- 1960s-70s Film Movements

- British New Wave

- French New Wave

- Cinéma Vérité

- Third Cinema

- New German Cinema

- New Hollywood

- Japanese New Wave

- Cinema Novo

- Czech New Wave

- Movie Brats

- LA Rebellion

- Australian New Wave

- Yugoslav Black Wave

- Grupo Cine Liberación

- Cinema Da Boca Do Lixo

- Cinema Of Moral Anxiety

- Soviet Parallel Cinema

- The Budapest School

Ever wondered what shook the foundations of cinema in the 1950s and 60s? That’s right, it was the French New Wave, a movement that redefined film as we know it.

We’re about to dive into the heart of this revolutionary period that brought us iconic directors and timeless classics.

We’ll explore the hallmarks of French New Wave, from its jump cuts to existential themes, and how it turned the filmmaking rulebook on its head.

If you’re a film buff or just love a dash of culture, stick around; this is one wave you won’t want to miss riding.

FRENCH NEW WAVE

What Is The French New Wave?

The French New Wave, known as “Nouvelle Vague,” was a cinematic movement that emerged in France during the late 1950s and 1960s.

It represented a radical departure from traditional filmmaking conventions, characterized by its innovative storytelling, visual style, and the way it challenged the norms of the film industry.

Pioneered by young filmmakers who were often critics for the influential film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, the French New Wave rejected the classical narrative structure and instead embraced a more free-form and improvisational approach.

Directors like Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol became synonymous with the movement.

What Is The French New Wave?

At its core, the French New Wave was a radical departure from the existing norms and techniques of filmmaking.

The movement emerged out of a rising disillusionment with the traditional French cinema, which many of the Nouvelle Vague directors considered to be overly literary and bound by rigid conventions.

Truffaut, Godard, and their peers embarked on a journey to create films that resembled the reality they observed and experienced.

They were heavily influenced by their backgrounds as film critics for the influential magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, where they championed the works of then-underappreciated directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks.

These earlier filmmakers’ emphasis on personal vision and distinctive styles resonated with the young French directors, fueling their desire to innovate.

The films produced during this time were marked by experimentation and a desire to provoke viewers into a new understanding of what cinema could be.

The filmmakers employed techniques like jump cuts, handheld camera work, and natural lighting, lending a documentary-like feel to their films.

This sense of realism was further enhanced by the use of on-location shooting and the casting of non-professional actors or fresh faces, who brought an authenticity that traditional stage-trained actors often lacked.

Narratively, French New Wave films often broke from linear storytelling, choosing instead to embrace ambiguity and complexity.

They eschewed plot-heavy stories for character-driven pieces, focusing on the human experience and the existential struggles within.

Themes were as diverse as the directors themselves, ranging from social commentary to profound introspection about love, life, and the very act of filmmaking.

If you’re interested in learning more about the French New Wave film movement, check out our in-depth profile and explore our comprehensive timeline of film movements to see where it fits in cinema history.

The influence of these cinematic innovations cannot be overstated. They’ve left a lasting legacy, inspiring filmmakers around the globe and shaping the very way we think about storytelling in film.

As I jump into the specific characteristics of the French New Wave, it’s clear why this period represents a fundamental shift in the art of cinema.

The term French New Wave has been used to describe an independent film movement from France in the 1960s, but this article will focus on films made during the original period of 1959-1964.

Films like Breathless (1960) were groundbreaking because they rejected traditional cinematic techniques such as deep focus cinematography or linear narratives for more experimental ones that included jump cuts, hand-held camera shots, natural lighting, and location shooting.

These new techniques allowed filmmakers to break away from what had come before them and create something entirely new. Something fresh.

The French New Wave was characterized by:

- an informal style of filmmaking,

- improvisation during shooting,

- hand-held cameras for ‘natural’ shots, and

- experimental editing, often using ‘jump cuts.’

The films are noted for their innovative approaches to:

- narrative,

- cinematography,

- use of sound,

- dialogue delivery (often naturalistic), and

- their breaking away from traditional Hollywood conventions such as the three-act structure or omniscient narrator.

Key Directors and Films of the French New Wave

The pioneers of the French New Wave, masters like François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, charted new territory in their field. These iconoclasts left an indelible mark, not just on French cinema, but on global filmmaking as a whole.

Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (Les Quatre Cents Coups) released in 1959, stands as a seminal work of the movement. It’s his autobiographical tale which introduced audiences to Antoine Doinel, a character that Truffaut would revisit in his subsequent works.

Truffaut’s adeptness at blending heartfelt storytelling with innovative film techniques established him as a crucial figure within Nouvelle Vague.

Godard, another trailblazer, shattered conventional film grammar with his debut Breathless (À Bout de Souffle), also from 1959. This film embraced a loose form of editing, including the now-famous jump cuts, and casual dialogues, which were revolutionary at the time.

Godard’s work is often celebrated for its rebellious spirit and intellectual engagement with contemporary issues.

Apart from these, several other directors played significant roles in the New Wave movement. Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Agnès Varda are worth mentioning.

Varda, with her film Cléo from 5 to 7 scrutinized the life of a woman in real-time, creating a poignant narrative interwoven with philosophical contemplation.

Here are some of the key films from these directors that were landmarks of the French New Wave:

| Director | Notable Films |

|---|---|

| François Truffaut | The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player |

| Jean-Luc Godard | Breathless, Vivre Sa Vie |

| Claude Chabrol | Le Beau Serge, Les Cousins |

| Éric Rohmer | My Night at Maud’s |

| Jacques Rivette | Paris Belongs to Us |

| Agnès Varda | Cléo from 5 to 7, Le Bonheur |

The resonance of these films is not limited to the originality of their storytelling or the defiance of classical styles; they signify a complete overhaul in the understanding of what cinema can achieve.

Best French New Wave Films

The French New Wave, or La Nouvelle Vague in its native tongue, is a film movement that took place largely during the late 1950s to late 1960s.

While it was initially seen as a rejection of traditional Hollywood cinema, it has since been embraced for its ability to shock audiences with its innovative techniques.

A key feature of the French New Wave is their preference for shooting on location and using natural lighting rather than relying on studio sets or artificial light sources.

By filming outside instead of inside studios, they were able to capture life as it actually happens; something that had never been done before in movies at this scale.

This technique also allowed them to use more improvisation from actors because they weren’t confined by set rules and regulations like other films.

Let’s look at what we believe to be the best French New Wave films.

Breathless (A bout de souffle) (1960)

Breathless

Wild! Violent! Outspoken and Honest!

1960 • 1h 30min • ★ 7.523/10 • France

Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard

Cast: Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg, Daniel Boulanger, Henri-Jacques Huet, Roger Hanin

A small-time thief steals a car and impulsively murders a motorcycle policeman. Wanted by the authorities, he attempts to persuade a girl to run away to Italy with him.

Breathless (A bout de souffle) is a French New Wave film directed by Jean-Luc Godard and released in 1960.

The film is considered a masterpiece of modern cinema and has been influential on many subsequent films.

The film follows the story of Michel Poiccard, a small-time criminal and car thief who is on the run from the police after killing a cop.

Along the way, he meets an American student named Patricia and the two begin a tumultuous relationship.

