- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

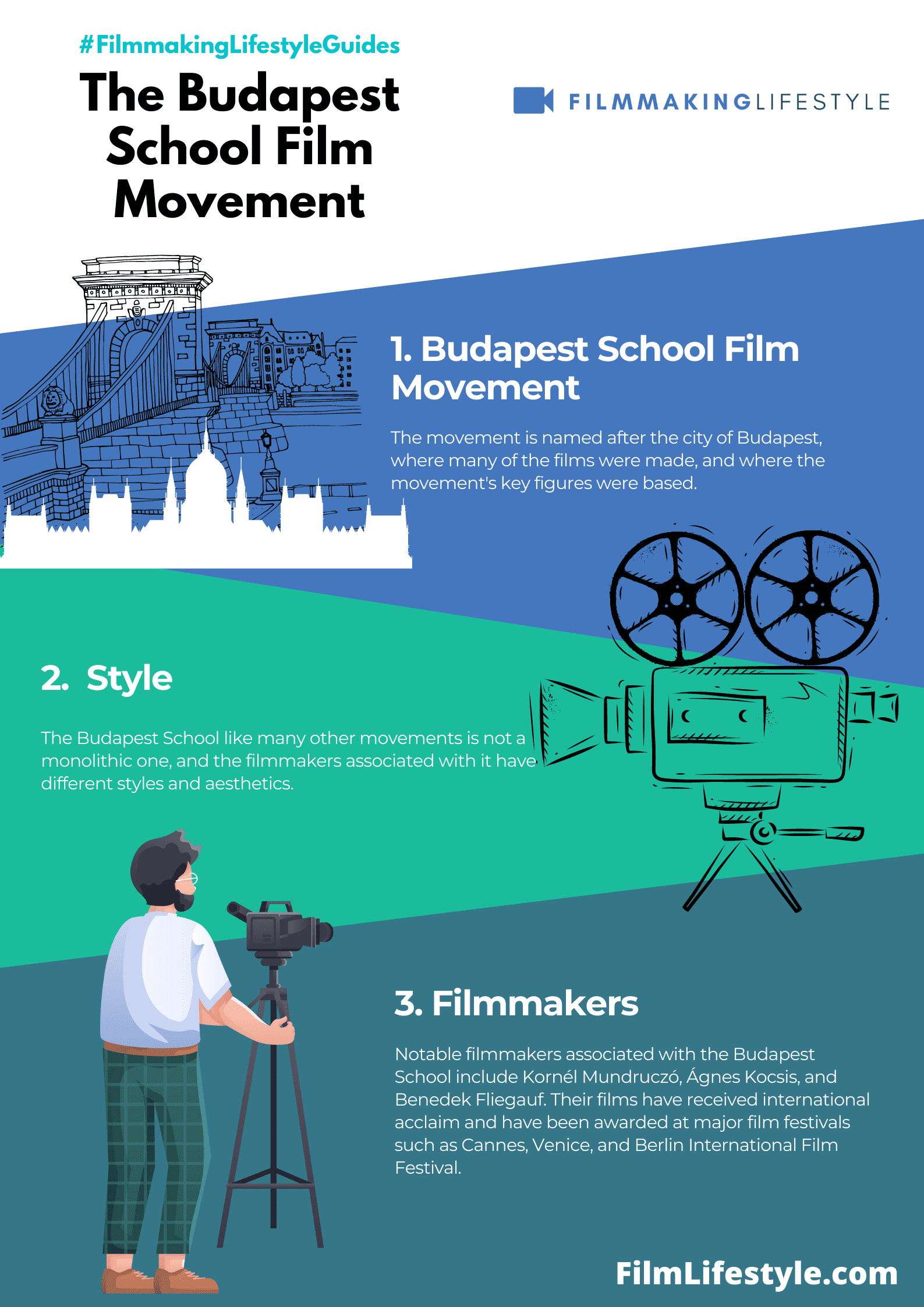

- The Budapest School

The Budapest School Film Movement is a cinematic revolution that emerged from Hungary, challenging traditional storytelling with its unique voice.

We’ll uncover the roots and impact of this movement, which thrived in the 1960s and 1970s, showcasing a blend of innovation and resistance.

Join us as we explore how these filmmakers defied political and artistic constraints, creating a legacy that resonates in cinema today.

We’re about to jump into the defining characteristics of the Budapest School and its influence on contemporary filmmaking.

Budapest School Film Movement

What Is the Budapest School Film Movement?

The Budapest School was a group of filmmakers and theorists in Hungary in the 1970s, known for their experimental and philosophical approach to cinema.

Influenced by Marxist and psychoanalytic theory, their work often explored the relationship between individual subjectivity, social structures, and cinema.

