- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

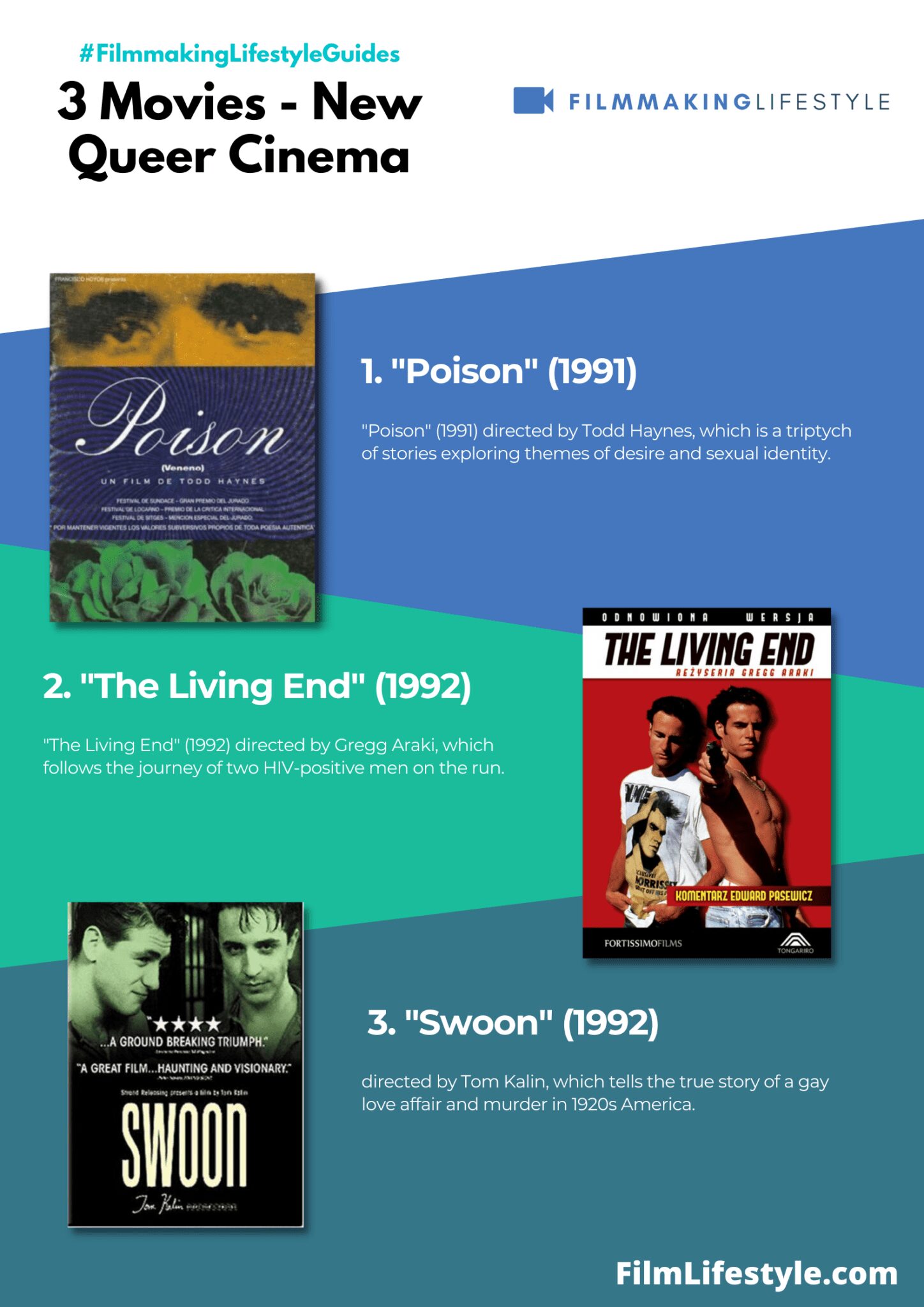

New Queer Cinema burst onto the scene as a provocative and vibrant movement in early ’90s filmmaking.

It’s a form of expression that challenges traditional narratives and gives voice to LGBTQ+ stories with unapologetic honesty and flair.

In this article, we’ll jump into the origins, key features, and groundbreaking impact of New Queer Cinema.