As Michel tries to evade the police, he becomes increasingly desperate and unstable, leading to a tragic and unforgettable conclusion.

Breathless is a film that is as much about style as it is about substance. Godard’s use of jump cuts, hand-held cameras, and non-linear storytelling techniques broke new ground in the world of cinema and have had a lasting impact on filmmakers around the world.

The film also features a memorable soundtrack, with jazz music playing throughout the film.

The performances by Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg are both excellent, with their on-screen chemistry and interactions helping to bring the characters to life.

The film’s themes of love, crime, and the pursuit of freedom are explored in a unique and thought-provoking way, making it a must-see for anyone interested in the history of cinema.

- Spanish (Subtitle)

- English (Publication Language)

- Audience Rating: NC-17 (Adults Only)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

A film for all the young lovers of the world.

1964 • 1h 32min • ★ 7.4/10 • France

Directed by: Jacques Demy

Cast: Catherine Deneuve, Nino Castelnuovo, Anne Vernon, Mireille Perrey, Marc Michel

This simple romantic tragedy begins in 1957. Guy Foucher, a 20-year-old French auto mechanic, has fallen in love with 17-year-old Geneviève Emery, an employee in her widowed mother's chic but financially embattled umbrella shop. On the evening before Guy is to leave for a two-year tour of combat in Algeria, he and Geneviève make love. She becomes pregnant and must choose between waiting for Guy's return or accepting an offer of marriage from a wealthy diamond merchant.

“The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” is a French musical film directed by Jacques Demy and starring Catherine Deneuve and Nino Castelnuovo.

The film is known for its vibrant colors and the use of sung dialogue throughout the film.

The story is set in the late 1950s in Cherbourg, France and follows the romance between 17-year-old Geneviève (Deneuve) and 20-year-old Guy (Castelnuovo).

The two fall deeply in love but their happiness is short-lived when Guy is drafted to fight in the Algerian War.

Geneviève finds out that she is pregnant and must face the reality of raising a child alone.

The film’s use of color and music makes it a visually stunning masterpiece.

The colorful and playful production design adds a whimsical element to the story, while the music composed by Michel Legrand is both memorable and emotional.

The film’s themes of love, loss, and the passing of time are all beautifully depicted.

Catherine Deneuve delivers a standout performance as Geneviève, capturing the innocence and vulnerability of her character with grace.

Nino Castelnuovo also shines as Guy, bringing a genuine sense of longing and passion to his role.

Paris Belongs to Us / Paris nous appartient (1961)

Paris Belongs to Us

1961 • 2h 21min • ★ 6.5/10 • France

Directed by: Jacques Rivette

Cast: Betty Schneider, Giani Esposito, Françoise Prévost, Daniel Crohem, François Maistre

A young woman joins a theatrical troupe where she slowly believes that the director is involved with a secret group and that he is in grave danger.

Paris Belongs to Us (1961) is a thought-provoking and enigmatic film that explores the struggles of a group of young, politically active Parisians in the late 1950s.

Directed by French filmmaker Jacques Rivette, the film is a complex and layered exploration of existentialism, paranoia, and political disillusionment.

The story follows the character of Anne, a young woman who becomes involved in a group of intellectuals and artists who are struggling to find meaning and purpose in their lives.

As the group becomes increasingly consumed by their own anxieties and paranoia, they begin to suspect that they are being targeted by a shadowy conspiracy.

The film is visually striking, with Rivette utilizing the stunning backdrop of Paris to great effect.

The stark black-and-white cinematography creates a moody and atmospheric tone, while the long, static shots and unconventional editing style add to the film’s sense of unease.

The performances are also excellent, with Anne played by the talented Betty Schneider, who gives a nuanced and complex portrayal of a woman caught between her own desires and the pressures of the world around her.

While the film’s themes and narrative can be challenging to follow at times, it is ultimately a rewarding and thought-provoking experience.

Paris Belongs to Us is a masterful exploration of the complexities of human relationships and the struggle for meaning in an uncertain world.

- Paris Belongs To Us (Criterion Collection) - Blu-ray Used Like New

- Betty Schneider, Jean-Claude Brialy (Actors)

- Jacques Rivette (Director)

- English (Subtitle)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Shoot The Piano Player / Tirez sur le pianiste (1960)

Shoot the Piano Player

François Truffaut, Brilliant Director Who Gave You the Award Winning "The 400 Blows", Now Brings to the Screen a Fascinating New Work That Plays in Many Keys...All of Them Delightful!

1960 • 1h 25min • ★ 7.198/10 • France

Directed by: François Truffaut

Cast: Charles Aznavour, Marie Dubois, Nicole Berger, Michèle Mercier, Serge Davri

Charlie is a former classical pianist who has changed his name and now plays jazz in a grimy Paris bar. When Charlie's brothers, Richard and Chico, surface and ask for Charlie's help while on the run from gangsters they have scammed, he aids their escape. Soon Charlie and Lena, a waitress at the same bar, face trouble when the gangsters arrive, looking for his brothers.

Shoot the Piano Player (Tirez sur le pianiste) is a 1960 French New Wave film directed by François Truffaut.

The movie follows Charlie, a former concert pianist who now works as a bar pianist.

Charlie’s life takes a dramatic turn when his criminal brother comes back into his life, and he must navigate dangerous situations to protect his loved ones.

The film is a classic example of the French New Wave movement, characterized by its non-linear plot, use of jump cuts, and overall experimental approach to filmmaking.

The performances are all exceptional, with Charles Aznavour delivering a nuanced portrayal of Charlie, and Marie Dubois bringing a lively energy to her role as Léna, the woman who captures Charlie’s heart.

Truffaut’s direction is masterful, with a blend of humor and tragedy that keeps the audience engaged throughout.

The film is also notable for its use of music, with a memorable score by Georges Delerue and a scene-stealing performance by Charlie’s character on the piano.

- Shoot the Piano Player (1960) ( Tirez sur le pianiste )

- Shoot the Piano Player (1960)

- Tirez sur le pianiste

- Charles Aznavour, Marie Dubois, Daniel Boulanger (Actors)

- Fran?ois Truffaut (Director) - Shoot the Piano Player (1960) ( Tirez sur le pianiste ) (Producer)

Last Year At Marienbad (1961)

Last Year at Marienbad

Extraordinary! Hypnotic! Beautiful! Masterful!

1961 • 1h 35min • ★ 7.422/10 • France

Directed by: Alain Resnais

Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoëff, Françoise Bertin, Luce Garcia-Ville

In a strange and isolated chateau, a man becomes acquainted with a woman and insists that they have met before.

Last Year at Marienbad is a surrealistic French film from 1961, directed by Alain Resnais and written by Alain Robbe-Grillet.

The film is a stunning example of French New Wave cinema, with its non-linear storytelling, stylistic flourishes, and enigmatic themes.

The film takes place at a luxurious chateau in Marienbad, where an unnamed man (Giorgio Albertazzi) attempts to convince a woman (Delphine Seyrig) that they had a romantic encounter the previous year at the same location.

However, the woman repeatedly denies any recollection of their meeting, leading the man to become increasingly desperate and obsessive in his pursuit.

The narrative is intentionally fragmented and disorienting, with scenes and images repeating and morphing into one another in a dreamlike manner.

The film’s cinematography is particularly striking, with elegant long takes and a distinctive use of shadows and reflections.

