- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

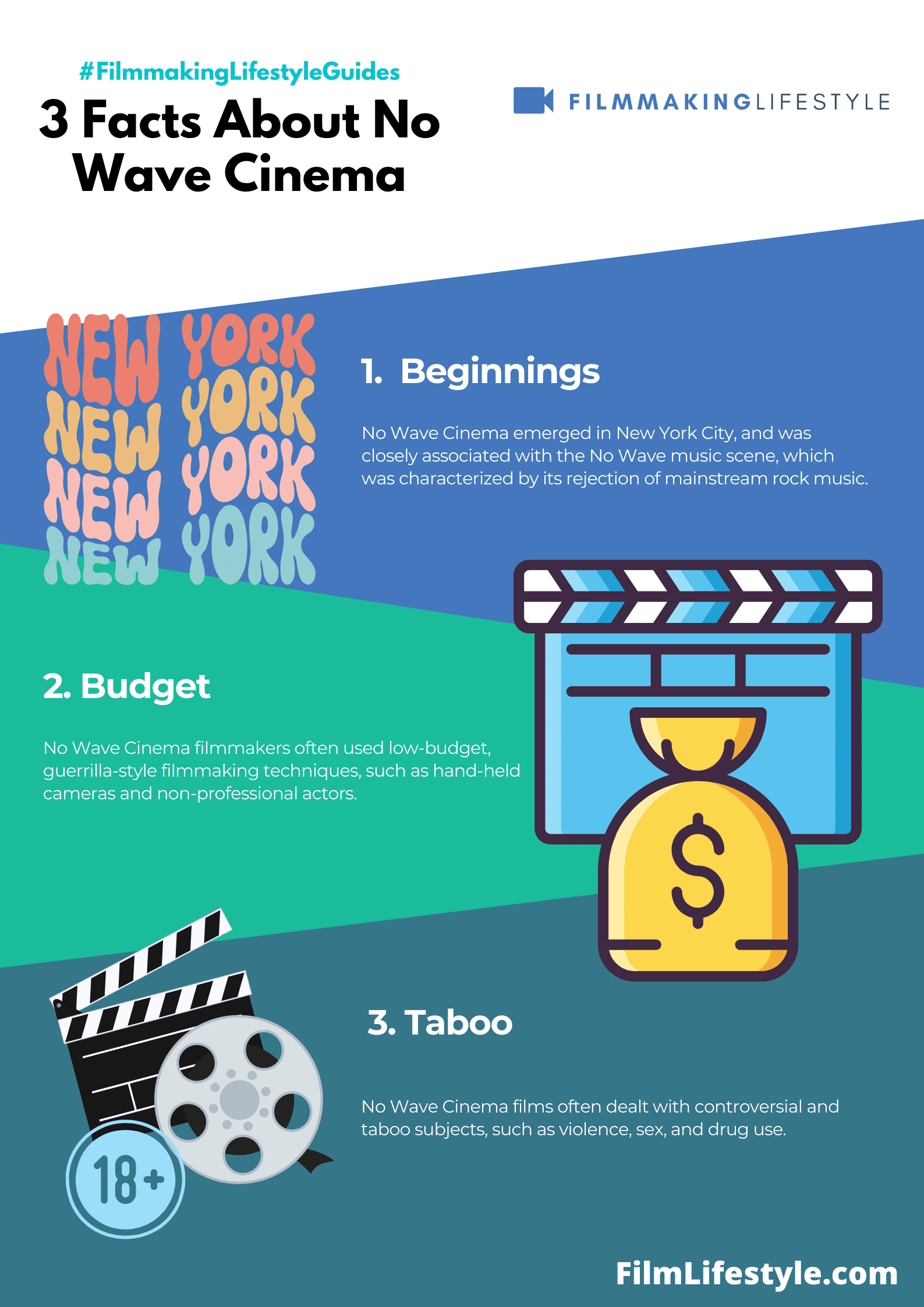

No Wave Cinema is a radical underground film movement that emerged in the late 1970s in New York City.

It’s known for its gritty, low-budget aesthetic and its rejection of conventional storytelling.

We’ll jump into the origins of No Wave Cinema, explore its key figures, and discuss why it’s still influential in today’s indie film scene.

If the French New Wave was a movement that aimed to shock and provoke, then No Wave cinema was the next logical step.

The late ’70s and early ’80s found New York City in economic decline, with crime rates soaring and many residents fleeing the boroughs for more peaceful pastures.

It was during this period of troubled transition that several brilliant young filmmakers decided to embrace their surroundings as material and create an entirely new genre of cinema.

Often referred to as No Wave cinema, this movement would take on a variety of names including New Cinema, underground film, avant-garde cinema, etc., but it would always retain its essential nihilistic attitude.