We’re set to explore how this movement reshaped the landscape of queer representation in film, so buckle up for an enlightening ride through cinema’s boldest frontier.

New Queer Cinema

What Is New Queer Cinema?

New Queer Cinema emerged in the early 1990s, a term coined by film critic B. Ruby Rich, to describe a movement in filmmaking that focused on LGBTQ+ narratives.

This movement represented a significant shift from the traditional portrayal of queer characters and stories in cinema.

Films in this category often challenge stereotypes and conventional narratives, offering more complex and varied representations of queer experiences.

Directors like Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, and Gregg Araki were prominent in this movement, bringing an innovative and bold approach to queer storytelling.

Origins Of New Queer Cinema

The roots of New Queer Cinema can be traced back to the late 1980s and early 1990s, a period of significant social and political upheaval.

This was a time marked by the height of the AIDS crisis and the corresponding activism that it spurred.

As artists and filmmakers within the LGBTQ+ community sought to reflect their experiences authentically, they turned to cinema as a powerful medium for expression and resistance.

Films like Paris is Burning and Tongues Untied serve as seminal works that capture the ethos of the movement – they broke away from heteronormative storytelling and aesthetics, setting the stage for what would evolve into New Queer Cinema.

These films, among others, laid the groundwork by showcasing LGBTQ+ lives and stories with a directness and rawness that had been previously unseen in mainstream media.

Our understanding of the movement wouldn’t be complete without considering the role of film festivals and indie theaters.

They played a crucial part in the proliferation of New Queer Cinema:

- Sundance Film Festival showcased many pioneering works,

- Outfest and Frameline helped these films reach a broader audience – Smaller, independent theaters created safe spaces for LGBTQ+ narratives to flourish.

The confluence of these factors – the social context, the bold creativity of early queer films, and the burgeoning indie cinema scene – provided the perfect breeding ground for New Queer Cinema to emerge.

This movement continued to pick up momentum, bolstered by critical acclaim and the backing of a community hungry for representation.

It’s within this vibrant atmosphere that New Queer Cinema found its voice and began to influence both indie and mainstream filmmaking.

Key Features Of New Queer Cinema

New Queer Cinema is marked by several distinctive features that set it apart from traditional film narratives.

One characteristic is the emphasis on character subjectivity and personal experience, often through a narrative lens that challenges the dominant heteronormative discourse.

These stories are crafted with authenticity and a raw, unfiltered perspective into the lives and struggles of LGBTQ+ individuals.

Another hallmark is the aesthetic innovation typical of this movement.

Filmmakers Use experimental techniques, non-linear storytelling, and a blend of genres to convey the complex and diverse narratives of the LGBTQ+ community.

Films such as My Own Private Idaho and The Living End exemplify this departure from conventional filmmaking practices and showcase the inventive visual style of New Queer Cinema.

Not only narrative and aesthetics, but New Queer Cinema also represents a shift in political engagement:

- Addressing topics such as AIDS, homophobia, and transgender issues head-on.

- Aligning with the broader activist movements of the time, with filmmakers not shying away from provocative and challenging content.

finally, there’s the vibrant queer sensibility that permeates these films.

This is not just an acknowledgment of LGBTQ+ culture but an embrace and celebration of it.

New Queer Cinema moves beyond mere representation to create a space where queer identities can exist without conforming to mainstream expectations, as seen in The Watermelon Woman and Hedwig and the Angry Inch.

Through these core features, New Queer Cinema has established a legacy of challenging the status quo and giving a platform to voices that, for too long, were sidelined in cinematic storytelling.

It’s a movement that redefined what a film could be and who it could represent, changing the landscape of cinema in the process.

Impact Of New Queer Cinema

The influence of New Queer Cinema has been profound within both the indie circuit and mainstream media.

Pioneering works like My Own Private Idaho and The Living End inspired a generation of filmmakers and audiences.

We’ve observed an increase in films that challenge traditional gender roles and sexual identities, encouraging a more nuanced understanding of the LGBTQ+ community.

New Queer Cinema not only reshaped LGBTQ+ representation on screen but also fueled debates on social issues and civil rights.