Last Year at Marienbad is a challenging and unconventional film that demands the viewer’s active engagement and interpretation.

The film’s themes include memory, time, perception, and the nature of reality, and it is left up to the audience to piece together the meaning and significance of the events on screen.

- Last Year at Marienbad (1961) ( L'Année dernière à Marienbad ) ( L'Anno scorso a Marienbad )

- Last Year at Marienbad (1961)

- L'Année dernière à Marienbad

- L'Anno scorso a Marienbad

- Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi, Sacha Pitoëff (Actors)

La jetée (1962)

La Jetée

A man's obsession with an image of his past

1962 • 0h 29min • ★ 7.871/10 • France

Directed by: Chris Marker

Cast: Jean Négroni, Hélène Chatelain, Davos Hanich, Jacques Ledoux, André Heinrich

A man confronts his past during an experiment that attempts to find a solution to the problems of a post-apocalyptic world caused by a world war.

La jetée is a French science fiction short film directed by Chris Marker.

It tells the story of a man who has been subjected to time travel experiments in a post-apocalyptic world.

The film is unique in that it consists almost entirely of still images and voice-over narration, with only one brief sequence of live-action footage.

The story follows the protagonist, a man who has a vivid memory from his childhood of seeing a woman on a pier at an airport just before witnessing a traumatic event.

As an adult, he is chosen to participate in a time travel experiment in order to help his fellow survivors.

The experiment involves sending him back in time to the moment he saw the woman on the pier, in the hope that he can help prevent the catastrophe that followed.

The film’s use of still images creates a haunting and dreamlike atmosphere, and the voice-over narration adds to the sense of isolation and desperation felt by the characters.

The film explores themes of memory, time, and the human condition in a post-apocalyptic world.

La jetée is widely regarded as a classic of French cinema and an important film in the science fiction genre.

Its influence can be seen in the works of other filmmakers, such as Terry Gilliam’s Twelve Monkeys.

While its experimental style may not be for everyone, it is a fascinating and thought-provoking work that has stood the test of time.

- English (Subtitle)

Jules et Jim (1962)

Jules and Jim

A Hymn to Life and Love

1962 • 1h 46min • ★ 7.563/10 • France

Directed by: François Truffaut

Cast: Henri Serre, Oskar Werner, Jeanne Moreau, Marie Dubois, Sabine Haudepin

In the carefree days before World War I, introverted Austrian author Jules strikes up a friendship with the exuberant Frenchman Jim and both men fall for the impulsive and beautiful Catherine.

Jules et Jim is a French New Wave film directed by François Truffaut, based on a semi-autobiographical novel by Henri-Pierre Roché.

The film follows the lives of two friends, Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre), who both fall in love with the free-spirited Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) in pre-World War I Paris.

The film is a unique exploration of love, friendship, and the complexities of relationships.

Jules and Jim share a deep bond, and their friendship is tested when they both fall in love with Catherine.

The three embark on a tumultuous love affair, with Catherine constantly seeking new experiences and pushing the boundaries of what is considered acceptable in society.

The film takes us on a journey through their lives, as they navigate through World War I, Catherine’s unpredictable behavior, and their changing feelings towards each other.

Truffaut’s direction and the performances of the three leads make this film a masterpiece.

The use of voice-over narration, freeze frames, and non-linear storytelling techniques were groundbreaking at the time, and influenced many filmmakers in the years to come.

Jeanne Moreau’s portrayal of Catherine is particularly captivating, as she perfectly embodies the essence of a free-spirited, independent woman who refuses to conform to societal norms.

Jules et Jim is a beautifully shot film that captures the essence of Paris and the bohemian lifestyle of the time.

The film’s themes of love and friendship, and the exploration of the complexities of human relationships, make it a timeless classic.

Jules et Jim is a must-see for anyone interested in French New Wave cinema, or for those who appreciate a great love story.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=x5IAYIUKTaI

- The disk has English audio and subtitles.

- Polish Release, cover may contain Polish text/markings. The disk has English audio and subtitles.

- English (Subtitle)

Pierrot le fou (1965)

Pierrot le Fou

You've met the tame Godard, the love Godard, the think Godard, ...now meet the wild Godard!

1965 • 1h 50min • ★ 7.4/10 • France

Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard

Cast: Jean-Paul Belmondo, Anna Karina, Graziella Galvani, Aicha Abadir, Henri Attal

Pierrot escapes his boring society and travels from Paris to the Mediterranean Sea with Marianne, a girl chased by hit-men from Algeria. They lead an unorthodox life, always on the run.

“Pierrot le fou” is a French film directed by Jean-Luc Godard.

The movie is a combination of a love story and a crime thriller, and is known for its stylistic experimentation and its use of vibrant colors.

The film stars Jean-Paul Belmondo as Ferdinand, a man who is tired of his mundane life and decides to leave his wife and family to go on a road trip with Marianne, played by Anna Karina.

Marianne is being chased by gangsters and has stolen money from them, which puts Ferdinand in danger as well.

Throughout the film, Godard employs a variety of techniques, such as jump cuts, voice-over narration, and a non-linear storyline.

The use of vibrant colors, including bright blues, pinks, and greens, also contributes to the film’s unique visual style.

The chemistry between Belmondo and Karina is one of the highlights of the film, as they play off each other well and their dialogue is often witty and playful.

The movie also features an eclectic soundtrack, which ranges from classical music to rock and roll.

- Graziella Galvani, Dirk Sanders, Raymond Devos (Actors)

- Jean-Luc Godard (Director) - Georges de Beauregard (Producer)

- English (Subtitle)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Contempt (Le mépris) (1963)

Contempt

More bold! More brazen! And much, much more Bardot!

1963 • 1h 43min • ★ 7.087/10 • France

Directed by: Jean-Luc Godard

Cast: Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, Jack Palance, Giorgia Moll, Fritz Lang

A philistine in the art film business, Jeremy Prokosch is a producer unhappy with the work of his director. Prokosch has hired Fritz Lang to direct an adaptation of "The Odyssey," but when it seems that the legendary filmmaker is making a picture destined to bomb at the box office, he brings in a screenwriter to energize the script. The professional intersects with the personal when a rift develops between the writer and his wife.

“Contempt” (Le mépris) is a French-Italian drama film directed by Jean-Luc Godard, starring Brigitte Bardot, Michel Piccoli, and Jack Palance.

The film is based on the novel “Il disprezzo” by Italian writer Alberto Moravia.

The story follows a screenwriter, Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli), who is hired to adapt Homer’s “Odyssey” into a movie script by a wealthy American producer, Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance).

Paul’s relationship with his wife Camille (Brigitte Bardot) becomes strained as he becomes more involved in the movie business and starts to succumb to the superficiality and greed of the Hollywood system.

At its core, “Contempt” is a film about the struggles of artistic integrity in the face of commercialism.

The film is known for its stunning visuals, with Godard’s use of color and composition creating a sense of unease and detachment in the audience.

The performances are also exceptional, with Bardot and Piccoli delivering nuanced and complex portrayals of their characters.

Hiroshima, My Love (1959)

Hiroshima Mon Amour

From the measureless depths of a woman's emotions...