It was a revolt against mainstream Hollywood filmmaking, but it also rejected the slick imagery of the French New Wave.

Most important of all: independent cinema actually existed in America again!

Get ready to uncover the raw energy that fueled a cinematic rebellion.

No Wave Cinema

What Is No Wave Cinema?

No Wave Cinema emerged in the late 1970s and early 1980s as part of the broader No Wave movement in New York City, which included music, art, and film.

This film movement was characterized by its low-budget, avant-garde approach, and its rejection of conventional narrative structures and commercial cinema.

No Wave films were often experimental, raw, and shot on minimal budgets, reflecting the DIY ethos of the movement.

Filmmakers associated with No Wave Cinema, like Jim Jarmusch and Amos Poe, used the medium to explore themes of urban life, alienation, and the underground culture of New York City at the time.

Origins Of No Wave Cinema

The seeds of No Wave Cinema were sown in the economic desolation and cultural ferment of late 1970s New York.

This was a city on the brink – bankrupt, riddled with crime, yet vibrantly creative.

Out of this turmoil emerged a new breed of filmmakers, who, with little money but abundant passion, began crafting works that would defy the norms of traditional filmmaking.

In this context, No Wave was less a coherent movement and more a collective ethos.

Artists and musicians who thrived in venues like CBGB and Max’s Kansas City started to cross-pollinate with avant-garde filmmakers.

Together, they created an environment where conventional narrative structures were discarded in favor of a raw and unfiltered approach to storytelling.

Films such as Unmade Beds and Rome ’78 serve as prime examples.

Key elements that defined No Wave Cinema included:

- DIY production techniques,

- Direct collaboration with artists from other disciplines,

- A focus on gritty urban life,

- An embrace of experimental storytelling.

No Wave’s DNA can be traced back to various influential forerunners.

The confrontational art of the French New Wave, the improvisational energy of jazz, and the gritty reality of Italian Neorealism all played their part in shaping this bold cinematic language.

Yet, Even though these influences, No Wave Cinema stood apart for its uncompromising vision and its root in the unique socio-cultural landscape of New York City at the time.

Key Figures In The No Wave Cinema Movement

We recognize that the No Wave Cinema movement was driven by a few pivotal creators whose innovation and boldness left an indelible mark on the film landscape.

Among them stood Jim Jarmusch, whose minimalist style in Stranger Than Paradise paved the way for future independent filmmakers.

We also can’t forget Amos Poe, a filmmaker famous for The Foreigner and Unmade Beds, which effortlessly captured the gritty aesthetic of the movement.

Another name synonymous with No Wave is Lydia Lunch, not just for her musicianship but also for her magnetic presence in The Offenders.

Beth B and Scott B, with their film Black Box, brought to the screen a convergence of punk art and cinema that challenged and inspired audiences.

The collaborative nature of No Wave extended to visual artists, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, who appeared in Downtown 81, showcasing the symbiosis between the movement and New York’s broader artistic scene.

Sara Driver’s involvement in You Are Not I demonstrated the movement’s intricate storytelling capabilities.

James Nares’ Rome ’78 was a notable foray into the fictional past, proving the movement was not just limited to contemporary urban themes.

Lizzie Borden broke new ground with Born in Flames, exploring feminist themes through a dystopian lens.

Their collective efforts underscored No Wave’s indifference to conventional cinematic norms, while their diverse backgrounds provided a tapestry of creativity that kept the movement ever-fresh.

These filmmakers embraced lo-fi aesthetics and ambivalent narratives, often portraying the city as a character in its own right.

This raw unpolished approach not only breathed life into their projects but also influenced countless others in the realm of storytelling, video art, and beyond.

The avant-garde nature of No Wave films means that even today, they continue to be dissected and analyzed for their contributions not only to cinema history but also to the cultural discourse of their times.

The legacy of No Wave Cinema remains apparent, with many modern indie filmmakers citing the movement as a seminal influence on their work.

Characteristics Of No Wave Cinema

No Wave Cinema didn’t just push boundaries – it intentionally crossed them, cultivating a style fiercely independent and markedly different from mainstream film.

Here are some defining traits of this avant-garde movement:

- Lo-fi Production Values – Resources were limited, so filmmakers made do with what they had. This often meant shooting on 16mm or 8mm film, or even video, leading to a gritty, unpolished look that became synonymous with the genre.

- Non-Professional Actors – Much like the production values, the cast often consisted of friends or artists from other disciplines, injecting raw authenticity into the performances.

The narratives in No Wave Cinema were often disjointed or non-linear, defying classical storytelling conventions.

This resulted in films that were as challenging to understand as they were to watch.