This movement, while not as widely recognized internationally as some other film movements, played a significant role in the Hungarian film scene and had broader implications in the field of cinema studies.

Origins Of The Budapest School Film Movement

The seeds of the Budapest School Film Movement were sown in the politically turbulent environment of 1960s Hungary.

Directors like Miklós Jancsó redefined cinema with their revolutionary ideas, forever altering the way stories were told on screen.

Their work took inspiration from French New Wave directors like Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut and their penchant for iconoclastic storytelling and visual experimentation.

This movement arose as a form of resistance both to the political regime of the time and to the rigid structures of traditional filmmaking.

In an industry that was heavily state-controlled, these Hungarian filmmakers pushed the boundaries of narrative and aesthetic expression.

Films under this movement tended to feature:

- Long takes and minimal editing to preserve temporal continuity,

- A focus on historical and political topics, often presented allegorically,

- Use of non-professional actors to enhance authenticity.

The Hungarian Film School, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s, served as a breeding ground for the talent behind the Budapest School.

Professors and students embraced the idea that film could be more than entertainment; it could be an agent of change.

Key figures of the movement like István Szabó emerged from this institution, bringing a fresh perspective to Hungarian cinema and beyond.

Educational exchanges and film festivals played a crucial role in the cross-pollination of ideas that fueled the movement’s growth.

Directors educated or influenced by the Budapest School took their skills across Europe, disseminating the unique style that had been honed behind the Iron Curtain.

This cultural diffusion led to collaborations and innovations that echoed far beyond Hungary’s borders, deeply influencing international film discourse.

Key Characteristics Of The Budapest School

Embracing Reality Through Cinematography

The Budapest School’s approach to cinematography is one of its most defining aspects.

Natural lighting and on-location shooting were favored, blurring the line between documentary and fiction.

This method allowed for an authentic representation of Hungarian life, capturing the essence of reality without the gloss of studio production.

Narrative Innovation

In terms of narrative, the Budapest School filmmakers often adopted a non-linear storytelling approach, challenging viewers to engage more deeply with the unfolding story.

A prime example of this can be seen in István Szabó’s Father, where fragmented time and memory play crucial roles in the narrative structure.

The Use Of Sound

Our examination of the Budapest School would be incomplete without addressing its innovative use of sound.

The integration of diegetic sounds – noises present within the world of the film – was used to heighten the realism and immerse the audience in the environment depicted on screen.

Collaboration And Improvisation

Central to the filmmaking process was the:

- Use of non-professional actors,

- Encouragement of improvisation.

These elements brought a freshness to the performances and a verisimilitude that could not be easily achieved with conventional actors and scripted dialogue.

Political Subtexts

finally, Even though the oppressive political climate of the time, Budapest School films often contained subtle political subtexts.

Through allegory and metaphor, filmmakers conveyed critiques of the regime, risking censorship or worse for the sake of artistic expression and social commentary.

As we jump further into this compelling film movement, one can’t help but admire the resilience and ingenuity of its proponents.

Their contributions to the film industry continue to resonate, influencing filmmakers and captivating audiences around the globe.

Political And Artistic Resistance

As a community deeply invested in the historical context and theoretical frameworks of film movements, we recognize that the Budapest School Film Movement wasn’t just a creative awakening – it was a political stance.

Against the backdrop of a repressive regime, these films served as an understated form of rebellion that delicately balanced artistry with subversion.

Directors and writers used their craft as a vehicle for dissent, threading subtle critiques of the establishment through the fabric of their narratives.

The power of these films lay in their ability to convey messages beneath the surface.

While overt political messaging could invite censorship or worse, the Budapest School filmmakers employed a range of techniques to ensure their voices were heard:

- Symbolism was woven throughout, offering a deeper layer of meaning.

- Allegories obfuscated direct attacks on government policies.

- Understated dialogue carried weighty social and political implications.

In outlining the movement’s resistance, we shed light on the creative guerrilla tactics honed by these artists.

Their works, like The Witness and Father, weren’t just films – they were acts of artistic bravery.

Scenes that might seem innocuous to the untrained eye were often loaded with a sharp critique of the socio-political landscape.

This strategic ambiguity allowed the filmmakers to navigate the treacherous waters of government scrutiny while still sharing their views with audiences both at home and internationally.

Our focus on film and video through Filmmaking Lifestyle places us in a unique position to appreciate the nuances of the Budapest School’s approach to political resistance.

Their legacy is not only one of cinematic innovation but also an enduring symbol of the strength of artistic expression in the face of adversity.

The Legacy Of The Budapest School

The Budapest School Film Movement left an indelible mark on the cinematic landscape.