1959 • 1h 32min • ★ 7.693/10 • France

Directed by: Alain Resnais

Cast: Emmanuelle Riva, Eiji Okada, Stella Dassas, Pierre Barbaud, Bernard Fresson

The deep conversation between a Japanese architect and a French actress forms the basis of this celebrated French film, considered one of the vanguard productions of the French New Wave. Set in Hiroshima after the end of World War II, the couple -- lovers turned friends -- recount, over many hours, previous romances and life experiences. The two intertwine their stories about the past with pondering the devastation wrought by the atomic bomb dropped on the city.

“Hiroshima, My Love” is a French film directed by Alain Resnais. The film is a poignant exploration of memory, love, and loss in the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The story follows a French actress, Elle (Emmanuelle Riva), who travels to Hiroshima to shoot a film about peace.

While there, she meets a Japanese architect, Lui (Eiji Okada), and the two begin a passionate love affair.

However, as they explore their feelings for each other, they confront the memories and traumas of their respective pasts, particularly Elle’s painful experiences during World War II in France.

The film’s nonlinear narrative structure, jump cuts, and use of archival footage give it a distinctive and experimental feel.

It masterfully weaves together past and present, fiction and reality, to create a deeply affecting exploration of the human condition.

The cinematography by Michio Takahashi captures the beauty of Hiroshima and its devastation, creating a powerful visual backdrop for the characters’ emotions.

The film’s haunting score by Georges Delerue perfectly complements the melancholic mood of the story.

- Shrink-wrapped

- Emmanuelle Riva, Eiji Okada (Actors)

- Alain Resnais (Director)

- English (Subtitle)

- English (Publication Language)

Cléo From 5 to 7 (1962)

Cléo from 5 to 7

The whole world... has made an appointment with...

1962 • 1h 30min • ★ 7.683/10 • France

Directed by: Agnès Varda

Cast: Corinne Marchand, Antoine Bourseiller, Dominique Davray, Dorothée Blanck, Michel Legrand

Agnès Varda eloquently captures Paris in the sixties with this real-time portrait of a singer set adrift in the city as she awaits test results of a biopsy. A chronicle of the minutes of one woman’s life, Cléo from 5 to 7 is a spirited mix of vivid vérité and melodrama, featuring a score by Michel Legrand and cameos by Jean-Luc Godard and Anna Karina.

Cléo from 5 to 7 is a French film released in 1962 and directed by Agnès Varda.

The film follows the life of a young singer named Cléo, who is awaiting the results of a medical test that could reveal a serious illness.

The film takes place over the course of two hours in real-time as Cléo wanders through Paris, encountering various characters and experiencing a range of emotions.

The film is a poignant exploration of mortality and the human condition, as Cléo grapples with the prospect of her own mortality and the fragility of life.

The film is also a commentary on the role of women in society, as Cléo struggles to find her place in a world that often values women only for their beauty and youth.

The cinematography in the film is striking, with Varda using a variety of techniques to convey Cléo’s perspective and emotions.

The film also features a memorable soundtrack, with original songs by Michel Legrand.

Cléo from 5 to 7 is a masterpiece of French New Wave cinema, with Varda’s direction and Corinne Marchand’s performance as Cléo both receiving critical acclaim.

The film remains a classic of French cinema and a must-see for fans of art house cinema.

The 400 Blows (1959)

The 400 Blows

Angel faces hell-bent for violence.

1959 • 1h 39min • ★ 8.027/10 • France

Directed by: François Truffaut

Cast: Jean-Pierre Léaud, Claire Maurier, Albert Rémy, Georges Flamant, Patrick Auffay

For young Parisian boy Antoine Doinel, life is one difficult situation after another. Surrounded by inconsiderate adults, including his neglectful parents, Antoine spends his days with his best friend, Rene, trying to plan for a better life. When one of their schemes goes awry, Antoine ends up in trouble with the law, leading to even more conflicts with unsympathetic authority figures.

“The 400 Blows” is a classic French New Wave film directed by Francois Truffaut.

The film tells the story of Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Leaud), a troubled and rebellious adolescent who struggles with his troubled home life, problems at school, and an overall sense of alienation from the world around him.

The film is a poignant exploration of the difficulties faced by many young people as they navigate the challenges of growing up.

Through the character of Antoine, Truffaut offers a searing indictment of the institutional and societal factors that contribute to the marginalization of young people in modern society.

The film is visually stunning, with Truffaut employing a variety of experimental techniques to create a sense of disorientation and emotional intensity.

The use of handheld cameras, jump cuts, and naturalistic lighting all contribute to the film’s realistic and gritty tone.

- Jean-Pierre Leaud (Actor)

- François Truffaut (Director)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

The Nun (La réligieuse) (1966)

The Nun

The banned film by Jacques Rivette

1967 • 2h 20min • ★ 7.1/10 • France

Directed by: Jacques Rivette

Cast: Anna Karina, Liselotte Pulver, Micheline Presle, Francine Bergé, Francisco Rabal

In eighteenth-century France, a girl is forced against her will to take vows as a nun. Three mothers superior treat her in radically different ways, ranging from maternal concern, to sadistic persecution, to lesbian desire.

The Nun (La réligieuse) is a French drama film directed by Jacques Rivette and starring Anna Karina in the lead role.

The film is based on the novel of the same name by Denis Diderot and tells the story of a young woman named Suzanne who is forced by her family to become a nun.

As she struggles to adjust to the rigid rules and customs of the convent, Suzanne is subjected to various forms of abuse and mistreatment at the hands of the other nuns and the Mother Superior.

Despite her hardships, she remains determined to escape and live life on her own terms.

The Nun is a thought-provoking and powerful film that explores themes of oppression, abuse, and religious hypocrisy.

Rivette’s direction is both delicate and unflinching, capturing the oppressive atmosphere of the convent and the emotional turmoil of Suzanne’s journey.

Karina delivers a standout performance as Suzanne, portraying her with a mix of vulnerability and steely determination.

The supporting cast is also impressive, with several standout performances from the actresses portraying the other nuns.

- Photos

- ANNA KARINA (Actor)

- JACQUES RIVETTE (Director)

- Portuguese Brazilian (Subtitle)

Les bonnes femmes (1960)

The Good Girls

1960 • 1h 40min • ★ 6.3/10 • France

Directed by: Claude Chabrol

Cast: Bernadette Lafont, Clotilde Joano, Stéphane Audran, Lucile Saint-Simon, Pierre Bertin

Four Parisian women navigate the world of romance and daily life looking to fulfill their dreams.

“Les bonnes femmes” is a French film directed by Claude Chabrol that explores the lives of four young women working as shop assistants in Paris.

Despite their mundane jobs, each woman dreams of a better life, whether it be through love, fame or adventure.

The film follows the women as they navigate their everyday lives, from going out to dance clubs to dealing with lecherous male customers.

Their individual struggles and desires are contrasted with their shared experience of disappointment and disillusionment.

Chabrol’s direction is understated yet powerful, drawing attention to the quiet moments of everyday life and creating a sense of unease through the use of atmospheric sound and imagery.

The film is also notable for its feminist themes, as it portrays the women’s struggles against societal expectations and the limitations placed upon them.

- Factory sealed DVD

- Jean-Marie Arnoux, France Asselin, Stéphane Audran (Actors)

- Claude Chabrol (Director)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

Le bonheur (1965)

Happiness

Only a woman could dare to make this film.