Directors like Amos Poe and Jim Jarmusch crafted stories that felt more like slices of life than carefully constructed narratives.

The visual aesthetics were marked by an urban sensibility that captured the city’s decaying landscape.

Films like Permanant Vacation and Unmade Beds showcased streetscapes that were characters in their own right – gritty, stark, and undeniably real.

Soundtracks were also a crucial element, typically featuring music from contemporary No Wave bands.

This synergy between No Wave Cinema and the concurrent music movement added another layer of cultural resonance to the films.

No Wave Cinema remains an integral part of film history not merely for its distinct style but for its enduring influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers.

The do-it-yourself ethos and experimental narrative structures continue to resonate within the indie film scene, proving that the impact of No Wave Cinema extends well beyond its era.

Influence Of No Wave Cinema On The Indie Film Scene

No Wave Cinema left an indelible mark on the indie film scene that still resonates with today’s filmmakers.

It’s often cited as a rebellious movement that set the stage for the independent film boom of the 1990s.

This ripple effect showcased the possibilities that come with stepping outside standard industry practices.

As a film history and theory experts with a keen interest in film movements, we’ve observed how No Wave Cinema has emboldened directors and screenwriters to prioritize artistic vision over commercial appeal.

The movement championed a do-it-yourself ethos that’s become foundational in the indie scene.

Here are several key influences of No Wave Cinema:

- Innovation in Storytelling – No Wave filmmakers explored non-linear narratives and ambiguous endings, trends that we see heavily embraced in independent cinema today.

- Lo-Fi Aesthetic – The raw aesthetics of No Wave prompted indie filmmakers to recognize the charm of low-budget production, bringing forth a wave of films that celebrate imperfections.

- Use of Non-Professional Actors – This practice opened doors for a more authentic style of performance in indie films, where character and realness often trump polished acting skills.

Directors like Jim Jarmusch, with films such as Stranger Than Paradise, and Richard Linklater, with his early work like Slacker, both embody No Wave’s nonconformity and resourcefulness.

They’ve challenged and inspired independent filmmakers to craft unique stories, regardless of budget constraints or mainstream trends.

The aesthetic and thematic sensibilities of No Wave films continue to course through the veins of independent cinema.

This movement has given filmmakers permission to question and redefine the boundaries of film narrative and style.

In our pursuit of understanding filmmaking, it’s apparent that No Wave Cinema has become a benchmark of creative freedom, encouraging an environment where films can be as diverse as the visionaries behind the camera.

What Is No Wave Cinema – Wrap Up

We’ve delved deep into the heart of No Wave Cinema, uncovering the movement’s raw power and enduring influence.

Our journey through the gritty streets of 1970s New York has shown us how these pioneering filmmakers crafted a new cinematic language.

Their legacy lives on, inspiring a generation of indie filmmakers to embrace the beauty of the unconventional.

They’ve taught us that creativity isn’t bound by budgets or mainstream expectations but thrives on the freedom to tell authentic stories.

No Wave Cinema didn’t just capture a moment in time—it ignited a spark that continues to illuminate the path for independent cinema.

Let’s carry this spirit forward, celebrating the bold and the experimental in film, just as the No Wave auteurs did.

Here’s to the next wave of filmmakers who’ll push boundaries and challenge us with their visions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is No Wave Cinema?

No Wave Cinema was an underground film movement that emerged in the late 1970s in New York, known for its raw storytelling, lo-fi aesthetics, and unconventional narratives, which starkly contrasted mainstream cinema.

Who Were The Key Figures In The No Wave Cinema Movement?

Key figures in No Wave Cinema include Jim Jarmusch, Amos Poe, Lydia Lunch, Beth B, Scott B, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sara Driver, James Nares, and Lizzie Borden, among others.

These filmmakers are credited with shaping the movement’s style and ethos.

How Did No Wave Cinema Differ From Conventional Filmmaking?

No Wave Cinema discarded conventional narrative structures, embraced lo-fi production values, utilized non-professional actors, and often showcased New York City’s decaying urban landscape within its aesthetics.

What Impact Did No Wave Cinema Have On Modern Indie Filmmakers?

No Wave Cinema had a significant impact on modern indie filmmakers, many of whom cite the movement as an influence.

It introduced a DIY ethos and showed that films could be made outside of standard industry practices, which paved the way for the independent film boom of the 1990s.

How Does No Wave Cinema Continue To Influence Films Today?

The movement’s legacy lives on in its challenge to narrative and stylistic norms, encouraging filmmakers to explore non-linear storytelling, authentic performances, and resourceful filmmaking, regardless of budget constraints.

It has become a benchmark of creative freedom in the film industry.