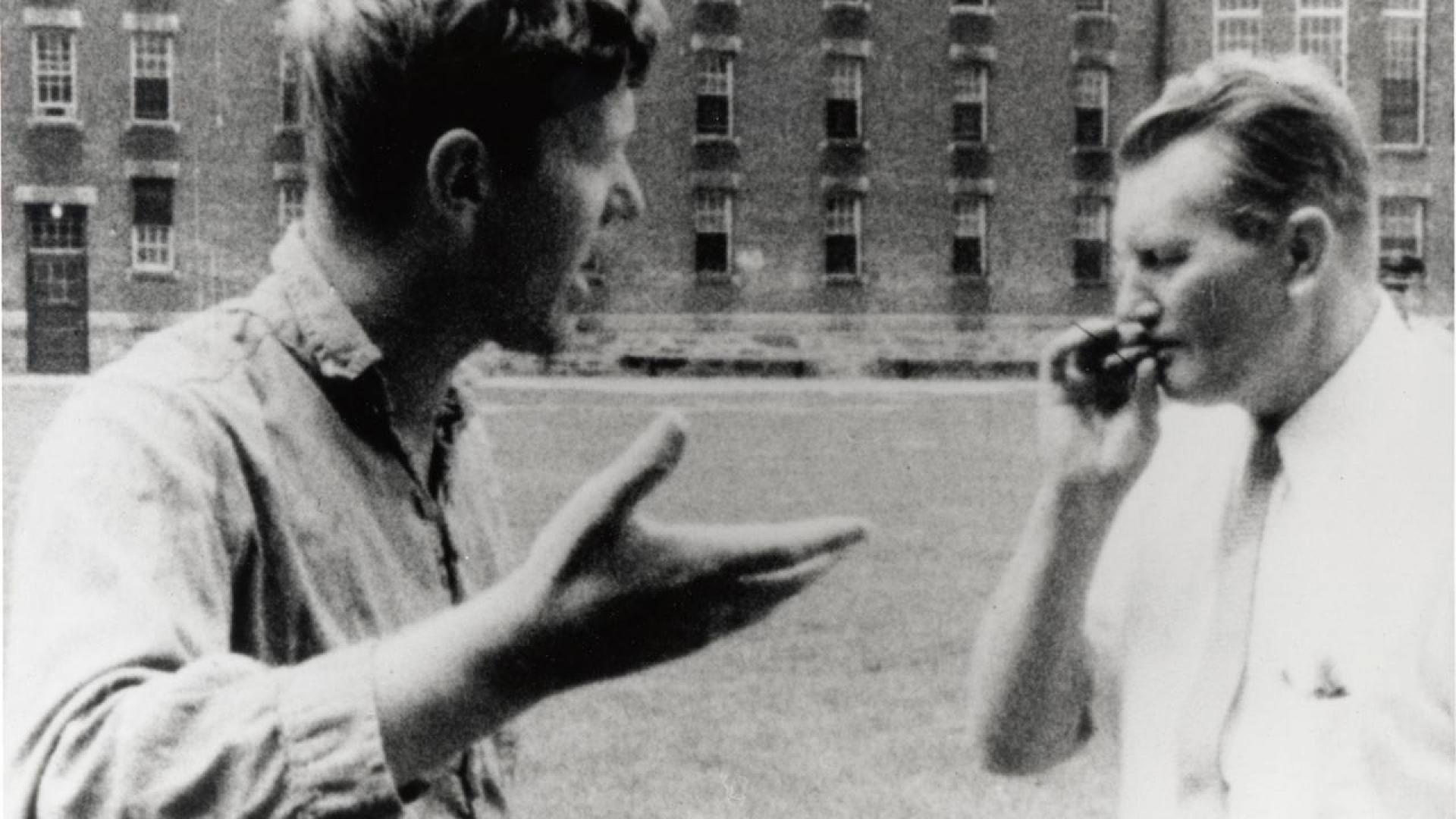

Titicut Follies (1967)

Titicut Follies

Don't turn your back on this film if you value your mind or your life.

1967 • 1h 24min • ★ 7.24/10 • United States of America

Directed by: Frederick Wiseman

A stark and graphic portrayal of the conditions that existed at the State Prison for the Criminally Insane at Bridgewater, Massachusetts, and documents the various ways the inmates are treated by the guards, social workers, and psychiatrists.

This documentary is told from the point of view of inmates at a Massachusetts state prison for the criminally insane. This documentary sparked a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case (Estelle v. Gamble) and helped launch the prison reform movement of the 1970s.

Field Goal (1977)

No poster available

This film was shot at Iowa’s Camp Dodge, where more than 25,000 WWII veterans returned to train as part of their rehabilitation. Field Goal explores what happens when loneliness and war memories are left untreated.

Evolution And Impact Of Direct Cinema

Direct cinema has undergone significant transformation since its inception, its impact resonating through both the film industry and beyond.

Initially rooted in the desire to portray reality without manipulation, this genre has evolved, with technology playing a pivotal role.