1965 • 1h 20min • ★ 7.5/10 • France

Directed by: Agnès Varda

Cast: Jean-Claude Drouot, Claire Drouot, Olivier Drouot, Sandrine Drouot, Marie-France Boyer

A young husband and father, perfectly content with his life, falls in love with another woman.

“Le Bonheur” is a French film directed by Agnès Varda that tells the story of a happily married man named François who unexpectedly falls in love with another woman, and the subsequent consequences that follow.

François is a carpenter living in the suburbs of Paris with his wife Thérèse and their two children.

He is content with his life, but when he meets Émilie, a postal worker, he falls deeply in love with her. Despite feeling guilty,

François decides to pursue a relationship with Émilie, and they begin an affair. Initially, François feels that he can have both women in his life, but soon discovers that it is not that simple.

As the story unfolds, we see the devastating effects of François’ actions on his family and the people around him.

Varda masterfully depicts the complexities of human emotion and relationships, challenging the viewer to question their own beliefs about love and happiness.

“Le Bonheur” is a visually stunning film, with Varda’s use of bright colors and natural settings creating a serene and idyllic world that is shattered by François’ actions.

The film’s themes of love, morality, and the consequences of one’s actions are still relevant today, making it a timeless masterpiece of French cinema.

- Agnes Varda (Director)

- English (Subtitle)

- English (Publication Language)

- Audience Rating: NR (Not Rated)

La collectionneuse (1967)

La Collectionneuse

1967 • 1h 26min • ★ 6.903/10 • France

Directed by: Éric Rohmer

Cast: Patrick Bauchau, Haydée Politoff, Daniel Pommereulle, Alain Jouffroy, Mijanou Bardot

A bombastic, womanizing art dealer and his painter friend go to a seventeenth-century villa on the Riviera for a relaxing summer getaway. But their idyll is disturbed by the presence of the bohemian Haydée, accused of being a “collector” of men.

La Collectionneuse is a French New Wave film directed by Éric Rohmer.

It tells the story of Adrien, a young man who decides to spend his summer at a villa in the south of France.

His plans of solitude are interrupted when his friend Daniel arrives with his girlfriend, the free-spirited Haydée.

Adrien becomes infatuated with Haydée and begins to pursue her, but she is more interested in exploring her own desires and independence.

The film explores themes of love, desire, and freedom through its characters and their interactions.

It is a character-driven film that focuses on the internal struggles and emotional complexities of its protagonists.

Rohmer’s signature naturalistic style is present throughout the film, with long, unbroken shots and minimal editing.

La Collectionneuse received critical acclaim upon its release and is considered a classic of the French New Wave.

It is a thought-provoking and engaging film that offers a unique perspective on the complexities of relationships and the human experience.

- Spanish (Subtitle)

My Night at Maud’s (1969)

My Night at Maud's

1969 • 1h 50min • ★ 7.721/10 • France

Directed by: Éric Rohmer

Cast: Jean-Louis Trintignant, Françoise Fabian, Marie-Christine Barrault, Antoine Vitez, Léonide Kogan

The Catholic Jean-Louis runs into an old friend, the Marxist Vidal, in Clermont-Ferrand around Christmas. Vidal introduces Jean-Louis to the modestly libertine, recently divorced Maud and the three engage in conversation on religion, atheism, love, morality and Blaise Pascal's life and writings on philosophy, faith and mathematics. Jean-Louis ends up spending a night at Maud's. Jean-Louis' Catholic views on marriage, fidelity and obligation make his situation a dilemma, as he has already, at the very beginning of the film, proclaimed his love for a young woman whom, however, he has never yet spoken to.

“My Night at Maud’s” is a 1969 French film directed by Eric Rohmer.

The film is part of the “Six Moral Tales” series, a collection of films exploring themes of love, morality, and desire.

The story follows Jean-Louis, a devout Catholic and mathematician, who becomes infatuated with a woman he meets at church, Francoise. While out with friends, Jean-Louis runs into Maud, an old acquaintance, and spends the night at her apartment discussing philosophy, religion, and love.

The film is a dialogue-heavy piece, with much of the story taking place through conversations between the characters.

It explores complex philosophical ideas and questions of morality, particularly in regards to love and sex.

The performances in “My Night at Maud’s” are superb, with Jean-Louis Trintignant bringing a quiet intensity to his role as Jean-Louis.

The film’s pacing is deliberate, allowing the conversations between the characters to slowly unfold and reveal their innermost thoughts and desires.

- English (Subtitle)

- French (Publication Language)

- Audience Rating: Unrated (Not Rated)

Zazie dans le métro (1960)

Zazie dans le Métro

Liberté... Insanité... Hilarité!

1960 • 1h 33min • ★ 6.616/10 • France

Directed by: Louis Malle

Cast: Catherine Demongeot, Philippe Noiret, Hubert Deschamps, Carla Marlier, Annie Fratellini

A brash and precocious ten-year-old comes to Paris for a whirlwind weekend with her rakish uncle.

Zazie dans le métro is a surreal French New Wave film directed by Louis Malle and released in 1960.

The film is based on the novel by Raymond Queneau and tells the story of a young girl named Zazie who comes to Paris to visit her uncle.

However, her plans for adventure are thwarted when the Paris metro workers go on strike, trapping her in the city.

The film is a whimsical and playful exploration of Parisian life, seen through the eyes of a young girl. Zazie, played by Catherine Demongeot, is a mischievous and irreverent character who rebels against authority and challenges the status quo.

The film is a commentary on the social and political climate of France in the 1960s, and the generation gap that was widening between adults and youth.

Malle’s direction is experimental and daring, using jump cuts and unconventional camera angles to create a frenetic and energetic atmosphere.

The film’s colorful and vibrant cinematography captures the bustling streets of Paris, making it a visual feast for viewers.

Zazie dans le métro is a must-see for fans of the French New Wave and those who appreciate surreal and unconventional cinema.

Its playful and irreverent tone makes it a timeless classic that continues to captivate audiences to this day.

- Spanish (Subtitle)

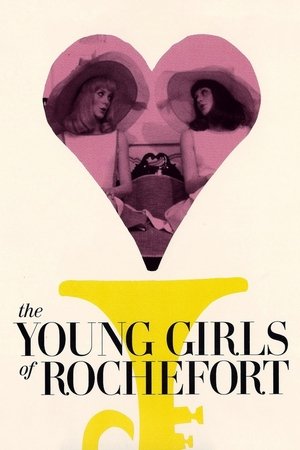

The Young Girls of Rochefort (Les Demoiselles de Rochefort) (1967)

The Young Girls of Rochefort

…They're singing and dancing in the streets.

1967 • 2h 6min • ★ 7.7/10 • France

Directed by: Jacques Demy

Cast: Catherine Deneuve, Françoise Dorléac, Jacques Perrin, Gene Kelly, Danielle Darrieux

Delphine and Solange are two sisters living in Rochefort. Delphine is a dancing teacher and Solange composes and teaches the piano. Maxence is a poet and a painter. He is doing his military service. Simon owns a music shop, he left Paris one month ago to come back where he fell in love 10 years ago. They are looking for love, looking for each other, without being aware that their ideal partner is very close...