Not only did it redefine narrative structure and aesthetics, but it also paved the way for future Hungarian filmmakers to carry forward the torch of innovative storytelling.

The students and faculty of the Hungarian Film School, who were central to the core of the Budapest School, laid the groundwork for film as a means of personal and political expression.

In examining the reach of the Budapest School, it’s important to highlight the distinct features that continue to influence contemporary cinema:

- The use of long takes and minimal editing techniques to create a sense of realism and immediacy.

- Embracing non-linear storytelling, allowing for more complex and layered narratives.

- The integration of political subtexts providing a commentary on the socio-political climate of the time.

These elements converged to produce films that remain poignant and relevant.

Films like Mephisto and The Red and the White serve as poignant reminders of the movement’s impact, showcasing how the Budapest School’s themes and techniques resonated beyond Hungary’s borders.

also, the ethos of the movement inspires filmmakers worldwide who embrace a human-centric approach to storytelling, capturing the subtleties and intricacies of human experience.

As educators and mentors, the leading figures of the Budapest School influenced generations of filmmakers.

They taught students to view film as a potent tool for cultural commentary – an ethos that has carried into modern-day film education.

This educational aspect ensures that the Budapest School’s revolutionary spirit survives, as new filmmakers are continually exposed to their groundbreaking vision.

Contemporary Filmmaking Influences

The Budapest School’s imprint on contemporary cinema cannot be understated.

We see its influence in films that prioritize authentic performances and embrace a more fluid form of storytelling.

Directors such as Béla Tarr, who attended the Hungarian Film School, perpetuate the legacy through their critically acclaimed works.

For instance, Satantango draws heavily from the School’s use of long takes and minimalism to deliver a mesmerizing narrative experience.

Modern filmmaking continues to evolve with technological advancements, yet the Budapest School’s principles still resonate.

The movement’s emphasis on deep character exploration and the blending of fiction with reality have inspired independent filmmakers around the globe.

Such methods are evident in the works of Gus Van Sant and the mumblecore movement, characterized by:

- Naturalistic dialogue and performances,

- Focus on character relationships,

- Minimalist production values.

The utilization of non-linear narratives has also been a significant contribution to current film editing techniques.

The fragmented storytelling seen in Christopher Nolan’s Memento and the exploration of time in Pulp Fiction by Quentin Tarantino can trace their roots back to the innovative approaches of the Budapest School.

These films challenge viewers to engage with the plot on a more intricate level, a clear nod to the intricate narrative structures pioneered by Hungarian filmmakers.

Beyond narrative and dialogue, the School’s subtle use of politics in film is more pertinent than ever.

In an era where filmmakers grapple with socio-political themes, the Budapest School’s tactful and allegorical methods pave the way for stories that comment on society with nuance and multiple layers of interpretation.

This is especially relevant in films that address contemporary issues while avoiding overt polemicism, requiring a balance that Hungarian directors mastered decades ago.

What Is The Budapest School Film Movement – Wrap Up

We’ve traced the Budapest School’s indelible mark on the cinematic landscape, recognizing its role in redefining narrative and aesthetic norms.

Their legacy endures in contemporary cinema, as current filmmakers draw from their innovative storytelling and authentic character portrayals.

The School’s principles continue to resonate, from non-linear narratives to the subtle infusion of political commentary in film.

As we look to the future of cinema, it’s clear that the Budapest School’s revolutionary spirit and its contributions to film education will continue to inspire and shape the art of filmmaking for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was The Budapest School Film Movement?

The Budapest School Film Movement was a group of filmmakers in Hungary during the 1960s, known for challenging traditional filmmaking and incorporating new narratives, aesthetics, and political subtexts.

Who Were The Main Figures Of The Budapest School?

István Szabó is one of the key figures of the Budapest School, which also included many other talented filmmakers who studied at the Hungarian Film School.

What Techniques Were Characteristic Of The Budapest School Filmmakers?

The Budapest School filmmakers were known for their use of long takes, minimal editing, non-professional actors, non-linear storytelling, innovative sound, and political themes expressed through allegory and symbolism.

How Did The Budapest School Influence International Cinema?

The Budapest School influenced international cinema by showcasing their unique style at film festivals and through educational exchanges, leaving a lasting impact on storytelling, aesthetics, and political discourse in films.

Did The Budapest School Have An Impact On Modern Filmmakers?

Yes, modern filmmakers are influenced by the Budapest School, especially in terms of authentic performance, fluid storytelling, non-linear narratives, and the use of film as political resistance.

What Legacy Did The Budapest School Leave Behind?

The Budapest School’s legacy includes revolutionary narrative structures, a fresh aesthetic approach, and the empowerment of artists to express themselves in the face of adversity.

Their teachings continue to inspire new generations in film education.