Portable sync-sound equipment, for instance, allowed filmmakers to capture life as it unfolded, a stark contrast to the controlled environment of traditional filmmaking.

Throughout the years, direct cinema has influenced not just documentaries, but also narrative filmmaking and television.

Shows like The Office and films such as The Blair Witch Project owe a debt to the observational techniques pioneered by direct cinema.

These productions mimic the genre’s authentic style, blurring the lines between reality and fiction and creating immersive experiences for audiences.

The legacy of direct cinema also extends to how we perceive truth in media.

Filmmakers adopting this style often tackle pressing social issues, provoking critical thought and fostering public discourse.

These films not only entertain but also serve as catalysts for change, shedding light on topics that might otherwise remain hidden.

Digital and mobile technologies have democratized filmmaking, allowing anyone with a smartphone to adopt a direct cinema approach.

As barriers to entry continue to fall, we’re witnessing a surge in user-generated content that embodies the spontaneous and unfiltered essence of the genre.

Social media platforms have become hubs for this new wave of direct filmmakers, reshaping the way we share and consume stories.

Finally, the internet has significantly increased accessibility to films, offering a global platform for direct cinema.

Online streaming services and video-on-demand platforms present these works to diverse audiences, facilitating cross-cultural dialogues and expanding the reach of films that might have previously been constrained by geographical limitations.

This interconnectedness enables filmmakers to achieve a level of impact that was once unimaginable, ensuring that the essence of direct cinema continues to thrive and influence.

Challenges And Criticisms Of Direct Cinema

While direct cinema has made an indelible mark on the film industry, it’s not without its challenges and criticisms.

One of the main issues it faces is the question of objectivity.

Despite attempts at pure observation, filmmakers’ choices in what to shoot and what to edit often reflect a certain bias, raising questions about the authenticity of the narrative being presented.

The ethical implications of capturing real people on film have also sparked debates.

Subjects in direct cinema projects may not fully grasp the impact of their involvement or how the footage will be used, leading to concerns over consent and the potential exploitation of those on camera.

Furthermore, technological limitations initially set boundaries on the kind of stories that could be told.

Early equipment was bulky and obtrusive, which sometimes altered the behavior of those being filmed and limited the filmmakers’ ability to remain unobtrusive observers.

In response to these challenges, critics of direct cinema argue that the genre fails to deliver the unfiltered reality it promises.

They contend that all documentaries, including those in the style of direct cinema, are ultimately shaped by the filmmaker’s point of view and are, therefore, crafted narratives rather than unmediated truths.

Finally, in our ever-evolving digital age, the distinction between direct cinema and other forms of documentation has become increasingly blurred.

User-generated content often shares characteristics with direct cinema but lacks the deliberate artistic intention and curation typically associated with the genre.

This proliferation of content has led to further examination of what distinguishes professional direct cinema work from the broader landscape of reality-based media.

What Is Direct Cinema – Wrap Up

We’ve journeyed through the compelling world of direct cinema, uncovering its profound influence on the landscape of film and television.

It’s clear that this genre has reshaped our understanding of storytelling, inviting us to experience a more authentic connection with the subject matter.

As technology continues to evolve, so too will the methods and impact of direct cinema.

Despite the debates surrounding its objectivity and ethics, there’s no denying that this style of filmmaking has left an indelible mark on the way we view reality through the lens of a camera.

Looking ahead, we’re excited to see how new generations of filmmakers will harness the principles of direct cinema to tell their truths and challenge our perceptions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Direct Cinema?

Direct cinema is a genre of documentary filmmaking that strives to capture the reality of a situation through unobtrusive observation.

It avoids narration, interviews, and artificial setups, aiming to offer a more authentic and immersive viewing experience.

Who Are Some Notable Filmmakers In Direct Cinema?

Filmmakers like Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, and the Maysles brothers are among the pioneers of the direct cinema genre.

Their work has significantly influenced documentary filmmaking and set the standards for the genre.

How Has Technology Impacted Direct Cinema?

Technological advancements have greatly influenced direct cinema by making equipment more accessible and portable, allowing for intimate and spontaneous recording of events.

Digital and mobile technologies facilitate user-generated content that reflects the principles of direct cinema.

Can Direct Cinema Influence Narrative Filmmaking And Television?

Yes, direct cinema has influenced both narrative filmmaking and television.

TV shows like “The Office” and films such as “The Blair Witch Project” incorporate its observational techniques to create a sense of realism and immediacy.

Does Direct Cinema Accurately Convey The Truth?

While direct cinema aims to truthfully depict reality, there are criticisms regarding its objectivity.

All documentaries, including those in the style of direct cinema, are influenced by the filmmaker’s perspective and choices, challenging the

What Challenges Does Direct Cinema Face Today?

Direct cinema faces challenges such as maintaining objectivity, navigating ethical considerations, and dealing with technological limitations.

Furthermore, the distinction between direct cinema and other forms of documentation is blurred due to the proliferation of user-generated content.

Matt Crawford

Related posts

2 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Great site. Education gives us an understanding of the world around us and offers us an opportunity to use that to success.

Absolutely! Thanks, Carol.