“The Young Girls of Rochefort” is a French musical directed by Jacques Demy, with music by Michel Legrand.

The film takes place in the fictional town of Rochefort, where twin sisters Delphine and Solange are looking for love and adventure.

They meet a host of colorful characters, including a sailor, a musician, and a poet, all of whom are also searching for love.

The film is a vibrant and colorful celebration of life, love, and music.

The musical numbers are exuberant and joyful, with impressive choreography and catchy tunes.

The performances are top-notch, with Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac shining as the charismatic twin sisters.

But beneath the surface, the film also explores themes of identity, destiny, and the fleeting nature of happiness.

The characters all seem to be searching for something, whether it be love, artistic fulfillment, or a sense of purpose, but they all struggle with the transience of their desires.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=vZFK8svwtxA

- Catherine Deneuve, Françoise Dorléac, George Chakiris (Actors)

- English (Subtitle)

- Audience Rating: G (General Audience)

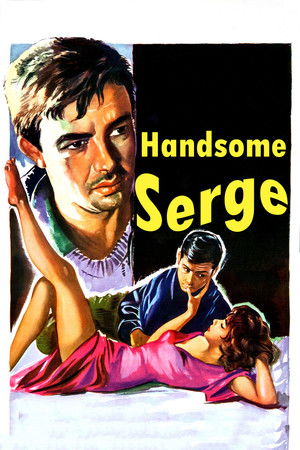

Le Beau Serge (1958)

Handsome Serge

1958 • 1h 38min • ★ 6.9/10 • France

Directed by: Claude Chabrol

Cast: Gérard Blain, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michèle Méritz, Bernadette Lafont, Edmond Beauchamp

After long absence, a man returns to his hometown only to find his best friend has become an alcoholic.

Le Beau Serge is the debut feature film from French director Claude Chabrol and is widely regarded as a cornerstone of the French New Wave movement.

The film follows François (Jean-Claude Brialy), a young man who returns to his hometown in rural France after a long absence to visit his childhood friend, Serge (Gérard Blain).

Upon his arrival, François discovers that his friend has become an alcoholic and is deeply unhappy with his life.

Despite François’ attempts to help him, Serge’s condition deteriorates, and François is forced to confront his own feelings of guilt and regret over their past.

Le Beau Serge is a strikingly raw and honest exploration of the complexity of human relationships and the struggle to find meaning in life.

Chabrol’s direction is both understated and powerful, conveying the film’s themes with a delicate touch.

The film is shot in black and white, and the bleak, desolate landscapes of rural France serve as a powerful metaphor for the characters’ emotional states.

Jean-Claude Brialy and Gérard Blain both deliver powerful performances as François and Serge, respectively, capturing the emotional turmoil and desperation of their characters.

The film’s score, composed by Pierre Jansen, is haunting and evocative, adding to the film’s melancholic and introspective tone.

- Factory sealed DVD

- Gerard Blain, Jean-Claude Brialy, Michele Meritz (Actors)

- Claude Chabrol (Director)

- English (Subtitle)

- English (Publication Language)

What Are The Characteristics Of French New Wave

The French New Wave, or ‘Nouvelle Vague’, ushered in a fresh cinematic language marked by distinctive stylistic elements that I’ve come to admire.

One of these standout elements is the use of location shooting, with directors taking cameras out of the studios and into the streets. This not only reduced production costs but also added a layer of realism to storytelling.

In addition, the movement was known for its innovative use of the camera. Handheld shooting became a signature of New Wave films, giving them a sense of immediacy and dynamism that previous films lacked.

Jump cuts were another hallmark, a technique where successive shots of the same subject are taken from angles that vary only slightly. This created a disconcerting, yet attention-grabbing effect, which is now a common sight in modern cinema.

The directors of the French New Wave also had a unique approach to narrative structure. Rather than adhering to a conventional plot-driven sequence, many New Wave films were characterized by loose, often ambiguous narrative arcs. These stories were more about capturing moments or moods rather than telling a linear tale.

Character portrayal was equally groundbreaking. Complex, flawed protagonists became the norm, veering away from the stereotypical heroes and villains. The dialogue in these films, often improvised, added another layer of authenticity to the characters and their interactions.

Moreover, editing played a pivotal role in establishing tone and pacing. Fast-paced editing was often juxtaposed with prolonged shots, making viewers more aware of the filmmaking process itself. This self-reflexive technique served to remind the audience that they were indeed watching a film.

To truly appreciate the stylistic elements of this era, one must watch the films and see how directors like Truffaut and Godard used these techniques to challenge and reinvent cinematic norms.

These elements didn’t just influence French cinema; they left an indelible imprint on the global film industry.

The following are some characteristics that you might find in a film from this movement:

- hand-held camera,

- jump cuts,

- point-of-view shots,

- offscreen space or sound used to imply something happening elsewhere on the screen (usually out of view),

- fast cutting between various scenes or shots that show what different characters are doing during the same time period (often done without regard for continuity),

- sudden changes from silence to loud music or vice versa,

- unusual angles,

- A rebellious and/or youthful streak.

How Did The French New Wave Movement Originate

Before diving deeper into the French New Wave or Nouvelle Vague, it’s essential to understand its roots.

Born in the post-World War II era, this movement took shape in the late 1950s and was, in part, a response to the social and political turmoil that France experienced.

The nation was grappling with the ramifications of the war and a new generation sought to break away from the constraints of traditional French society.

The film industry itself was undergoing significant shifts. Italian Neorealism had already introduced a fresh, realistic lens on society which resonated with the young up-and-comers in France.

They drew inspiration from this movement, as it focused on ordinary people and everyday life, devoid of the glamorous veneer typical of mainstream cinema.

Economic factors also played a significant role. The cost of film production dropped significantly, enabling these pioneering directors to experiment without the fear of financial ruin.

Lightweight cameras and advances in technology allowed for greater flexibility in shooting—they could now take their cameras to the streets, capturing life as it was lived by the youth of Paris and beyond.

Cinema attendance in France was at an all-time high post-World War II. Film became a critical medium for both entertainment and cultural expression.

Despite the popularity of cinema, many young intellectuals criticized mainstream French films for their rigidity and lack of innovation.

The Cahiers du Cinema, a prominent film magazine, became a mouthpiece for these criticisms, with contributors such as François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard openly challenging the status quo.

Truffaut coined the term “auteur” theory, insisting that a director’s films should reflect a personal signature, akin to the author of a novel.

This concept was groundbreaking, assuring that each film was a vessel for the director’s own vision and philosophies. The stage was set for a revolution, and the Nouvelle Vague was the banner under which these new auteurs would assemble.

These directors are credited with breaking down many barriers within filmmaking, such as those between fiction and documentary filmmaking and between cinema and television.

The new wave style is often thought to have been influenced by Italian Neorealism from 1945 to 1954 because they both share similar styles.

However, these two movements have different origin stories so they are not mutually exclusive or inclusive of one another.

International Popularity Of French New Wave

As we’ve covered, the French New Wave film movement was distinguished by its use of jump cuts, hand-held camera work, natural lighting, and filming on location.

The films were also noted for their youthful energy and rebelliousness.

The popularity of this film genre can be seen today with many new filmmakers in America adopting these techniques.