Movies that exemplify the essence of the movement foster discussions around topics such as:

- Same-sex relationships and marriage equality,

- Gender identity and transgender rights,

- The impact of HIV/AIDS on the gay community.

Increased visibility has been crucial in fostering societal acceptance and understanding.

Films like Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Boys Don’t Cry offered raw, unapologetic portraits of queer lives, sometimes with the consequence of controversy but always with a push towards progress.

Our analysis of the cultural impact reveals that New Queer Cinema played a significant role in propelling queer theory and studies into academic circles.

It’s not only about the narratives; the movement’s aesthetic and thematic innovations have become subjects of scholarly research and discussion across the globe.

Through academic discourse, these films continue to enrich conversations around queer identities and politics.

finally, New Queer Cinema has been instrumental in heralding a wave of creators who’ve diversified the industry.

By breaking barriers, these films and their makers have opened doors for queer and marginalized filmmakers, prompting a more inclusive and representative filmmaking landscape.

The movement’s legacy lives on as it continuously inspires new work that reflects the ever-evolving dimensions of queer experiences.

Reshaping Queer Representation In Film

New Queer Cinema rebelled against the tropes and stereotypes that previously shackled queer characters in film.

It carved out a space for complex, multifaceted representations, where protagonists could embody a range of desires and identities.

The movement allowed filmmakers to explore topics of sexuality and gender with unprecedented depth, often drawing from their personal experiences to infuse their work with authenticity.

With films like My Own Private Idaho and The Living End, the New Queer Cinema movement expanded the horizons of LGBTQ+ narratives.

These weren’t just stories about coming out or facing external bigotry; they delved into the intricacies of queer relationships, the nuances of sexual identity, and the internal conflicts that accompany life as part of a marginalized community.

Films that emerged from this movement were marked by several distinctive features:

- Aesthetic innovation – filmmakers utilized unconventional cinematic techniques to mirror the non-conformity of their characters,

- Political engagement – many works offered a critique of societal norms and portrayed the struggle for acceptance and equality,

- Rich character subjectivity – there was a shift to focus on the internal life of queer characters, rather than just their exterior experiences.

The legacy of New Queer Cinema persists as filmmakers continue to push boundaries.

They challenge audiences to question their perspectives and offer a more inclusive view of the world.

This movement did more than just tell new stories; it transformed the entire landscape of what queer storytelling could be in the realm of film.

One of the primary triumphs of New Queer Cinema was its dismantling of the heteronormative gaze within mainstream media.

This shift gave rise to an era where films could portray queer love, angst, and joy without filtering it through a straight lens.

It invited viewers of all backgrounds to see parts of themselves reflected on screen, perhaps for the first time.

What Is New Queer Cinema – Wrap Up

New Queer Cinema reshaped our cultural landscape, ensuring that queer stories are told with the authenticity and complexity they deserve.

We’ve seen how this movement broke away from restrictive norms, forging a path for filmmakers to explore the rich tapestry of LGBTQ+ life.

Its influence is undeniable, continuing to ripple through the film industry and beyond.

We’re inspired by the courage and creativity of these storytellers, and we’re excited to witness the ongoing evolution of queer narratives in cinema.

Let’s celebrate the diversity and depth that New Queer Cinema has brought to the screen, and look forward to the stories yet to be told.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is New Queer Cinema?

New Queer Cinema refers to a filmmaking movement that arose in the late 1980s and early 1990s, characterized by its representation of queer characters with complexity and authenticity, challenging previous stereotypes.

When Did New Queer Cinema Begin?

The New Queer Cinema movement began in the late 1980s and gained prominence in the early 1990s.

What Are The Key Characteristics Of New Queer Cinema?

Key characteristics of New Queer Cinema include aesthetic innovation, political activism, and a focus on the rich inner lives and subjectivities of LGBTQ+ characters.

How Did New Queer Cinema Change The Portrayal Of Lgbtq+ Individuals In Film?

New Queer Cinema dismantled the heteronormative gaze in mainstream media, allowing for queer love and experiences to be portrayed without being filtered through a straight viewpoint.

What Is The Legacy Of New Queer Cinema?

The legacy of New Queer Cinema lives on as it continues to inspire modern filmmakers to push narrative and aesthetic boundaries and offer more inclusive worldviews in their work.