French New Wave is a movement within the French film industry occurring from about 1959 to 1964.

It was an era in which they experimented with lighter and more informal storytelling methods, like handheld cameras, jump cuts, fast cutting, location shooting, and improvisation.

The result was a new kind of cinema that rejected many of the conventional rules of Hollywood filmmaking and relied on experimentation.

This style became popular around the world for its use of naturalistic dialogue and casual settings.

As a result, it has been influential on generations of filmmakers including those who made modern-day classics such as Pulp Fiction or Raging Bull – Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese, respectively.

How The French New Wave Changed Cinema

The French New Wave, known as “Nouvelle Vague”, didn’t just revolutionize French cinema; it rippled across ponds to impact global filmmaking in profound ways.

Directors and cinephiles worldwide drew inspiration from the movement’s signature freedom of expression and experimental approach.

One of the first and most palpable areas of influence was narrative structure. The New Wave introduced a form of storytelling that felt more authentic, sometimes bordering on the autobiographical.

International filmmakers started adopting these raw, character-driven narratives that often defied classic three-act structures.

Movies began to mirror the unpredictability and complexity of real life, thanks to the groundwork laid by Truffaut, Godard, and their peers.

Technique and Style were also heavily influenced. The Nouvelle Vague’s penchant for on-location shooting, handheld camera work, and natural lighting sparked a stylistic overhaul far from the polished look of Hollywood’s golden age.

This guerrilla filmmaking approach not only democratized the film production process but also birthed movements such as Cinéma Vérité and Italian Neorealism, both of which owe their ethos to the French New Wave.

Perhaps one of the most crucial areas influenced was editing. The movement’s radical approach to cutting—jump cuts and non-linear sequences—encouraged editors to view their craft as an instrument of artistry rather than mere storytelling mechanics.

This led to a global rethinking of how film rhythm and pace could manipulate audience emotions, a technique now ubiquitous in the editing suites of the film industry.

Additionally, the New Wave’s influence seeped into film schools and education systems, changing how future filmmakers were taught the craft of cinema.

Film theory and critique, heavily advocated by New Wave directors, became staples in film curricula around the world.

This intellectual approach to filmmaking cultivated a generation of directors who valued cinema as a form of dialogue between the creator and the audience.

The wider new wave was an artistic movement in France and other parts of Europe, which changed the way cinema was made: it challenged traditional Hollywood standards by using handheld cameras, natural lighting, and sound recording on location.

The filmmakers wanted audiences to feel as if they were part of the story rather than looking at it from afar.

The filmmakers also used unconventional editing techniques for their time that created a frenetic style with jump cuts and quick edits known as “jump-in” or “cut-in”.

From these techniques came what we know now as modern cinematography. These techniques can be seen today in films such as Mean Streets (1973) by Martin Scorsese and the work of Quentin Tarantino.

It’s impossible to ignore the effect French New Wave had on genre films. The movement’s audacity pushed boundaries and blended genres in innovative ways, leading international filmmakers to mix conventions and experiment freely with film tropes.

From the Western revivals to modern-day action flicks, the seeds of genre-blending planted by the Nouvelle Vague persist in today’s cinema.

The Legacy of French New Wave in Contemporary Cinema

Filmmakers across the globe drew inspiration from this movement’s defiance of classical storytelling and pioneering techniques. Innovative Storytelling became a hallmark that so many auteurs aspired to replicate.

The movement imparted to them a spirit of rebellion against rigid norms, leading to the creation of films that were unafraid to showcase the director’s personal vision and social commentary.

Moreover, the use of handheld cameras and natural lighting has become commonplace in the industry, offering a more intimate and realistic approach to filmmaking.

This technological democratization means that shooting on location, once a groundbreaking New Wave approach, is now an effective industry standard for adding authenticity to a narrative.

Editing Techniques introduced by the New Wave have significantly altered the pace and rhythm of films. Quick cuts and jump cuts, once avant-garde, are now essential components in the editor’s toolkit, often used to create a sense of urgency or to convey a character’s inner turmoil.

The New Wave’s influence extends to Film Education as well. Many modern film programs incorporate New Wave films and their methodologies into their curriculum.

This fosters an environment where film theory and criticism go hand in hand with practical filmmaking, encouraging students to challenge the status quo just as the French New Wave directors did.

In terms of Genre Films, the New Wave’s impact is palpable. It demonstrated that genres could be deconstructed and reassembled in ways that blurred lines and challenged audiences’ expectations.

This approach spawned genre-bending works that combine elements of noir, romance, and science fiction, to name a few, crafting unique cinematic experiences that defy conventional categorization.

The New Wave’s storytelling methods and character-driven focus continue to resonate with audiences who prefer complex narratives over formulaic scripts.

It’s clear: the New Wave spirit of subverting norms and embracing artistic expression still pulsates through the heart of modern cinema today.

Criticism and Analysis of French New Wave Films

As I moved deeper into the intricacies of French New Wave films, I’m struck by the myriad of critical viewpoints they’ve elicited. Film critics and scholars have long debated the artistic merits and drawbacks of these pioneering works.

On one hand, the New Wave is lauded for revolutionizing cinematic conventions and introducing techniques that fostered a more personal connection between the viewer and the film.

One critical analysis of French New Wave centers on the movement’s detachment from traditional storytelling.

Proponents argue that this breakaway helped to elevate film to a more artistic and experimental level, one where directors like Truffaut and Godard could express personal vision free from the constraints of classic cinema.

Their disregard for cinematic norms is seen not as a lack of conformity but rather a bold artistic statement.

However, not all feedback has been positive. Some critics argue that the movement’s spontaneous and often improvisational nature led to a lack of cohesion and polish in the final films.

Traditionalists, in particular, suggest that the lack of a tightly scripted narrative can leave the audience feeling disjointed and unengaged.

They see the handheld camera work—not the hallmark of professionalism—as potentially disorienting and cite this as a pitfall of the movement’s quest for realism and intimacy.

Despite these criticisms, it’s clear that French New Wave has left an indelible mark on filmmaking.

Film studies often include an in-depth analysis of New Wave techniques as a critical part of the curriculum, bringing scholarly attention to its editorial boldness and narrative innovations.

The academic discussions generated by these films attest to their lasting impact and importance in the cinematic canon, continually prompting reevaluation and reinterpretation among the film community.

Whether loved or challenged, the French New Wave represents a key moment in film history.

French New Wave and the Art of Storytelling

One can’t help but notice its profound influence on the art of storytelling. Directors of this movement disrupted the traditional narrative flow that audiences had come to expect from mainstream films.

They traded in tightly woven plots for a more fragmented and often ambiguous narrative structure.

This new approach allowed for deeper character exploration and a narrative style that more closely mirrored the inconsistencies and unpredictability of real life.

The hallmark of French New Wave storytelling was its non-linear approach. Films frequently employed flashbacks, ellipses, and jump cuts that challenged viewers to piece together the story, engaging them in a more active viewing experience.

They often had protagonists who were complex and flawed, which added a layer of realism absent in the archetypal heroes of classic Hollywood cinema.

This movement also introduced the concept of the “auteur” to filmmaking. Directors like Truffaut and Godard placed personal vision and style above all else, becoming the storytellers themselves rather than just directors of a script.

My interpretation of their work suggests a belief that the director’s role is akin to that of a writer, with the camera serving as their pen.

In terms of dialogue, the New Wave penchant for improvised conversations brought a natural and dynamic quality to the films.

The spoken word became as important as the visual elements, showcasing the filmmakers’ appreciation for the subtleties and nuances of everyday communication.

The French New Wave’s storytelling was not just about what was told, but how it was told. Innovative editing techniques such as the use of jump cuts not only served to condense the narrative but also imparted a rhythm and energy that echoed the tumultuousness of the characters’ lives.

By interweaving documentary realism with artful cinematography, the New Wave directors blurred the lines between truth and fiction, further enveloping the audience in their narrative web.

In examining the narrative techniques of the French New Wave, it’s clear that the movement’s storytelling was a reflection of a post-war generation yearning for authenticity and self-expression.

Learning from French New Wave: Tips for Filmmakers

The French New Wave remains an inexhaustible reservoir of inspiration for filmmakers. As I continue to mine this rich vein, I’ve gathered some pivotal tips that are as relevant today as they were at the movement’s inception.

Be innovative with your narrative

Don’t feel confined to linear storytelling. Non-linear plots, abrupt changes, and open endings can captivate the audience by creating an interactive viewing experience.

Challenge viewers to piece the story together, to actively engage with the narrative rather than passively consume it.

Use your limitations to your advantage

Many New Wave filmmakers worked with limited budgets and resources. They turned these constraints into opportunities for creativity.

If you’re faced with budgetary restrictions, consider more affordable shooting locations or smaller, but more dedicated, crews.

Embrace on-location shoots

The allure of natural settings brought a palpable authenticity to French New Wave films. This unconstrained environment can enhance the realness of a scene.

Don’t shy away from using the world outside the studio—embrace it to add depth to your storytelling.

Prioritize personal style

Each New Wave director’s voice was distinct. Find and refine your unique voice and vision. Your personal storytelling flair is valuable; let it shape your films and differentiate them from the rest.

Experiment with editing

Be bold with your cuts. Juxtapose shots for visual impact or to create unique rhythms within the narrative. Leap out of continuity editing into realms that challenge traditional forms.

Rethink character construction

Complex, multifaceted characters became hallmarks of New Wave films. Your characters should feel real—flesh them out with backstories, quirks, and contradictions. Viewers often latch onto characters who embody genuine human traits and complexities.

Break rules, but know why you’re breaking them

The New Wave was revolutionary because the directors understood the conventions they were defying. If you decide to bend or break a rule, do so with a clear understanding of the effect you’re aiming to achieve.

By implementing these fundamental elements, the spirit of the French New Wave can live on in modern filmmaking, continuing to challenge and to charm audiences across the globe.

What Is French New Wave – Wrap Up

The French New Wave remains a touchstone of cinematic innovation, its legacy as vibrant today as it was in the 1950s and 60s.

This movement spawned such icons as Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette.

The films often had creative techniques not seen before at the time like jump cuts and camera angles to make viewers feel more connected with what they are seeing on screen.

We’ve seen firsthand how its bold techniques and personal storytelling continue to resonate, influencing contemporary filmmakers who dare to push boundaries.

It’s a testament to the movement’s enduring relevance that its principles—embracing limitations, prioritizing personal style, and breaking rules with purpose—are still vital in film education and practice.

The New Wave’s spirit, with its blend of realism and artful cinematography, challenges us to rethink the art of storytelling, ensuring that the movement’s ripples are felt in the ever-evolving landscape of cinema.

We hope you’ve enjoyed our guide to the French New Wave. What are your favorite French New Wave films? Let us know in the comments below.

French New Wave – Frequently Asked Questions

Who were the key directors of the French New Wave movement?

François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Éric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, and Agnès Varda are recognized as key directors of the French New Wave movement.

What are some seminal works of the French New Wave?

“The 400 Blows” by François Truffaut and “Breathless” by Jean-Luc Godard are seminal works that exemplify the innovative film techniques and storytelling of the French New Wave.

What are the distinctive stylistic elements of French New Wave cinema?

Distinctive elements include location shooting, innovative camera techniques, loose narrative structures, complex protagonists, improvised dialogue, and unique editing styles.

How did the French New Wave impact global filmmaking?

It inspired filmmakers worldwide to adopt more authentic narratives, experiment with new techniques, rethink editing, incorporate film theory into education, and blend genres in innovative ways.

What criticisms are associated with French New Wave films?

Critics argue that French New Wave films often lack traditional storytelling cohesion and can appear detached, although many praise the movement for revolutionizing cinematic conventions.

How has the French New Wave influenced the art of storytelling in cinema?

It disrupted traditional narrative flow with non-linear structures, introduced complex protagonists and improvised dialogue, and used innovative editing techniques to create a more personal cinema.

What tips can modern filmmakers take from the French New Wave?

Modern filmmakers can learn to be innovative with narrative, embrace limitations, utilize on-location shooting, prioritize personal style, experiment with editing, rethink characters, and break rules intentionally.

Ready to learn about more Film History & Film Movements?

Matt Crawford

Related posts

2 Comments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

![Umbrellas Of Cherbourg (50th Anniversary Edition) [1964] [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51x2b7mMU8L.jpg)

![Paris Belongs to Us (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41ojRnfa9KL.jpg)

![Shoot the Piano Player (1960) ( Tirez sur le pianiste ) [ NON-USA FORMAT, Blu-Ray, Reg.B Import - United Kingdom ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51lLwBvyV5L.jpg)

![Last Year at Marienbad (1961) ( L'Année dernière à Marienbad ) ( L'Anno scorso a Marienbad ) [ Blu-Ray, Reg.A/B/C Import - France ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/517amHopEmS.jpg)

![La Jetee (1962) / Sans Soleil (1983) - 1 disc (Criterion Collection) UK only [Blu-ray] [2019]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51ZDcydnWLL.jpg)

![Jules & Jim [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51-VZaND3VL.jpg)

![Pierrot le fou (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41BHZQFcZDL.jpg)

![Le Mepris (The Studio Canal Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Xmjkg+4mL.jpg)

![Hiroshima mon amour [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/6154IbvY6uL.jpg)

![5 O 'Clock from to 7 O 'Clock Cleo [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51rwvcryfHL.jpg)

![The 400 Blows (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51UH-mDrY1L.jpg)

![La Religieuse [ The Nun ] [ Jacques Rivette ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51ACz4YCq3L.jpg)

![Four by Agnes Varda (La Pointe Courte / Cleo from 5 to 7 / Le bonheur / Vagabond) (The Criterion Collection) [DVD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41sHLrBEHRL.jpg)

![My Night with Maud ( Ma nuit chez Maud ) ( Six Moral Tales III: My Night at Maud's ) (Blu-Ray & DVD Combo) [ NON-USA FORMAT, Blu-Ray, Reg.B Import - France ]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/5174tzCnnEL.jpg)

![The Young Girls of Rochefort (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51ez7FZvW0L.jpg)

![Le Beau Serge (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41C9hUWCzaL.jpg)

Hello! I am trying to credit the author of this article on the French New Wave but I can’t seem to find the full name or information on who wrote this. Please let me know who you are so I can give you your credit.

Thanks, Suzanne.

Matt Crawford.